Pork Producers Deal with the Credit Crunch

Serious problems that developed in the agricultural credit market in 2009 could escalate in the next 2-3 years. The impact on pork and dairy producers will be magnified by the fact that the livestock portion of the farm operations often represents the majority of the business' assets

April 15, 2010

Serious problems that developed in the agricultural credit market in 2009 could escalate in the next 2-3 years.

The impact on pork and dairy producers will be magnified by the fact that the livestock portion of the farm operations often represents the majority of the business' assets. If the livestock operation fails, all of the assets of the business will have to be liquidated, including the land base.

While dairies tend to fail as individual businesses, many hog operations are contractually part of integrated supply chains. Some very well-managed hog operations could be in trouble, not because of their own performance, but because their integrator fails and the entire supply chain goes down with it.

The reality is that there has been little involuntary exit from agriculture in the last 4-5 years. Unfortunately, extended boom periods tend to be followed by a cleansing period of about three years, and a hangover effect can extend beyond that. And, I have observed, the half-life of the lessons learned from a financial crisis lasts about 10 years.

It is important to remember the function of a competitive market is to drive the economic return to the average producer to economic breakeven through supply and demand responses in both input and output markets. In equilibrium, the top-end producers are profitable and growing, the average producers are hanging in there, and the bottom end are losing money and being forced to exit the industry. Business success and survival depend on continuous improvement at a pace necessary to stay out of the back of the pack.

The same is true for lenders. During the boom periods, growth is strong, profits are increasing, loan losses are low and competition among lenders is intense. As farm income deteriorates, loan problems begin to mount and commercial lenders begin to pull in their horns as they begin experiencing loan losses, and their lending staff gets bogged down in dealing with adverse credit.

Fortunately, really serious industry-wide problems occur only every 20 to 30 years. The last time was the farm financial crisis of the 1980s. Unfortunately, some signs point to a period of financial stress extending over several years. How severe the problems become will depend primarily on three factors:

How soon net farm income rebounds;

What happens to land values; and

How soon and how much interest rates increase.

Although financial regulators and Congress are always more reactive than proactive, their actions significantly affect how lenders operate. The current administration is increasing the money supply and providing more liquidity in the financial markets, but commercial bank and Farm Credit System regulators are aggressively working to ensure that lenders recognize and mitigate risks.

The Rules Change

A major regulatory change is that loan loss reserve requirements are now expected to be more forward looking and anticipatory and less dependent on recent history. Only a few years ago, regulators and accounting firms were criticizing lenders for excess loss reserves that were built to absorb the longer-term, cyclical downturns. Some lenders that were required to roll out what were deemed “excess” reserves are now being criticized for either not being adequately reserved or needing higher capital levels to absorb shock events.

The current climate has affected lender behavior. First, all lenders have less appetite for risk. This is being manifested in several ways:

Lenders are requiring more and better documentation from borrowers, as well as closer monitoring of performance after loans are made.

Fewer exceptions to underwriting standards are being made.

Emphasis has increased on repayment capacity, including more analysis of accrual adjusted net income rather than just cash basis tax returns. The Farm Financial Standards Council has recognized for nearly two decades that cash basis accounting can lag true profitability by two years or more in terms of both upturns and downturns.

Working capital and liquidity are also more important. Cash may be king, but a business can be making payments and going broke by refinancing, selling assets, building accounts payable and deferring the replacement of capital assets. By itself, staying current on payments may not be enough to keep borrowers' loans out of trouble.

Repricing terms are shorter. A loan may be amortized over 15 or 20 years, but repriced every five years. This practice is driven largely by the lender's ability to match fund the maturity of the loan or to sell the loan in the secondary market.

Higher risk premiums are being built into interest rates. In part, this reflects that inadequate premiums had previously been priced into higher risk loans, often because of competition.

Advance rates are lower, such as requirements for higher down payment or equity.

The use of Farm Service Agency (FSA) guarantees has increased significantly. Nationally, operating loan guarantee volume was up over 30% and mortgage guarantees up 9% in 2009. FSA actually ran out of funding for the operating loan guarantees in 2009. The funding for both programs has been increased by 20% for 2010, but the shortfall from 2009 will have to come out of that as well. Borrowers who will require FSA assistance must start early. FSA's staff will be swamped and, if demand increases as expected, the funding could run out before the year is over.

These changes reinforce the importance of several factors. Interest rates and debt structure can be as important as debt levels in terms of the impact of debt on producer's financial performance, and rates are subject to changing much more rapidly.

Current concerns in financial markets are the potential for increases in interest rates and inflation resulting from increased federal debt, and the creation of new entitlement programs.

Interest rates are about as low as they can get, so the only way to go is up. If the economy rebounds and the private sector reenters the capital debt markets, there is a potential for a crowding-out effect. The federal debt will be issued and refinanced, but the rates are determined by the level of competition in the market.

Recently, the federal government has had little competition. Since nearly 40% of the federal debt is held by foreign investors, the problem could be exacerbated if inflation occurs and the dollar is devalued. This would make U.S. treasuries less attractive to investors, except at much higher rates. The Federal Reserve could end up between the proverbial rock and a hard place, needing to raise interest rates to curb inflation, but at the same time not wanting to stall economic growth.

While interest rates are likely to increase, they probably won't go up significantly in 2010. The current economic recovery doesn't have enough legs under it and I have not yet seen a new economic engine emerging.

The Value of Land

Lenders recognize that management is the primary determinant of success or failure, but it is also extremely hard to quantify in risk rating models. Many studies have found that the top quarter of producers, in terms of profitability, tend to be only about 5% better than average, whether in terms of costs, production or marketing. But they do it over and over again.

By way of analogy, remember that the future Hall of Fame baseball player with a .300 lifetime batting average gets only one more hit every 20 times at bat than the player who hits .250 and just manages to hang on.

As for loan losses on a broad scale, the ultimate financial impact on the financial health of the agricultural sector will be determined by and reflected in land values. The basic reason is that 87% of total farm assets are in real estate. With the increase in land values in recent years, the total debt:asset ratio for the agricultural sector is at historically low levels — but the number can be very deceiving.

First, 70% of farm operations carry no debt. The use of credit is more concentrated among capital-intensive and larger operations that depend primarily on farm income for debt repayment. Most of the shift away from debt over the last 10 years has occurred on farms generating less than $500,000 annual gross sales. Then, add the fact that 42% of land in farms is owned by non-operator landlords and of the 58% owned by farm operators, 61.3% is owned by farmers with less than $250,000 annual gross sales.

Because both the net worth and the underlying collateral for many farm loans, even operating loans, is real estate, and because the majority of farm debt and farm income is concentrated on commercial-scale farms and ranches, the value of land is critical to the risk of loss in the event of default faced by agricultural lenders.

The market value of land is determined at the margin — the prices of land sold. If farm income drops and debt servicing problems occur, forced sales will increase. If able buyers get nervous about reduced income prospects and believe land values could fall, they will sit on the sidelines. This would exacerbate the problem and land values would fall even further. To this point, land values have held up and land markets have tightened in part because landowners who don't have to sell have few good options for investing elsewhere, and land is considered a good hedge against potential inflation.

Changes in land values obviously aren't evenly distributed. Land type, quality and location differ significantly, and so will the market impacts. Declines in value have already occurred in recreational and transitional land markets, and on marginal quality agricultural land.

If land values fall by less than 10% from their peak, the impact will be minimal. But, a 20% decline would cause significant problems, and more than a 30% decline could result in a restructuring of the industry similar to the 1980s. One of the major problems is that declines in land values not only result in foreclosures and loan losses, they also decrease the market value equity of all land owners.

Psychology of the Markets

Unfortunately, markets tend to overreact on both the upside and downside. American economist Alan Greenspan referred to this response as irrational exuberance/fear and said that 80% of market economics is psychology.

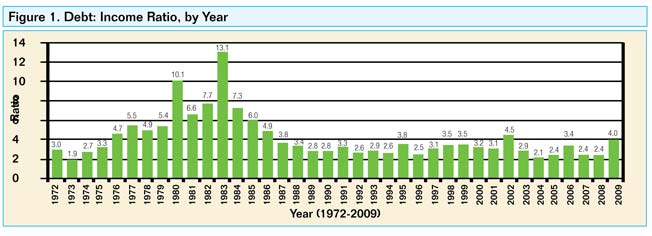

Experience has shown that when it comes to predicting financial problems, the debt-to-income ratio is a much better leading indicator than the debt-to-asset ratio. For example, Figures 1 and 2 show that the debt:income ratio indicated problems started to develop in 1977, while the debt:asset ratio didn't start reflecting anything negative until 1981. The question is whether the drop in net farm income from $87 billion in 2008 to an estimated $57 billion in 2009 is an aberration or the beginning of an extended downturn.

If net farm income remains below $60 billion in 2010 and 2011, there will be problems. If it falls below $50 billion, the problems will be serious.

Lessons Learned

The past two years in commodity, real estate and financial markets have made it abundantly clear that changes can occur quickly. We have also learned that Black Swan events — the large-impact, difficult-to-predict events, such as terrorism, pandemics, global recession — are real. The tails of economic and financial distributions are larger than the assumptions of a normal distribution.

Most risk models capture only “normal” periods, and that includes the rating services, such as Moody's, Dun and Bradstreet. This experience has several lessons that must be heeded:

Econometric models tend to be data dependent and backward looking. Boards and managers need to rely on judgment and experience and learn to look for leading indicators outside of their immediate environment.

Although linear trends are good indicators of behavior and performance, they seriously understate the potential rate of change created by the external environment, including the impact of technological change. Tipping points often cause exponential rather than linear changes for both upturns and downturns. Timing is critical — for getting in, expanding, cutting back or getting out. The academic and personal experience indicate that timing is the main difference that separates the top 10% from the rest of the top 25% of managers and businesses.

Employee and management incentive compensation systems need to be evaluated and redesigned. People ultimately do what they are incentivized to do. We have learned over time that incentives that focus too much on volume or cost minimization can be disasters. Even systems that focus on profitability have often failed to effectively factor in the risk:reward relationship, not just for the individual, but also for the business.

In conclusion, the current level of financial stress and the increasing emphasis on risk management are going to make the credit acquisition process more rigorous for all agricultural producers. This will mean a more performance-based approach to being prepared to borrow.

You May Also Like