’19 Pork Masters: 50 years later, customers still come first

Hog equipment manufacturer meets needs of pigs, pork producers.

“Sold out.” Those were the words Billy Herring heard 50 years ago when he tried to place an order for concrete slat flooring for the new nursery he was building on his family’s 300-sow, farrow-to-finish farm in Newton Grove, N.C. The Raleigh, N.C.-based manufacturer wasn’t just out of stock on slats; it was sold out for the year.

That didn’t deter the young pork producer, though. Relying on ingenuity and experience, Billy constructed his own slats. His attention to detail and quality workmanship shone through the project, and soon other farmers were calling Billy to help construct flooring for their farms and were placing orders for future projects.

“I was just trying to manufacture quality equipment to take care of my family,” Billy says.

Five decades later, Billy’s company, Hog Slat Inc., is the largest contractor and manufacturer of hog equipment in the world. It fills orders for pig and poultry farmers across the United States, Mexico, Poland, Romania, Ukraine, Russia, Germany and China. The company has remained family-owned, with Billy and his sons, Tommy, David and Mark, each managing parts of the business. In addition to their 30,000-sow farm, the family oversees hog construction jobs all over the world and employs more than 2,000 people.

A global corporation now, Hog Slat has never faltered from the business model Billy built the company upon. There is no middleman.

“Our model has been direct to the customer since Day 1. That’s the way Daddy established it, and that’s the model we still follow,” says Tommy, president of Hog Slat. “When we first started, we were producing concrete slats for pig farmers. Today in the pig and poultry world, we have our own proprietary products that we can deliver, direct to the farmer, with 85% to 90% of the products the farmer needs.”

Since Billy started the company in 1969, Hog Slat has truly been filling the needs of U.S. pork producers and beyond through quality construction, equipment and products; convenient locations; and a strong devotion to customer service. For these contributions to the industry and more, Hog Slat and the Herring family have been selected to the 2019 Masters of the Pork Industry class.

Turning pigs to profit

Born and raised on a tobacco farm in Sampson County, Billy learned early how to profit off pigs. At the age of 12, his father gave him his first pig. He fed it, and when it sold, he had enough money to buy a bicycle.

After graduating high school in 1954, Billy took his first job working at the family general store, where he stayed on for eight years. When he and his brothers purchased Newton Grain and Feed, Billy assumed management responsibilities of the feed mill. Soon after, the family expanded the hog business with a 300-sow, farrow-to-finish farm. In 1968, Pork Chop Hill Farm was up and running, farrowing pigs in-house and feeding on the ground.

Proving naysayers wrong

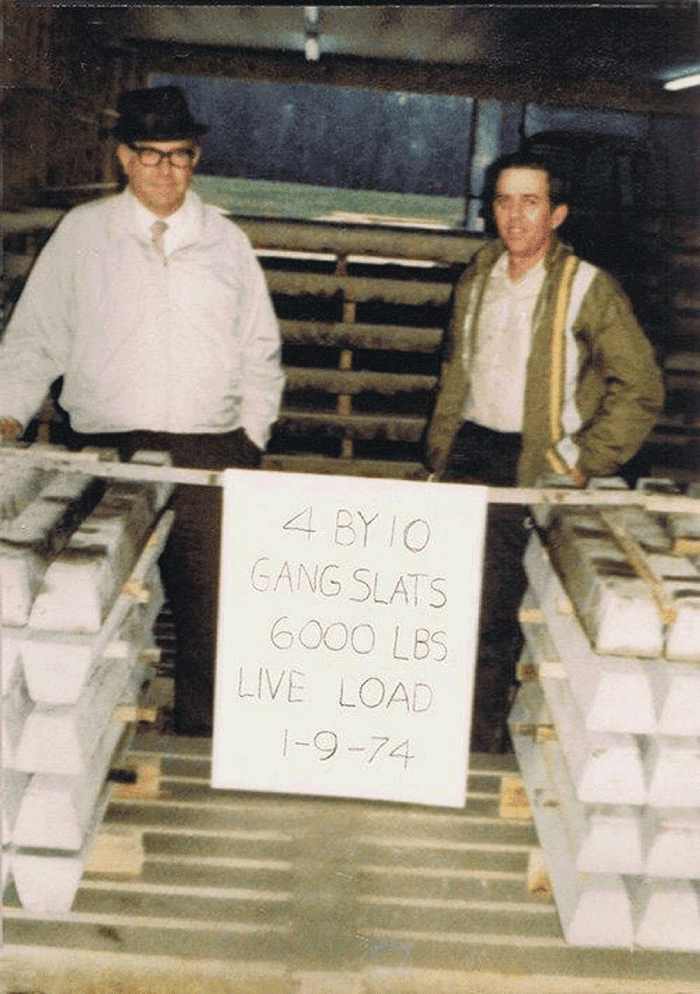

In 1969, when Billy started building slats, single slats were the industry standard. But by 1973, he saw the opportunity for gang slats — a group of seven slats set up in a 4-by-10 or 4-by-8 configuration.

While the Raleigh-based firm made single slats, the Herring family was not aware of gang slats being in existence. For single-slat systems, the labor required was more intensive. Gang slats could be put in using a crane.

“We could cut labor costs by 80% and increase the quality of the product, because a gang slat was a lot stronger than seven individual slats,” Tommy says.

Most people told Billy it wouldn’t work.

“One guy told me, ‘You are going to double your inventory because you have both singles and gangs,’ ” Billy recalls.

Despite the naysayers, Billy made the choice to go against the trend.

Airplane slats

In 1975, Hog Slat had its first big job: putting in gang slats at First Colony Farms in eastern North Carolina, a 10,000-sow, farrow-to-finish operation.

“It kept us rolling,” says Magdalene Herring, Billy’s wife and Hog Slat’s first secretary.

Next came the farrowing slat, or as the pig farmers named it, the “airplane slat”: constructed with a center concrete slat for the sow to lie on, and then creep area with a rubber coating and expanded metal.

“It had something that simulated wings, so they called it an airplane slat, but it was really just a combination of floors,” Tommy says.

That was a new concept in 1983. Today, a combination floor is common within the industry.

Riding industry waves

By the late-1970s, Billy was looking for areas to expand the business beyond slats. He first hired a company to build equipment for Hog Slat, but by 1977 he had decided to bring the manufacturing in-house, building the company’s first equipment plant in Newton Grove.

“I thought there was a need there for better equipment than was on the market,” Billy says.

When the early 1980s hog market failed drastically, and the construction market slowed down, Hog Slat started making feeders. While the company still had the slat business, the feeders kept Hog Slat going and allowed it to keep the manufacturing staff on board.

From 1979 to 1984, with extra salespeople on board, Hog Slat started to explore outside of North Carolina — to Iowa and Indiana — to diversify and not be dependent on just its own region.

This wasn’t the first time the family had ridden out the markets. In 1979, Hog Slat opened a plant in Cobb, Ga. In 1981, the company was forced to close the plant when 40% of the hogs left Georgia.

“The hogs left, so we left, too,” Billy says.

By 1982, Billy had decided to try his hand at building a hog farm for a father and two sons in North Carolina. Roy Poage, general manager of DeKalb Swine Breeders, came to look at the breeding stock farm after it was constructed and made Billy an offer.

“He came into my office and said, ‘Billy, you are going to build a hog farm for me in Kansas,’ ” Billy says. “I said, ‘I am?’ And he said, ‘Yes, you are.’ ”

Heavy construction

In the spring of 1985, Billy and Magdalene moved to Kansas to begin construction on the DeKalb sow farm. At this time, Tommy assumed the company’s management.

After building the farm in Kansas, Billy says Hog Slat got into “construction heavy.” The next big job was 200 buildings in Virginia. A joint venture between Smithfield Foods and Carroll’s Foods, each project was to house 1,000 sows. Billy and Magdalene moved to Virginia in 1986 to start the project; David, who was now finished with school, followed in September 1987. It was April 1989 before the project was finished.

“We were nomads,” Magdalene says.

After those jobs, Billy began “experimental work,” as he calls it. David says his father was really Hog Slat’s research and development at the time.

David took on more hog farm construction jobs, first moving to Oklahoma in 1989 to build another farm for Poage. He was there for 18 months before moving to Grundy County, Iowa. Another slat plant was soon built in Humboldt, Iowa.

“Billy’s timing at getting into the business when industry in eastern North Carolina was growing and modernizing gave him the ability to sell products, and he took advantage of not only creating new products, but improving existing products and making them better, more efficient and more practical from an economic standpoint,” Tommy says.

It also helped that the rest of country saw that change and innovation in North Carolina and was receptive to those products and technologies coming to the Midwest, David says.

Reputation preceded Hog Slat

As customers started to move business internationally, the Herrings soon found their construction business was requested outside the U.S.

“Our reputation to deliver and manufacture a good-quality product resulted in numerous requests from international customers,” Tommy says.

Today Hog Slat maintains three slat plants in China, three in Mexico, one in Romania, one in Poland and six in the U.S. — as well as three steel manufacturing plants in the U.S. and one in Romania.

“Our international investments serve to spread our risks,” Tommy says. “If the U.S. market is down, maybe the Chinese, Russian or Mexican market is up.”

Shopping locally

Around 1998, when there were too many pigs and not enough shackle space, the Herrings realized that a tremendous amount of their income was based on new construction, and they needed to become less dependent on new construction.

The Herring family started experimenting in retail sales to provide services and products to existing farms. It was something they had been doing since the early 1980s, but sometimes parts were hard to come by — especially in rural regions.

The Herring family started to focus on retail sales and expanded to 85 stores in the U.S. Each store essentially carries the products needed for any existing pig or poultry farm. Stores are strategically located where there is an appropriate number of pig or poultry farms to support.

Since they opened their retail outlets, the Herrings say the feedback has been nothing but positive.

TDM Farms

In addition to Hog Slat, the brothers also run TDM Farms (named for Tommy, David and Mark), an integral part of the family business. In 1983, they bought a 350-sow farm from a customer, and in 1986 added another 500-sow farm. Then, in 1988, the family turned its focus to building a 1,200-sow research farm.

The research farm enabled the Herrings to test products, ventilation, energy use and various other things. They hired a young college graduate, Mary Ann Martin (now Mary Ann Christensen of Christensen Farms), to be a statistician and to measure results.

“We could model a trial on that farm and measure the results,” Tommy says. “We gained a lot of valuable information. It was a working hog farm, and it had to make a profit, and it was part of TDM, but it provided a lot of the knowledge we gained to pass on to our customers.”

In 1996, they doubled the research farm to 2,500 sows; half of the farm is an environmentally closed facility, the other half is a curtain facility now.

Today, TDM Farms has more than 30,000 sows, and it includes a feed mill and grow-out operation in Indiana.

“As an equipment producer running a pig farm, it gives us insight into what our customers face every day and allows us to make better decisions within both of our companies,” Tommy says. “That has really helped us on the international market as well.”

“By having the production facility, it validates the products we sell to customers. Sometimes the great ideas don’t turn out to be great ideas; but the only way you can truly measure it is statistically — other than that, it is just an idea,” David says. “That has been one of the great assets for Hog Slat as an equipment provider: to be able to measure the products and be innovative and create new products as these opportunities are put before us in our production facilities.”

Having TDM Farms has also allowed the brothers to showcase new technologies to customers and handle customer requests for tests.

One of the most successful findings to come out of the research farm was trying a wean-to-finish production model, Tommy says.

“We thought if we placed weaned pigs in the finishing floor and never moved them, they will grow and perform better,” Tommy says. “We tried it in 1992, and it worked really well; and we started doing that, and now the industry does it on a large scale.”

Customer always right

Besides operating its own pork production system, Tommy says Hog Slat’s business model is very similar to many pork producers across the U.S. As a fully integrated company, Hog Slat’s staff does all of its own manufacturing, distribution, construction and sales. There are no profit centers in between.

Hog Slat’s philosophy has also stayed true to Billy’s original business model.

“The Hog Slat engineering team is made up of 10 people, whose marching orders or direction is, anything they develop or put in front of the market has to be as good as, or better than, competing products,” Tommy says.

It must meet both the pig and the pig farmer’s needs.

“I really think because we grow pigs, pay the bills on pigs every week, and manage labor issues with pigs every week, it gives us a unique ability to understand our customers’ needs and deliver products and services that they truly need,” Tommy says. “Understanding the unique needs of the pig and the pig farmer gives us an unrivaled advantage over our competition.”

Tommy says he is proud of what his family and employees have achieved, and that the company’s employees and their unwavering dedication are the foundation of Hog Slat’s success.

Finally, and most importantly, the family says the company has never wavered from its commitment to its customers.

“This saying may be beat to death, but nowhere is it truer than here. The customer is always right, he’s always going to be right, and we are always going to back up the customer. We’ve made mistakes over the years, but we’ve always, and will always, make them right and fix them,” Tommy says. “Our customers are our first important asset, and our employees are our second important asset — and we look after both of them.”

“We’ve always had tip-top customers and employees,” Billy says. “That is one big thing — having great people.”

Hog Slat family

From highly educated to no formal education, Hog Slat’s staff is a diverse group, but Tommy says he would put them against any Harvard MBA any day.

“I’m just proud of the company, the employees, their effort and ingenuity and their creativeness and stubbornness,” Tommy says. “We have accomplished a lot as a family, but that family includes a lot of employees that have just done an amazing job.” In the last 50 years, they have seen employees stick around 35 to 45 years.

“They refer to it as ‘my company,’ ” Magdalene says.

“That is the heart and soul of our company,” Tommy says.

Faith, family, friends

The 83-year-old founder of Hog Slat spends most of his days now helping out at TDM Farms with son Mark. Looking back over the last 50 years, he says he has no regrets and will be eternally grateful to his friends at North Carolina State University, Murphy Brown, Carroll’s Foods, Prestage Farms, Lundy Packing and Smithfield Foods for their support over the years.

He’s also thankful for wife Magdalene’s efforts in holding down the family fort.

“He put all his time and energy into the business,” Magdalene says. “I put my time and main energy into supporting his efforts.”

Finally, Billy says his faith helped him get to where he is today.

“I attribute my success to good employees, hard work, my wife and my family, and most importantly, the Lord,” Billy says. “When I say my Lord, he has guided all my decisions along the way.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like