Still time to play defense and minimize losses

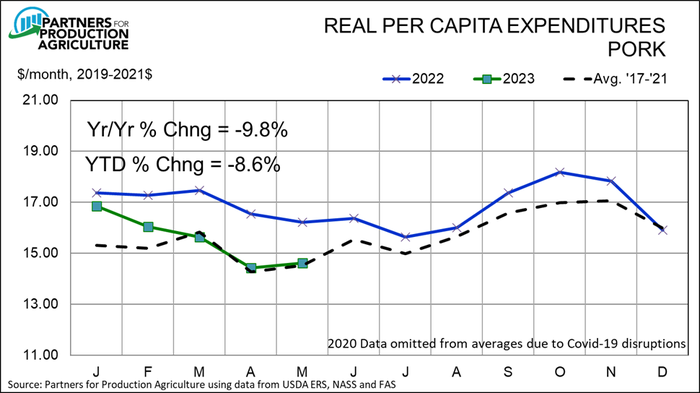

Real per capita expenditures for pork in May were 9.8% lower than one year ago bringing the YTD change for pork RPCE to -8.6%.

July 10, 2023

It is no secret that pork and hog demand are not what they were in 2021 and 2022. I've made that case repeatedly this year as demand at all levels of the hog-pork sector have fallen back to levels witnessed in the decade ending in 2020. A return to recent robust demand levels would be one ingredient in a recipe to pull producers out of these significant financial losses.

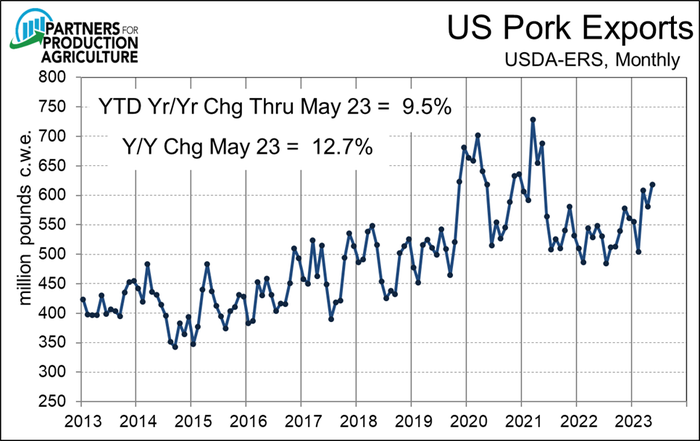

Last week's export data for May from USDA indicate that export demand is helping. U.S. pork exports totaled 618.1 million pounds carcass weight, 6.5% more than in April and 12.7% more than last year. May was the best month for U.S. pork exports since May 2021 and brings the year-to-date total to 2.87 billion pounds, 9.5% larger than one year ago. See Figure 1.

The value of U.S. pork exports was up 9.3% versus May 2022. YTD export value is up 11% from last year. Average export prices were slightly lower in May but are higher for the year. Higher volume and higher price can mean only one thing: Higher export demand.

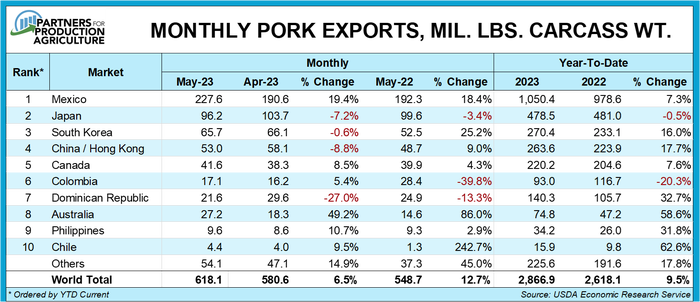

Mexico remains far and away our largest export customer and continues to perform extremely well. May shipments to Mexico were the second largest on record and were 18.4% larger than one year ago. YTD exports to Mexico are up 7.3% and are over twice the amount shipped to our number two market, Japan.

Figure 2 shows export date through May. Seven markets are up double-digits from 2022, year-to-date. That list includes China/Hong Kong. The trouble is that the double-digit growth there is from a very low level one year ago.

In addition, U.S. pork imports were sharply lower, yr/yr, in May at -25.8%. The biggest reason is a big reduction in exports from Canada — since Canada accounts for about 60% of all of our pork imports. Year to date, imports are down 24.2%.

Let's put those numbers in context. U.S. pork exports, not including variety meats, account for 23.5% of U.S. production last year and, in my current forecasts, will run about 25% of total carcass weight production this year. A 9.5% increase in those shipments would amount to about 2.4% of total U.S. production. Imports constituted 4.9% of total U.S. production in 2022 but I expect that number for fall to 3.9% this year. A 24.2% decline in imports would amount to about 0.9% of production. All told, change in net U.S. pork trade this year has reduced domestic pork availability by roughly 3.3% and have clearly been supportive to prices.

The story for domestic demand is not nearly as rosy. Real per capita expenditures for pork in May were 9.8% lower than one year ago bringing the YTD change for pork RPCE to -8.6%. See Figure 3. Note that pork RPCE remains slightly above its five-year average, supporting my observation that demand has returned to levels more "normal" than the robust levels observed in 2021 and 2022.

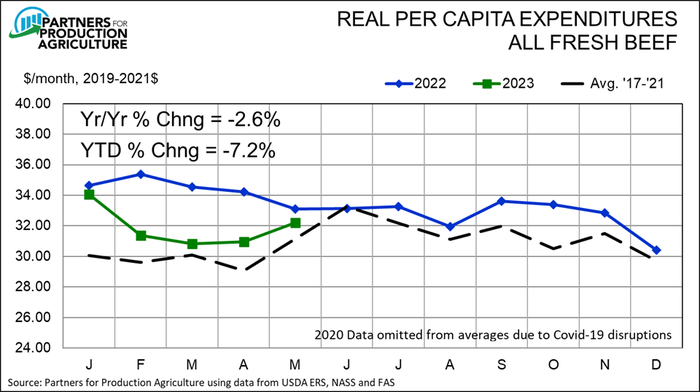

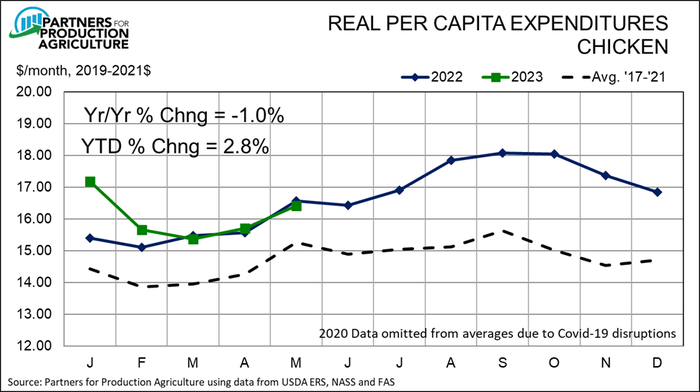

Monthly RPCE charts for beef and chicken appear in Figures 4 and 5 to illustrate that pork is not alone in this lower consumer-level demand situation. Beef RPCE is down 7.2% year to date after lagging prior-year levels by 10% or more every month for the second half of 2022. Chicken RPCE is still very near year-ago levels but that needs to be contrasted to double digit increases during the second half of 2022. So, while chicken demand is still stable, it certainly "ain't what it once was!"

Total RPCE for beef, pork and chicken was down 4.0%, yr/yr, in May. YTD total three-species RPCE is down 5.2% from one year ago.

The challenge of course is that the reduction in domestic demand applies to about 75% of our output while the help of exports applies to 25%. Export growth must be huge to offset the headwinds we are seeing on the domestic front.

So is there hope for domestic demand? Remember that pork demand is determined by consumer tastes and preferences, income levels, and prices of competitor and complement goods. The last of those is more of a theoretical construct but the first three are critically important. There is always hope but we must keep these "sources" of demand clearly in mind.

Tastes and preferences are the "black box" of demand in that they are very difficult to observe and quantify. In fact, only in-depth consumer studies can give us much insight into the decision workings of consumers and those, of course, are influenced greatly by factors such as advertising, promotions, news events, etc. They are difficult to read, even more difficult to impact and they normally change quite slowly.

Income levels are quite observable and appear to have been a huge factor in meat/poultry demand since the pandemic began in 2020. Roughly $7 trillion was pumped into the U.S. economy in 2020 and 2021. For much of that time, opportunities to spend those funds were limited by closures and, in many cases, shortages of a broad range of consumer products. It is, in my opinion, no coincidence that meat/poultry demand surged shortly after this influx of cash and dropped dramatically when the cash, including the amount that was saved, was gone from consumers hands.

Consumer incomes are increasing again but inflation is keeping a lid on the growth of real income levels. This more organic growth may help meat/poultry demands but the impact will be small and slow when compared to the large influx of Covid relief money.

Which leaves us with relative prices. Chicken prices are still relatively low meaning they are not helping pork demand. Beef prices are high and will almost certainly go higher as cow-calf operations shift from liquidation to expansion mode and pull heifers out of the feedlot and slaughter supplies. Higher beef prices will be positive but cross-price elasticities are not large so the impact on domestic pork demand will not be sufficient to move it back to 2021-2022 levels.

Recent rains and additional corn acres have reduced forecast production costs for the remainder of this year and into 2024. But my forecasts for the Iowa State University average cost for farrow-to-finish operations are still near $90/cwt carcass, implying costs for average producers in the $95-$97 range.

Those costs levels require dramatic demand improvements if producers are to see profits of any size through the end of 2024. I think the chances of that much gain, short of a repeat of the Covid cash infusions, are very unlikely. And I don't think a repeat of those cash outlays is coming either.

Unfortunately, it is still time to play defense and minimize losses for the foreseeable future.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like