Even a grim week has flicker of brightness

Without some government help, many producers will not be able to absorb this kind of loss. Another massive — and maybe final — round of consolidation looms.

May 11, 2020

The grim work of balancing market-ready hog supplies with a crippled processing industry must start in earnest soon. In fact, it must start this week, as given slaughter levels the past three weeks and what I believe was intended marketings (i.e. the number of hogs that should have been slaughtered) imply that 1.894 million hogs are backed up on U.S. farms. And that is assuming 260,000 market hogs have already been euthanized. I think that number is likely high.

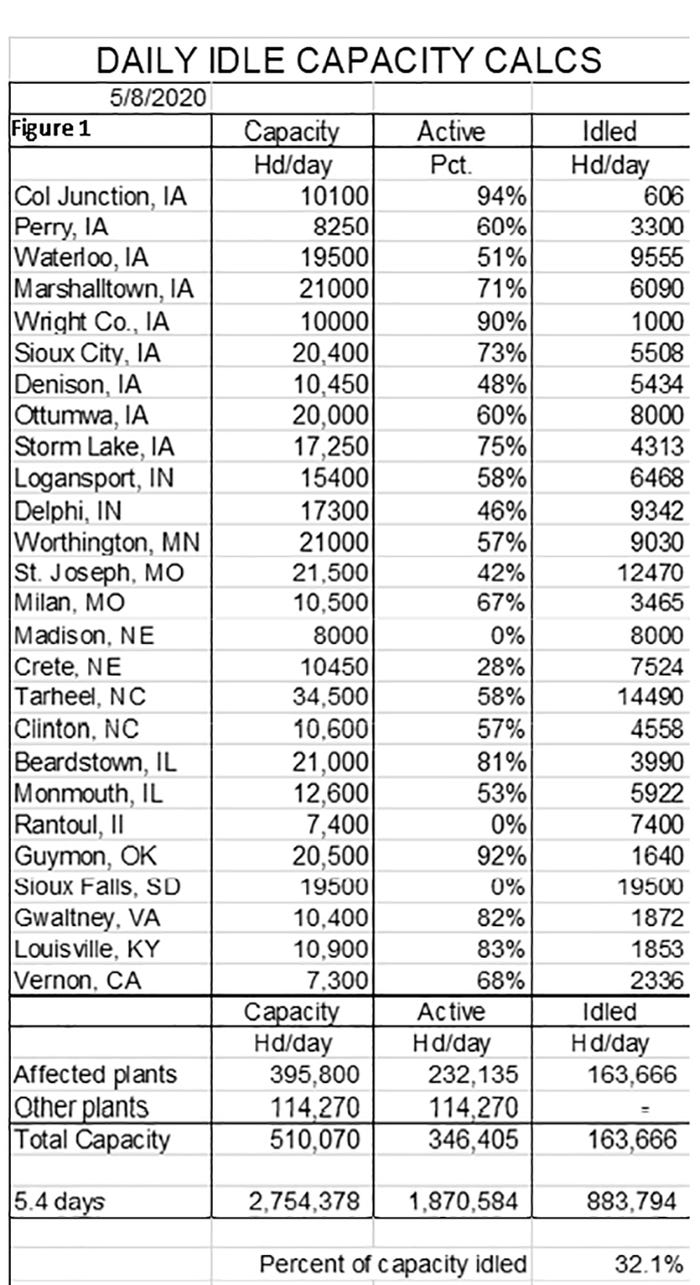

But first some good news. Last week saw total idle capacity drop from 42.9% on May 1 to 32.1% Friday. All but three plants were operating at some level Friday and big plants at Waterloo and Marshalltown both in Iowa; and Delphi and Logansport in Indiana got rolling again. A few other plants improved operating rates while a few others began to struggle. Our tally of plants that have seen challenges and their operating rates as of May 8 appears in Figure 1.

When you've been in the deep, deep dark, any light looks promising, but this is encouraging for everyone, I think. Of particular note is Tyson's Columbus Junction, Iowa, plant that has, for all intents and purposes, returned to normal operations since coming back online April 24.

Whether other plants can achieve this recovery level is critical to long-term implications. Only time will tell how long-term these recoveries are as we relax movements state by state. Let's hope and pray they hold.

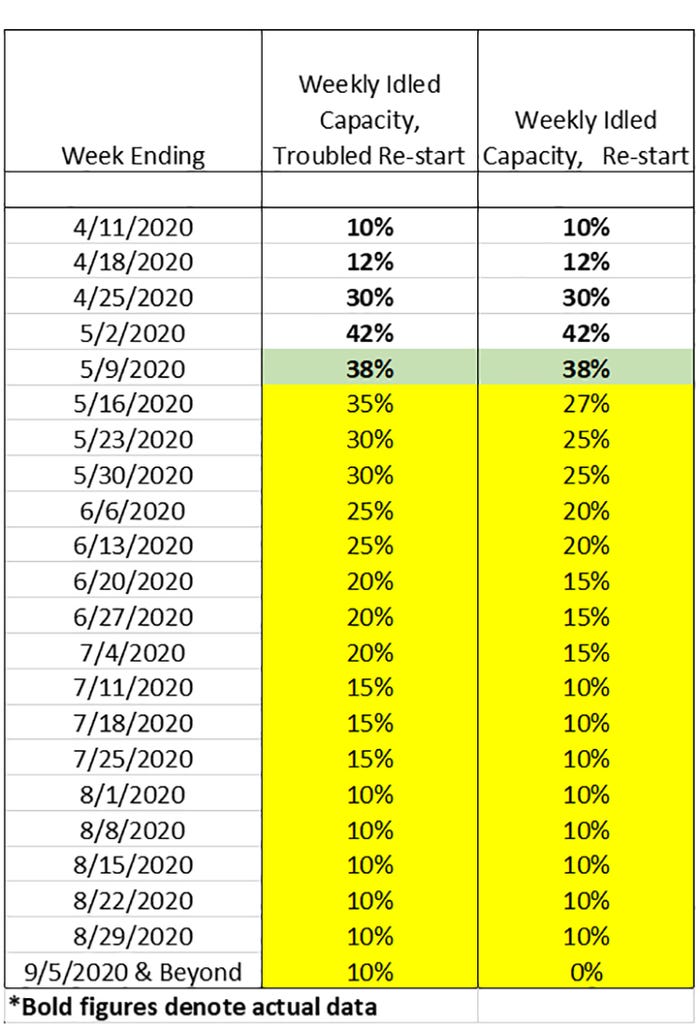

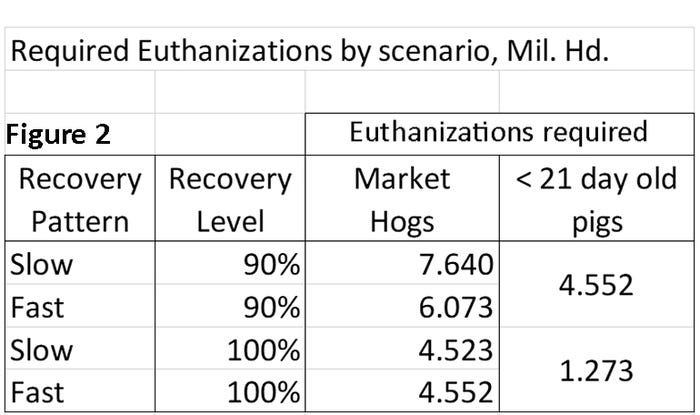

The reason for that is simple: The outlook is still dire. Figure 2 shows the results of my calculations comparing expected (i.e. my forecast) weekly slaughter figures to those that could be expected under the two scenarios shown in the table above. These differ by the rate of improvement and the ultimate rate to which the sector recovers.

Last week's improvement from 42% to 38% was our first improvement. There is talk that total slaughter this week could recover to 2 million head. That is certainly doable if Friday's three still-shuttered plants (Sioux Falls, Madison and Rantoul) open back up and others steadily increase their throughput. Sioux Falls and Madison are expected to resume operations today. No word yet on Rantoul. The 2-million head level would imply 27% — thus the pattern in the right-hand column.

The more important factor in the long run is, not surprisingly, whether plants can get back to 100% of pre-COVID capacity. Noel White, president of Tyson Fresh Meats, has stated that their plants will achieve this goal. Tyson's Columbus Junction plant would lead us to conclude it is possible, but it is a sample of one observation at this point.

Some observers (myself included) don't see how that will happen at all plants and fear that some plants may not get close. It all depends on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines and the physical abilities of plants to implement them. How far will people have to be spread out? Will personal protective equipment be enough? What about barriers? How big is the fab floor? The questions are pretty endless.

Figure 2 shows that the answer is critical for what must be done and the costs those actions would impose. My figures say the worst case would cost producers $766 million to $1.093 billion (market hogs plus baby pigs), plus euthanasia and disposal costs if they have to pay for everything from their own pockets.

Without some government help, many producers will not be able to absorb this kind of loss. Another massive — and maybe final — round of consolidation looms.

And there is another issue. It has been an elephant in the room for years and now that elephant is on the rampage: Value determination.

The demand for hogs is derived from the demand for pork while the supply of pork (not just the quantity but the combinations of the quantities that producers will supply at alternative prices) is derived from the supply of hogs. The factor that transforms wholesale pork demand to hog demand and hog supply to wholesale pork supply is the marginal cost of slaughter and processing. Marginal cost is the change in total cost for a one-unit change in quantity.

But what if the change in quantity can only be zero? That is, what if the slaughter and processing sector is up against hard and fast constraint. Since the denominator of the marginal cost ratio is near zero, then the marginal cost itself is infinite and the demand for hogs is what we economists call perfectly inelastic — the quantity cannot change regardless of what happens to price.

Such is our situation. The Western Corn Belt negotiated price on Friday was $38.09 per hundredweight. It could have been $10, or it could have been $50. Packers would have bought the same number of hogs regardless. Why was it $38.09? Because that is the price the buyers decided to pay. There is no supply and demand interaction at play here. The demand for hogs is perfectly inelastic at the level of operational packing capacity. The supply of hogs is perfectly inelastic at some higher quantity. Packers can just choose the price.

This situation won't last forever to this degree but a mismatch between marginal hog supply and marginal hog demand is almost certain on a frequent basis now. And it impacts what you can do in managing risk. The May contract will expire on Thursday. At present, the negotiated hog price is about $38 while the CME Lean Hogs index is $66.18, and the May contract is $66.325. That's a bit of a basis problem.

The average cost of hogs slaughtered on Friday (the 201 price) was $71.12 with the swine/pork market formula at $68.05. That value is part negotiated (net was $37.59 on Friday) and part cutout ($116.50 on Friday). So what is that futures contract actually trading?

And finally — it is a huge discrepancy for some producers to be getting 90% of a $116.50 cutout (i.e. $104.85 per hundredweight or about $225 per head) and others — some (many?) of whom tried to get a cutout value-based contract — were getting the $38 per hundredweight or about $81.70? I think the best horse trader deserves to be rewarded but is thriving versus failure the correct alternative?

Watch for Joseph Kern's discussion next week about these pricing situations. I think he will even include some possible solutions.

Source: Steve Meyer, who is solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly owns the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset. The opinions of this writer are not necessarily those of Farm Progress/Informa.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like