Range of forces impacts pork packer industry

What is industry capacity when viewed through a historical lens? Short answer — it is up, way up.

October 3, 2018

The hog industry is living in interesting times as producers raise more pigs, and packers keep ramping up production. As fall approaches, the industry is on target to raise processing capacity to new highs — nearing 500,000 pigs per day.

“I’m not a number-cruncher, but we’ve got record-large numbers of pigs — but we’re not having shackle space issues,” notes Dennis Smith, livestock commodity broker, Archer Financial Services. He adds that this is the third year in a row for record production with no constraints from packers.

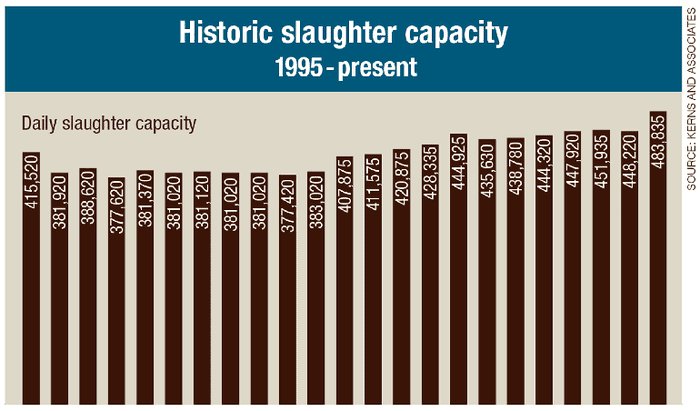

Steve Meyer, Kerns and Associates, takes his annual look at current packer capacity, with the latest numbers. But what is industry capacity when viewed through a historical lens? Short answer — it is up, way up.

The accompanying chart from Kerns and Associates shows how daily capacity has risen since 1995. It’s a picture of an industry that’s been growing to meet rising global demand.

“We’re going to kill more hogs than we’ve ever killed before,” says David Williams, senior vice president, Informa Economics IEG. “I guess the range is about 473,000 to 480,000 per day, and then there’s the Saturday question.”

This daily slaughter is the current level from a steady rise that’s been going on since 1995, when capacity was less than 370,000 per day.

The “Saturday question” Williams refers to is the capacity the industry could hit for that sixth day of the week. He’s estimating the number at about a quarter of a million now, with the potential to rise to more than 300,000. “That’s about the capacity, and there’s a lot of debate about that,” he says.

A tighter labor market puts pressure on how hard packers push for that sixth day of production. “If packers push workers for a kill on Saturday, they might not show up for work on Monday,” Williams says.

Historically tight labor is visible everywhere you turn, from “We’re hiring” signs at the local convenience store to demand from major manufacturers like John Deere for skilled workers. That can limit management flexibility in “pushing” production. Yet the industry continues to expand.

One flex area is the addition of a second shift at the Seaboard Triumph plant in Sioux City, Iowa, which is in the works for October. However, Williams says that could happen later. Concern about labor shortages is making a difference in plant expansion, though he adds the industry can work through that challenge. He notes that the facility isn’t running at full capacity with a single shift.

Williams says there is the view that packing capacity is already over 480,000, but, he notes, “I’ve spent too much time in a packing plant, and that number is if everyone in the industry is working perfectly at capacity.”

External factors weigh in

A new shift at the Seaboard Triumph facility could bump production up another 10,000 per day, and Williams is also looking at the Prestage plant in Wright County, Iowa, coming online by 2019 for another 10,000 per day. “The industry is ramping up to do 500,000 hogs per day, but we’re not there yet,” he says.

Some observers, like Smith, see trouble ahead, with a tighter labor pool and a potential truck shortage. Williams counters that there are enough trucks, though they’re going to cost more money. In addition, the industry can work to buy its way out of the labor problem.

“I would tell you that right now, the hourly wages are up 50 cents to $1.50 to maintain the workforce, and on average they’re making $17 per hour. Five years ago that number was closer to $12.50,” Williams adds.

He also points to Tyson and JBS, which are currently hiring people with a two-year degree — or no degree, but the right experience — for some in-plant work, and they’re getting $25 to $27 per hour and a $10,000 sign-on bonus. “But that’s for multiple proteins, including chicken, beef and pork, for their plants,” he notes.

Producers have been doing their part to meet growing global demand for pork. Yet as demand softens due to trade issues, some look back to the price collapse of the late 1990s and worry about what might happen. “This is not the 1990s,” Williams adds. “The last time we did hit capacity limits, I was very young in my career; the market went to 7 cents.”

He explains a price drop that big is unlikely this time around, noting that 40% of the industry is integrated today, versus about 5% to 10% back then. “There’s a lot more incentive not to drive the price down to 7 cents,” he says.

Given rising integration, packers can control the flow of animals into processing. There’s already evidence that processors are slowing pig deliveries by up to a week, which may prolong price weakness, but won’t grind prices down to those historically low levels so many remember.

When viewing packer numbers, and capacity, external factors can weigh in. Meyer notes that earlier this year, global exports were a key part of the market. Trade pressures created by recent tariff battles are impacting demand.

Meyer points out that the pork industry always has slack capacity during summer months, but has seen high levels of capacity utilization in the fourth quarter of most recent years. In fact, 2014 was the only year since 2010 in which throughput during the year’s highest week was significantly below capacity — and that shortfall was caused by porcine epidemic diarrhea virus. Generally, high capacity use in recent years led to higher gross margins and strong packer profits. Those profits are the primary driver for the recent expansion.

Add in the changing nature of production, with fewer, but larger, producers and a higher level of integration, and market dynamics for the industry have changed. By fall 2019, total capacity could top 500,000 pigs per day. Historically, that’s a new level; and for the industry, it brings new market factors to consider.

“This is a really strange market,” comments Smith. “It’s so bearish now, but what I find difficult about the market is that it is so streaky.” He’s seeing prolonged periods where prices will slide, followed by several days with prices rising.

For producers working to hedge production, that can be a challenge. Comments Smith: “The streakiness is difficult to deal with.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like