Understanding the cash market and futures curve

Understanding the relationship between cash and futures can help producers better manage their hedge positions and leverage the information being provided by the market to take advantage of opportunities that may present themselves.

One of the main economic functions of the futures market is price discovery. Participants from all over the world place bids and make offers in a dynamic auction to determine the value of a commodity or financial instrument at any given point in time. Because multiple contracts trade simultaneously for the same commodity in different time periods, both nearby as well as in deferred months and years, this price discovery process is multi-dimensional. It not only reveals the current or “spot” value but also expectations about how that value will change over time. Studying this relationship, referred to as the forward curve, can provide valuable information on how market participants anticipate price movements for the cash market. It also can help hedgers refine position structure to protect risk in deferred time periods.

Cash and futures relationship

Futures contracts are called derivatives because they derive their value from the underlying cash market. Based on the contract specifications, futures either settle to the cash market through physical delivery as is the case with contracts like corn, or are cash settled where their final value at expiration is determined by some sort of an index, as is the case with hogs. In either case, prior to a contract’s expiration and convergence with the cash market, there is a difference in value between the spot cash price and the nearby futures price. This difference, or basis, changes over time where in some cases the cash price may be at a premium to futures, and in others a discount.

Looking beyond the nearby futures contract, deferred futures also may be trading at premiums or discounts to the cash market as well as to nearby futures. One of the reasons why deferred futures prices may trade at a premium to spot prices could be seasonality. For many commodities, there is a normal tendency for prices at certain times of the year to be higher or lower than other times of the year, and the futures curve reflects those seasonal tendencies. Another reason may be fundamental.

As an example, there may be a shortage of the commodity in the spot market although the pipeline might suggest ample supply in a deferred period. In such a case, the spot or cash price would be trading at a premium to forward futures prices.

Hog market

The current structure of the hog market offers one example of the relationship between cash prices and the forward futures curve. Notwithstanding a recent recovery, the cash hog market has been under heavy pressure since late-January as supplies have been larger than expected. After starting the year at prices very close to the average of the past 10 years, the CME Lean Hog index declined almost $22 per hundredweight between late-January and early April as hog slaughter and pork production have posted strong year-over-year increases from 2017 (see Figure 1). Total hog slaughter during the first quarter was 31.075 million head, up 3% from a year ago; however, pork production of 6.645 billion pounds during the quarter was 3.7% higher than last year as hogs are coming to market at heavier weights.

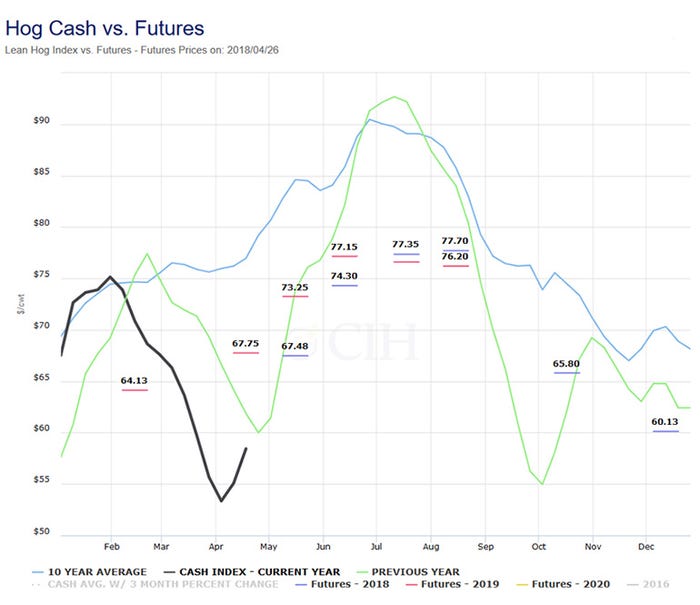

Figure 1: CME Lean Hog Index versus Futures

Moreover, the latest USDA Hogs and Pigs report indicated that supply growth is likely to continue through the summer and into fall. The hog breeding herd on March 1 was estimated at 6.2 million head, the largest since 2008 with producers reporting that they intend to farrow more sows than a year ago for the next two quarters. March-to-May farrowing intentions were up 2.1% from 2017 while the June-to-August quarter showed an increase of 1.4% from last year. Recent news of China’s decision to impose retaliatory tariffs on U.S. pork imports hasn’t been helpful either as much of the offal goes to that market with limited opportunities for other outlets.

Looking at Figure 1, you will notice that the loss in value in the CME Cash Hog Index and subsequent recovery was very similar to last year (green line) albeit around three weeks early in 2018. You will also notice the hash marks spread across the page, which represent futures prices as of April 26. The blue lines correspond to 2018 futures while the red lines are the values for futures in 2019. Each value is displayed in the middle of the month when the futures contract expires. The 67.48 value in blue between May and June represents the current value of May 2018 futures which is where the black line is headed over the next few weeks. Given the two values have to converge at expiration, this means that either the black line (spot cash market) needs to rise further, and/or the price of May futures needs to come down in order for the two to converge by mid-May.

The summer futures prices with June at 74.30, July at 77.35, and August at 77.70 indicate expectations for a continued rise in the cash market or CME Lean Hog Index over the next few months as would seasonally be expected, although those expectations are much more muted than the increase in cash prices we witnessed last year when looking at the green line. This likely is due to the factors previously mentioned with larger hog slaughter and pork production relative to last year and increased trade uncertainties.

From a hedging perspective, while the futures market represents a fair estimate of value for summer hogs based on what is currently known, it may make sense for a producer to retain upside flexibility on their price hedges in case the cash hog market is stronger over the next few months. As a counterpoint however, it should be noted that August Lean Hog futures are also currently trading at their highest premium relative to the CME Lean Hog Index in the past decade (see Figure 2).

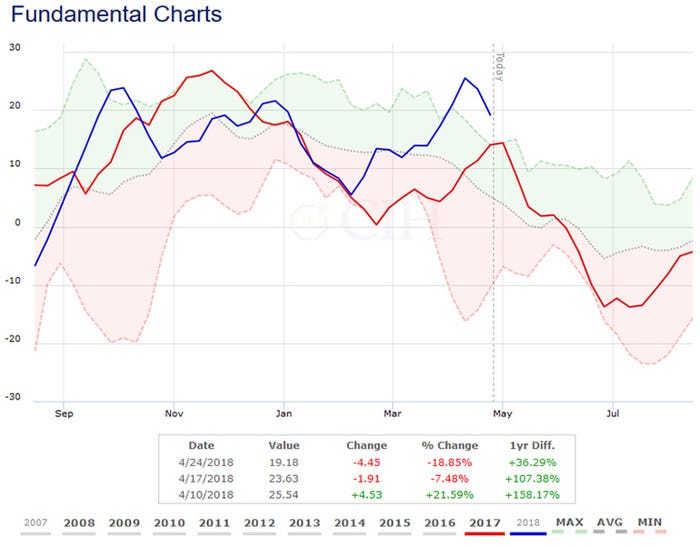

Figure 2: CME 2018 August Lean Hog Futures minus CME Lean Hog Index

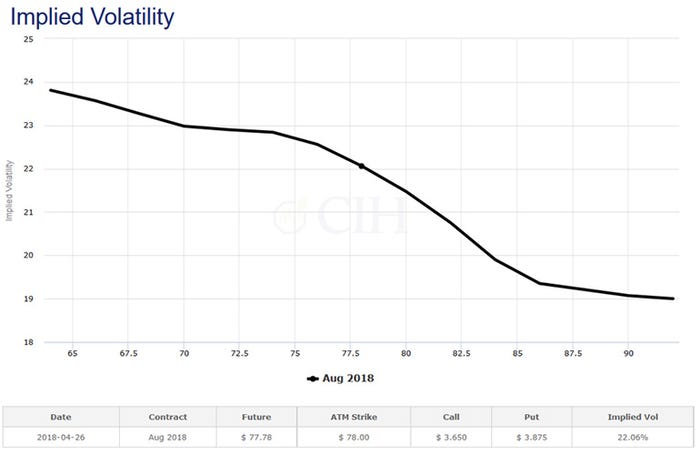

An example of how a producer might address both of these considerations in a hedge would be adding long call options to a short futures hedge or cash sale in the local market against their summer marketings. The August futures are trading around 77.70, so the producer might purchase a call option with an $80 or $82 strike price to address the opportunity cost in a higher market against pre-existing sales either in the cash market or on the board. They may even choose to offset part of the cost of purchasing the call by selling a put option below the market. This not only would lower the cost of adding upside flexibility to the hedge, but also take advantage of the current option volatility skew in the market as higher strike calls are trading at lower implied volatilities relative to lower strike puts (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: August hog options implied volatility skew

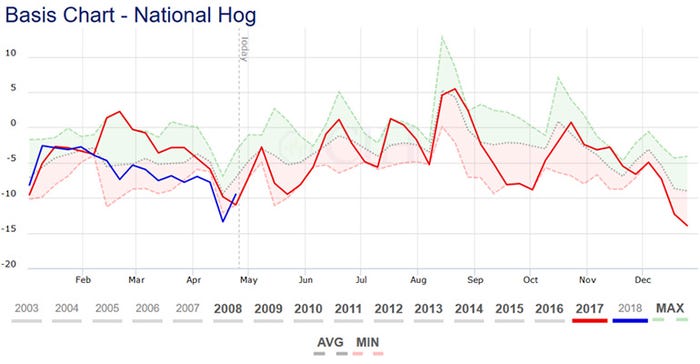

Another consideration for a hog producer from a hedging perspective concerns cash basis levels. With the cash market trading at a discount to futures, hog basis is currently negative and has actually been running at or near new 10-year lows through April (see Figure 4). Because of this, a producer would only want to deliver hogs against the minimum amount necessary to meet packer commitments, and possibly even slow down hedge removals against their marketing schedule.

Figure 4: Cash hog basis (National — LM HG203)

The forward curve is an important component of the price discovery process in the futures market and provides valuable information for a risk manager to consider when evaluating their exposure. Understanding the relationship between cash and futures can help producers better manage their hedge positions and leverage the information being provided by the market to take advantage of opportunities that may present themselves.

There is a risk of loss in futures trading. Past performance is not indicative of future results.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like