’19 Pork Masters: Go with your strengths

Wakefield Pork Inc. relies on strengths of employees, contract growers for proper pig care.

The Langhorst family behind Wakefield Pork knows how to take care of pigs, and they have known enough to stick to their strengths. “We don’t own feed mills or trucks,” says Lincoln Langhorst, general manager for Wakefield Pork Inc., based in Gaylord, Minn.

Rather than spread their staff and resources thin by operating company-owned feed mills and managing a line of feed and hog trucks, the WPI management team has instead teamed up with feed mills and trucking firms throughout the company’s footprint — which stretches from Little Falls, Minn., on the north to Le Mars, Iowa, on the south; and the South Dakota border on the west to Owatonna, Minn., on the east.

“We work with people who treat the pig like it’s their own,” Steve Langhorst says.

That dedication to the health of their swine herd has made the Langhorst family and Wakefield Pork Inc., one of the 2019 Masters of the Pork Industry.

Starting small

Steve Langhorst was raised on a hog and crop farm near Gaylord, in south-central Minnesota, while Mary grew up in Gaylord. Mary and Steve married in 1977, and along with Steve’s dad, they started farming small — with 30 sows, 13 crates and a few acres of row crops. This made Steve the fourth generation to farm on the “home farm.”

In 1978, they began working with Tim Loula, a veterinarian at the Swine Vet Center in St. Peter, Minn., starting a trend of “surrounding ourselves with very good people,” Steve says.

Aligning with good people has been a strategy for the Langhorst family, and the beginning and growth of WPI. Steve and Mary had been looking to build a sow unit — but where to build it? In 1991, they paired with Chuck Peters, a fellow farmer from Nicollet, Minn., and went together to lease a farm in Stearns County, Minn.

“Langhorst-Peters was too much for the name of the farm, and we didn’t really want our names on it because it wasn’t about us,” Steve says. The farm was in Wakefield Township, near Richmond; thus, the name of Wakefield Pork was born. With that first sow farm about 80 miles away from the Gaylord hub, they would take turns making site visits each week to check up on production.

“We sold 200-head lots of feeder pigs, which was considered large groups at the time,” Steve says. Wakefield Pork then started working with contract growers, “and we kept evolving and growing from there,” he says. The company now works with 250 contract growers, who own the barns while Wakefield provides the pigs, feed and veterinary care.

Today, Wakefield Pork cares for 55,000 sows and markets more than 1.4 million hogs each year. That growth has been gradual — and not for the sake of growth. “We never set out to be the biggest,” says Lincoln, son of Steve and Mary. “We want to be the best.”

Steve says the daily drive is for good production. “Just to have numbers doesn’t make success,” he says. “We try to be futuristic and look down the road. We want to stay up with the times and see where there is potential to make the system better. … Our decision-making is based on our culture. … The risk-reward has never been greater than it is now.”

WPI has grown by taking advantage of opportunities as they arose and by working with good people, Steve says.

Mary has always been an integral part of the operation, even when she worked in a bank in Lafayette, Minn., in the early years. “I would do PigCHAMP [computerized health and management program, software for pork production management] in the mornings, and then work at the bank. … Our kids lived our business at the kitchen table,” she says.

In addition to Lincoln, Steve and Mary also have a daughter, Jackie, who works for Cargill and lives in Stillwater, Minn.

Mary quit the bank in 1993 to concentrate more on the hog business. Her role has evolved over time, from handling PigCHAMP records and marketing to handling human resources, which is what she went to college for. She now has the dual title of chief operating officer and human resources director. She relinquished the marketing duties to Lincoln when he returned to the family operation in 2008. As the hog production has grown over the years, so has the human side of the operation, growing from one employee to 275.

The Langhorst family and WPI management know the value of good employees, and the family wishes to stay connected with their employees — as evidenced by Mary doing annual reviews for each of the 275 employees.

“We take a bottom-up approach,” Steve says. “We listen to what the people in the barns have to say. They are there with the pigs every day. … The money is made in the barns.”

What’s fun gets done

Obviously, relying on the good work of employees alone doesn’t guarantee results. Record-keeping and tracking are important to gauge the success of the operation as a whole. With that in mind, 16 years ago, Mary initiated “NASPIG,” a sow farm competition that runs the duration of the NASCAR racing circuit season.

Points are tallied weekly for sow farms on eight different categories of production records. A display case in the lobby of WPI’s main office on the east edge of Gaylord has a miniature racetrack, and cars and banners for the top “performers” for each week. Throughout the NASPIG season, sow farm managers can get a quick glance at how they fared each week, each quarter and overall for the season.

Keeping with the competitive spirit, the leaderboard shows the points that each team is behind the leader, as well as the points by which each team trails the next position.

“It’s fun for them [sow farm managers] to take a look at and see how they can get better, to catch the next team that’s ahead of them,” Steve says.

“This was built for the newcomers, so they could see what is important in our business, and what we would be looking at on a regular basis,” Mary says. “But, it’s become a popular way for everyone to be able to see how all the teams are doing. It gets competitive, and they have fun doing it. As I always say, ‘What’s fun gets done.’”

NASPIG gives points for sow farms on metrics such as farrow rate, total born, prewean mortality, pigs weaned per sow, etc. In addition to typical production metrics, sow farm managers can also receive bonus points by turning in paperwork in a timely manner, or by illustrating one of the We Care principles.

“They also can gain points just by turning in a report on time,” Mary says, stressing the importance of following proper protocol.

Lincoln says the family learned from the veterinarians at Swine Vet Center that being challenged can improve the scope of the business. “Our vets challenged us early on,” he says, “and we challenge our employees to continue to improve. … Any metric that we can measure, we compete on.”

Health matters

Without the pigs, there would be no WPI and there would be no need for a NASPIG competition. Maintaining the health of the company’s herd is of the utmost importance.

“We learned that pig health is important early on,” Steve says. He credits Paul Yeske, a veterinarian at Swine Vet Center with “bringing up the idea of eradicating myco [Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae] in our pigs. We weren’t sure it could be done, but with his help we are now 100% myco-free companywide.”

In 2008, as an added health measure, the company started filtering the sow farms, and now 85% of the company’s sow farms are filtered. “Health comes first,” Lincoln says. “It’s fun to see what a healthy pig can do. The sow has doubled its productivity during Dad’s time.”

Steve feels the industry needs to take more credit for the advancements that have been made, from the breeding stock and genetics to good feed and good care for the animals in the barns.

As mentioned before, there are no WPI feed mills, nor is there a WPI trucking line. Rather, the company works with feed mills and trucking firms throughout the Wakefield geographic footprint. WPI management vets the qualifications of the feed mills and the trucking firms. “They all know the standards that we operate under,” Steve says.

Big family

Even though Steve, Mary and Lincoln are the only Langhorst family members working for WPI, the trio looks at all employees as family. “Everyone here has worked their way up,” Steve says, with Lincoln adding, “We have all had a pressure washer wand in our hands at some time.”

Workers’ employment longevity is evident in the fact that the management team averages a tenure of 17 years with the company. “Our culture is family,” Mary stresses, and this family appears to stick together — or at least return.

After graduating from Sibley East High School in Gaylord, Lincoln attended Augsburg University in Minneapolis, where he played football and majored in business management. During high school, he envisioned taking over the crop side of the family’s operation, but he didn’t move home right away.

After college graduation in 2003, Lincoln took a logistics job with Dart Transit Co., a trucking company based in Eagan, a southern suburb of the Twin Cities. “I was once told it’s good to get experience on someone else’s dime, so when you screw up it’s not on your own,” he says, but adding it was all the time “with the quest to get back home, but never 100% sure.” A mentor at Dart encouraged the young Langhorst to pursue his master’s degree, which he did on nights and weekends while at Dart.

When he worked on real-life projects for his master’s, he caught himself often referring back to Wakefield, “and it started to click, thinking, ‘Why am I going to earn this degree and use it for someone else. Why not use this education back at home?” he says, adding it was a good time to get back to the farm and the rural life, as he was preparing to get married. His wife, Jackie, was also from a small town.

Timing can be a double-edged sword, as his impending marriage also coincided with $7.50 corn and swine flu. “Probably a unique time to come back just with the economic challenges we were facing, but I kind of thought that if there’s any better time to learn, it’s to learn when it’s bad,” he says of 2008, when he joined the family enterprise. He is the fifth generation to farm in the family. “You learn to be disciplined,” he says.

Upon his return he took over sales, marketing and trucking from his mother. At this point, Chuck Peters was contemplating retirement, so Lincoln shadowed him for a couple of years in his duties, involving risk management, hedging and command to work with the Chicago Board of Trade. Once Peters retired, Lincoln stepped into those duties, “as well as any other duties that come up. No two days are ever the same here at Wakefield, that’s for sure.”

Atmosphere of respect

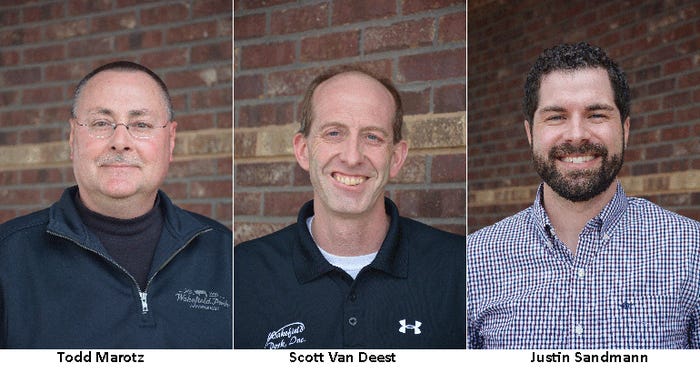

Lincoln is not the only one to return to the Langhorst-Wakefield family. Scott Van Deest started working with Steve Langhorst when Van Deest was a junior in high school and then moved to Colorado for four years. “When I moved back, I went to Steve and Mary to see if they had a job available for me again,” he says. They did, and he has been with the family ever since. Now a sow farm manager, he has been with the Langhorsts for 25 years. He also helps with the crop side.

“I think respect on both ends is a big thing,” Van Deest says of his reason to come back and to stay for as long as he has. “He [Steve] instills a lot of trust in you. I remember back in the day, when Steve would come into the barns and take the time to show you the way that he would like things to be done.”

The trust that Steve Langhorst has shown Van Deest has trickled down to the 10 full-time employees the sow farm manager has under his watch in his barn. “I enjoy the sow farm part of it, and always try to build a good team with the guidance of Steve and Mary and my supervisors. … I think we’ve always been one of the top-producing units, but that all comes from learning over the years from Steve and Mary, and all the decisions being made. You don’t have to make them on your own; we can talk through it. Let’s make the best decision we can for the company or the sow farm. … If something happens we’re going to work through it together, so the mistake is not going to happen again.”

Van Deest saw the strength of Steve Langhorst — and maybe what exemplifies a “Master” — when the company experienced a downturn. “He never once asked any farm that ‘We have to cut this or take shortcuts here because the markets are crap,’” Van Deest says. “That’s one thing that was never talked about when they had a bad month or more, because Steve knew if we cut here, it’s going to end up hurting us in the long run.”

Todd Marotz, head of production, was drawn to WPI by seeing from the outside how the operation has been structured. He works with genetics and construction as well as environmental issues within the company and has been with WPI for a little more than 12 years.

“I find it quite unique, with a company of this size, how the family is as involved in the day-to-day operations — whether it be with the internal multiplication, boar stud, contract growers, and just all the pieces of that — how involved they are,” he says.

Reaching out

Though hog production is the core of the WPI business, the Langhorsts believe it is important to recognize that they are operating within a community.

“They take a real connection with the employees,” Marotz says. “We like to think we have a relationship with everybody that is similar to a family.”

Community is a part of the We Care principles, which Mary actually had a hand in helping develop with the National Pork Board, and the WPI team believes in reaching out to those in the communities in the company’s footprint.

WPI operates under five core values, as posted on the company’s website:

Principled. We raise our pigs using the utmost ethical, innovative and nutritious methods.

Forward-thinking. We focus on continuous improvement and are always looking for opportunities to listen and change.

Dynamic and united. Our team members bring their own best practices, experiences and knowledge. We encourage the sharing of ideas because when shared, everyone’s game is raised.

Steady and stable. WPI is persistent in our pursuit of growth and sustainability, even in the most challenging economies.

From our family to yours. Each of our employees and growers play an important part in bringing dinner to the family table. We are proud consumers of our own product.

“They always go out of their way for people,” says Justin Sandmann, WPI’s chief financial officer since 2007. “Steve and Mary do things that as a boss they wouldn’t have to do, but they do. … They always go out of their way to treat employees as more than just a number.”

Sandmann says in addition to the Langhorsts reaching out to lend a helping hand, he says they are also good at rewarding employees for the work they’ve done, and not necessarily just monetarily. “They want to reward you for a job well done.”

Reaching out to those in need touched Sandmann closer, perhaps, than some of his coworkers. As part of a leadership program, Mary had employees write an essay about a time when they had made a difference in somebody else’s life.

“I had trouble coming up with anything grandiose,” he says. “I have two small children, so I hope I make a difference in their lives, but I didn’t have that one thing that I could point to. So, I wrote that and turned it in and told Mary that I think I failed here.”

Not more than a month later, he was sitting in an early childhood family education class with his son when he heard that one of his son’s classmates needed a kidney.

“When the mother was telling me about this, one of the first things that popped into my head was, ‘Here’s my chance to write Mary and say I made a difference in this boy’s life.’ I like to think that I may have stepped up anyway — but I’m not sure that I would have, had it not been having that focus or introspective look,” spurred by Mary’s essay assignment. Sandmann did donate the kidney, and now, a couple years later, the boy is doing well.

That’s maybe taking the community outreach to an extreme, but it’s the thought process instilled by the Langhorst family. Mary admits the exercise was meant to be thought-provoking, without intending even to read the final essays.

Sometimes, being a Master of the Pork Industry has little to do with what goes on in the barns.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like