Will history of 1998 repeat itself?

We can certainly experience negative margins, but a return to rock bottom is not on the horizon (unless, of course, African swine fever makes its way to the United States).

December 10, 2018

Indelible dates:

Dec. 7, 1941

June 6, 1944

Nov. 22, 1963

Sept. 11, 2001

You likely know the significance of most of those dates because you lived them or you had a good grade school history teacher.

We are approaching the 20th anniversary of the day that will live in infamy for the pork complex — Dec. 16, 1998.

Production overtaxed shackle space for an extended period; people and plants needed a rest. Live hog prices hit rock bottom at 8 cents per pound. Farmland was a stand-alone entity at that time (subsequently acquired by Smithfield) and drew a line in the sand, willing to pay a minimum of 16 cents per pound regardless of any additional downward pressure. Bankruptcies ensued, death threats were hurled at the owners of larger operations as they were seen as “the reason” for the price collapse, financial and family relationships were strained.

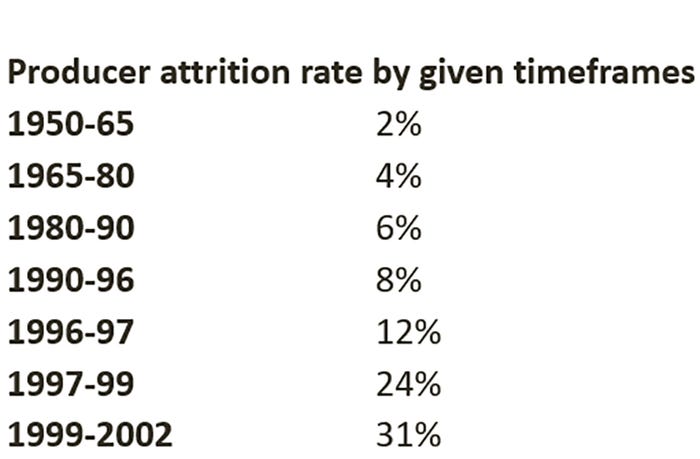

The table below shows that we had experienced some attrition of producers since the 1950s, it accelerated precipitously during this the late-1990s and continued for a few years thereafter. Some producers opened their pens to set animals free instead of continuing to feed them. Producers exited the industry like a crowd rushing for the door at the end of a concert. The Farm Credit System (to their credit for compassion or blame for interfering with economics) bent over backwards to keep people in business, ignoring covenant violations and continuing to fund operations with negative net-worth. They did not save all, but the ag lenders generally did a good job of creative problem-solving to keep operations afloat. My mouth gets dry and my heart rate increases as I write this; it is physical response to a traumatic memory. We lived the anguish of late-1998 as a waking nightmare and most of 1999 as a lingering haze.

Most of you can remember this time and its sobering impact, how it changed lives and shaped the direction of the pork industry, and how we vow to never return to that state again.

But is our behavior a bit antithetical to the threat? Have 20 years passed and, with it, a bit of the acute feelings that we experienced during that dark time? Are we marching toward another potential crisis with a similar vulnerability as we had back during the Reagan administration?

Perhaps a little compare/contrast is in order. Per the Glenn Grimes packer study from January of 1999, spot purchases as an industry constituted roughly 80% of all market hogs. A good chunk of hogs with a pricing agreement were of the corn-soy matrix variety. Ergo, the vast majority of the hogs were negotiated on a week-to-week basis, setting up a collision course when we taxed packer capacity. What ensued in the wake of the disaster was a huge migration toward some type of shackle space agreement, driven largely by the banking community, to protect against a repeat of this situation.

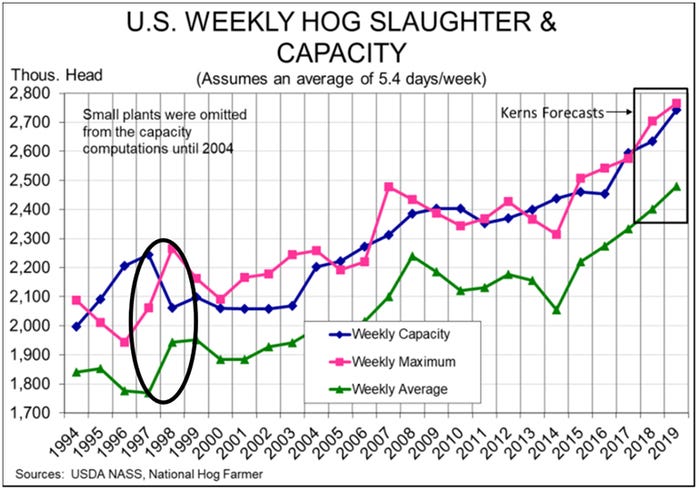

The unintended consequence of this logic is the reduction of spot market hogs to roughly 3% of the weekly slaughter and on the cusp of no longer statistically representing fair market value. We have traded one risk for another and, perhaps, it has not been a good trade for the production community. We are probably not on the edge of overrunning packing capacity anytime soon nor will the lenders be too liberal with expansion funds in the absence of assurances. The attached chart shows the compression of plants closing (blue line) with production increasing (green line) that came crashing together in the fall of 1998. Our current trajectory does not indicate a return to this situation in the near future.

The current financial health of the industry is very different to where we sat in 1998. Per data from our friends at Compeer, working capital was approximately $1,400 per sow in 2017 (a record in their database) and a stark contrast to where we sat in 1998. If we were to value inventory at market prices, we would have had negative working capital and net worth calculations in 1998. A silent change between then and now had little to do with pork production profitability. The ethanol boom that transformed land in the Midwest from about $2,500 per acre to well over $10,000 per acre provided a windfall to all pork producers with land ownership. There have been a lot of moving parts over the past 20 years.

Our risk tolerance is significantly better today than it was then. Our risk management behaviors are also better and more widespread. The largest operations were participating in risk mitigation practices in 1998, the bulk of the industry went with the prevailing wind under the auspices that the law of averages would work itself out. Perhaps that made sense then; running our operations as businesses makes sense now.

So, in conclusion, are we are standing upon the threshold of history? Do we see a repeat of the crisis that was 1998? I do not think so. We are not nearly as leveraged, we are more integrated, we have both the tools and capacity to lock-in profits. We can certainly experience negative margins, but a return to rock bottom is not on the horizon (unless, of course, African swine fever makes its way to the United States).

On another note, I am just back from Argentina where we met with several individuals involved in the soybean export and crush trade. Their industry had a bad year, mostly due to the drought there last year that thwarted physical movement of product. Fortunately for them and us, this year does not look to be a repeat. The wheat harvest is finishing with good yields and good quality, beans are going in behind the wheat with ample moisture and no threats from the meteorological community anywhere on the horizon.

First-crop corn, about half of their total production, is pollinated and looks good. We participated in a dove hunt while in Argentina and the attached picture has the corn crop as a backdrop. It all looks good. Brazil is in similar shape. No known problems and even difficulty in fabricating issues.

The G20 was taking place while we were in Buenos Aires, snarling traffic even more in a city that is characterized by congestion. The ag industry is in a nice little afterglow of the meeting with everyone playing nice in its wake. You are likely to see some Chinese purchases of U.S. beans in the near future (my best guess is in the 6 million metric tons range) to fill in for the Chinese Strategic Reserve. This is not product that is destined for commercial use, but is for government stocks rebuilding. This may placate some who see it as a gesture of improved U.S.-Sino relations.

I suspect the transactional dealings will have a very abrupt ending. Not because of any souring of relations, but because of economic reality. Brazil is on queue for record soybean production — 125 mmt is my best guess — and Argentina is on their heels with a rebound in its production. We are going to simply overwhelm the world with available supplies during a time when the U.S. crop is in bins (and the carry in the market will encourage further storage) and the South American crop harvest is rolling with product looking for a home. I suspect soy premiums in the United States and South America will come under significant pressure after the first of the year — good news for anyone who needs to secure soybean meal basis during that timeframe.

Comments in this column are market commentary and are not to be construed as market advice. Trading is risky and not suitable for all individuals. Joseph Kerns, 515-268-8888

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like