Euthanasia perspectives of Spanish-speaking caretakers

Conducting euthanasia has been reported as a significant stressor for animal caretakers.

May 4, 2021

Swine caretaker turnover rates and labor shortages plague the U.S. swine industry. According to a National Pork Board report in 2016/17, swine caretaker turnover rates were 35% and 20% for large and small to mid-size farms, respectively. In addition, “production worker” was identified as the most difficult position for recruitment.

One option to manage labor shortages is to seek out qualified caretakers through visa programs. This option is being utilized on U.S. swine farms with J1, H1B, H2-A, and TN-visa holders, as well as Green Card holders, being recruited by 41% of large producers and 9% of the small to mid-size producers (National Pork Board, 2017).

Despite the labor force from immigrant and migrant caretakers, a 2018 study (Boessen et al.) commissioned by the National Pork Producers Council reported negative growth rates in rural U.S. counties, which threatens pig producing firms. Immigrant and migrant caretaker rates entering rural labor markets, which had historically offset negative growth rates, have also been declining due to improved economic conditions, declining population growth, easier access to higher education in Latin America, stricter immigration controls and enforcement, and an aging domestic immigrant labor force (Boessen et al., 2018; Hanson et al., 2017). Currently, Hispanic and Latino caretakers make up 19% of the total animal production and aquaculture workforce in the U.S. (Bureau of Labor Statistics & Population Survey, 2020). Therefore, it is important to understand workplace factors and perceptions affecting this demographic to effectively recruit and retain qualified swine caretakers.

Conducting euthanasia has been reported as a significant stressor for companion and laboratory animal caretakers (Rohlf & Bennett, 2005; Scotney et al., 2015). Animal caretakers have reported “feeling stressed” when they had to euthanize animals they had been caring for, which is labeled the caring-killing paradox (Arluke, 1994). In the swine industry, Matthis (2004) noted that although 68% of all swine caretakers reported that they “feel fine” after conducting euthanasia, 29% expressed negative emotions, such as, “feeling sick to their stomach”, “thinking about euthanasia all day”, or were “generally sad.” Furthermore, Matthis (2004) reported, “Spanish-speaking employees were the least willing to euthanize pigs compared to the English-speaking employees” (44% vs. 29%).

Despite limited research investigating swine caretaker euthanasia perceptions, recent exploratory studies have concluded that there is an opportunity to address caretaker mental wellbeing through animal euthanasia resources and training (Edwards-Callaway et al., 2020; Simpson et al., 2020). Thus, our objective for this project was to investigate Spanish-speaking TN-visa caretaker demographics and swine euthanasia perceptions on a commercial sow farm.

Twenty-eight caretakers from a single swine company in central Iowa were enrolled in this study. All visa-holding employees at this company held a TN-visa. All caretakers completed a Qualtrics survey in Spanish, adapted from work published by Rault et al. (2017). Questions were categorized into 12 sections: empathy affect, empathy attribution, negative attitudes toward pigs, confidence knowing when a pig is healthy, relying on others to help provide pig care, insufficient knowledge regarding sick or compromised pigs, willingness to seek knowledge in dealing with, treating, and managing sick pigs, perceived time constraints, using available resources (i.e. the veterinarian, coworkers) to obtain advice in diagnosing sick pigs, comfort with the euthanasia process, trouble deciding and avoiding euthanasia, and feeling bad about euthanizing. Non-demographic questions were structured using a five-point Likert scale (1=strongly disagree to 5=strongly agree), with a “prefer not to answer” option. For this article, the last three sections will be further discussed: (a) comfort with the euthanasia process, (b) trouble deciding and avoiding euthanasia, and (c) feeling bad about euthanizing.

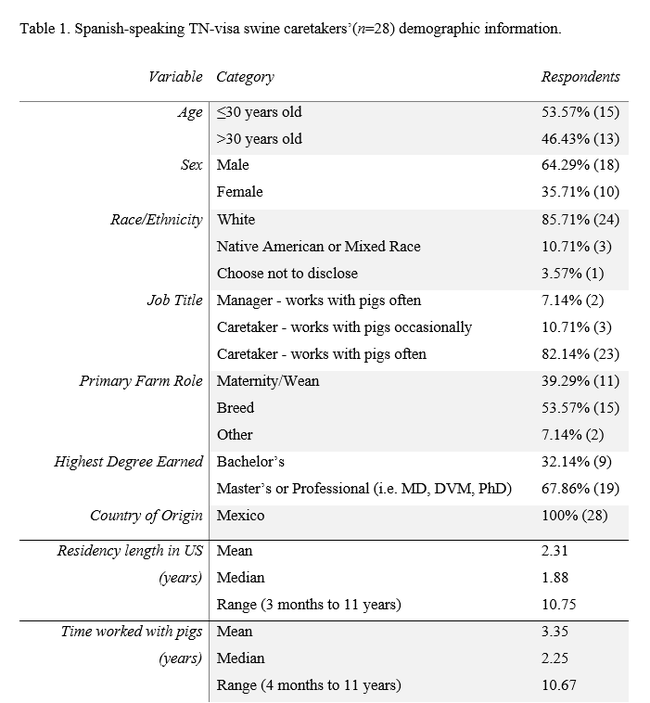

Demographics: Fifty-four percent were ≤30 years of age and 46% were >30 years of age, comprising 64% male and 36% female. All caretakers were migrant workers from Mexico. The majority (68%) had a master’s or professional degree and 32% had a bachelor’s degree. The average time caretakers have resided in the U.S. was 2 years and 4 months, and the average time working with pigs was three years and four months (Table 1).

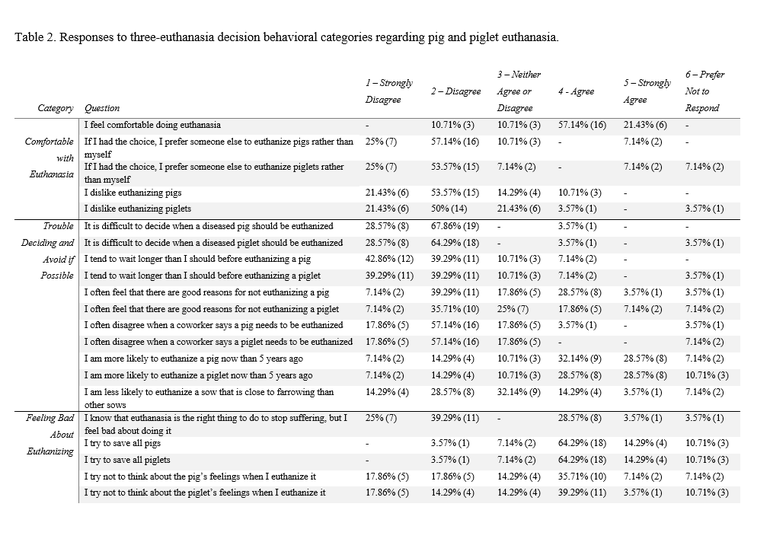

Results: When comparing responses to questions on comfort with the euthanasia process, trouble deciding and avoiding euthanasia, and feeling bad about euthanizing, little to no difference was observed between adult pigs and piglets. While the majority of caretakers felt comfortable conducting euthanasia (79%), some did indicate being uncomfortable (11%). Nearly one-fifth (18%) indicated that they were less likely to euthanize a sow close to farrowing. Avoidance of euthanasia may compromise the animal’s welfare and contribute to non-compliance of procedures in audits. Moreover, about one-third (32%) and a quarter (25%) of caretakers agreed or strongly agreed, respectively, that there are good reasons not to euthanize adult pigs or piglets. When euthanasia is conducted, 43% of the caretakers reported being able to dissociate from thinking of the animal’s feelings. Dissociation is a coping mechanism experienced during very difficult events. Caretakers (32%) also indicated feeling bad about euthanizing pigs and piglets, despite acknowledging that it was the correct course of action (Table 2).

Overall, preliminary results of this research provided insight into the perspective and challenges experienced by Spanish-speaking caretakers regarding aspects of comfort, decision and avoidance, and feelings surrounding the euthanasia of adult pigs and piglets. Providing clear guidelines on specific circumstances that absolutely require pigs to undergo euthanasia, along with education on the caretaker’s duty to avoid suffering in lieu of life preservation, may alleviate some of the negative feelings experienced. Furthermore, providing a support structure for the caretakers’ mental wellbeing before, during, and after euthanasia during on-boarding and on-farm training could be very beneficial in reducing the high caretaker turnover rates and retain caretakers on our swine farms.

Summary points:

TN-visa Spanish-speaking caretakers on commercial sow farms:

Majority reported being comfortable with euthanizing adult pigs and piglets.

A subset of survey respondents reported avoidance for euthanasia based on the animals’ life stage.

One-third of caretakers have general negative feelings about conducting euthanasia.

Sources: Jacob Yarian, Anna Johnson, Suzanne Millman, Jason Ross, Brad Skaar, Kenneth Stalder, Iowa State University; Monique Pairis-Garcia and Ivelisse Robles, North Carolina State University; Andréia Arruda, The Ohio State University; and Cassandra Jass, Iowa Select Farms, who are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

References

Arluke, A. (1994). Managing Emotions in an Animal Shelter. Animals and Society: Changing Perspectives, January 1994, 145–165. https://www.academia.edu/25664726/Managing_Emotions_in_an_Animal_Shelter?auto=download

Boessen, C., Artz, G., & Schulz, L. (2018). A Baseline Study of Labor Issues and Trends in U.S. Pork Production. March, 41.

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U., & Population Survey, C. (2020). HOUSEHOLD DATA 10 . Employed persons by occupation , race , Hispanic or Latino ethnicity , and sex [ Percent distribution ]. https://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat10.htm

Edwards-Callaway, L. N., Cramer, M. C., Roman-Muniz, I. N., Stallones, L., Thompson, S., Ennis, S., Marsh, J., Simpson, H., Kim, E., Calaba, E., & Pairis-Garcia, M. (2020). Preliminary exploration of swine veterinarian perspectives of on-farm euthanasia. Animals, 10(10), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10101919

Hanson, G., Liu, C., & McIntosh, C. (2017). The Rise and Fall of U.S. Low-Skilled Immigration.

Matthis, J. S. (2004). Selected Employee Attributes and Perceptions Regarding Methods and Animal Welfare Concerns Associated with Swine Euthanasia. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781107415324.004

National Pork Board. (2017). Employee Compensation & HR Practices in Pork Production 2016-2017 Report.

Rault, J. L., Holyoake, T., & Coleman, G. (2017). Stockperson attitudes toward pig euthanasia. Journal of Animal Science, 95(2), 949–957. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas2016.0922

Rohlf, V., & Bennett, P. (2005). Perpetration-induced traumatic stress in persons Who euthanize nonhuman animals in surgeries, animal shelters, and laboratories. Society and Animals, 13(3), 201–220. https://doi.org/10.1163/1568530054927753

Scotney, R. L., McLaughlin, D., & Keates, H. L. (2015). A systematic review of the effects of euthanasia and occupational stress in personnel working with animals in animal shelters, veterinary clinics, and biomedical research facilities. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 247(10), 1121–1130. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.247.10.1121

Simpson, H., Edwards-Callaway, L. N., Cramer, M. C., Roman-Muniz, I. N., Stallones, L., Thompson, S., Ennis, S., Kim, E., & Pairis-Garcia, M. (2020). Preliminary study exploring caretaker perspectives of euthanasia on swine operations. Animals, 10(12), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani10122296

You May Also Like