This little piggy went to a finishing barn

There are many trailer configurations on the market and such things as rear openings, roof vents and distance between the cab and trailer will impact air flow.

September 19, 2018

By: Jay Harmon, Steve Hoff and Brett Ramirez, Iowa State University Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering

Some piglets are seasoned travelers well before they reach market weight. Iowa State University, through funding by the National Pork Board, conducted a transportation study with three phases. In phase one, records from over 7,000 trips were analyzed to find trends in mortality rate associated with hauling weaned pigs (3,174 trips) and feeder pigs (3,882 trips). These trips were categorized by distance (< 370 miles, 370 to 560 miles, 560 to 750 miles, 750 to 930 miles and > 930 miles) and ambient temperature (cool/cold, < 59 F; mild, 59 to 77 F; and warm/hot, > 77 F). Dead-on-arrivals were recorded for each trip.

Trends in the transportation norms show that weaned pigs generally are traveling farther than feeder pigs. For weaned pigs, 63% of the trips were between 370 and 750 miles with 12% of the trips longer than 930 miles. Feeder pigs traveled less than 560 miles 81% of the time. Only 4% of the trips were longer than 750 miles and no trips exceeded 930 miles. In general, at least for the company providing this data, weaned pigs tended to travel considerably farther than the typical feeder pig.

Weaned pigs had a significantly higher overall mean mortality rate (0.0333% with a standard error of 0.0150%) as compared to feeder pigs (0.0243% with a standard error of 0.0110%). Mortality events appear to be confined to larger events on a few number of loads. Low percentages of DOAs (<0.5%) were associated with 96.6% of weaned pig trips and 98.7% of the feeder pig trips. Weaned pig mortality was the lowest in mild weather (59 to 77 F) and the highest mortality occurred in warm/hot weather (>77 F) at the longest distances. Feeder pigs were likewise more susceptible to warm/hot weather mortality than cooler temperatures. Overall, this may tell us that haulers do a good job of moderating the interior climate in trailers during cold weather, but only so much can be done during hot weather.

A second phase of the study tracked 78 individual loads of weaned pigs, examining the number and location within the trailer of DOAs and temperature conditions. Average distance was 480 miles, taking 8.5 hours of travel time. Loading time averaged 82 minutes and unloading averaged 32 minutes. Piglet weight averaged 15 lbs. Average trip mortality was 0.031%, with only 10 of the 78 trips (12.8%) having any mortality at all. Although the upper deck and lower deck had no statistically significant difference (p>0.05) in mortality, numerically there were more mortalities in the upper deck in summer and more in the lower deck in winter.

Temperatures in the various locations within the truck during winter/spring/fall weather tended to be highest in the upper front compartment and lowest in the lower rear compartments with other compartments performing similarly. During summer the high air flow tended to equalize the temperatures throughout the trailer. It is important to note that these comparisons allowed for the hauler to adjust side-slats based on their normal procedures. Therefore, the uniform temperature distribution was a combination of trailer performance and management of trailer openings by the hauler. A less-experience hauler or a different trailer configuration may have greater differences by area of the truck.

The wind tunnel indicated that air flow direction may be different than what most people perceive.

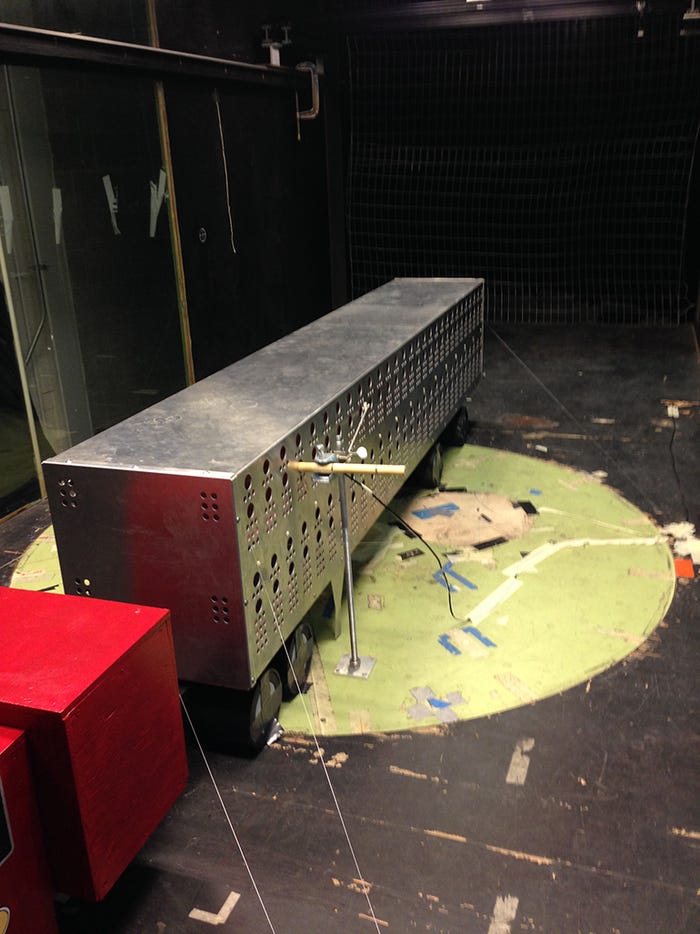

The last phase of this project utilized a 1/7th scale model in a wind tunnel to examine how air flows through the trailer. The model trailer was supplied by Eby Trailers. A plywood model of a tractor was added to the model along with scaled compartment gates. Air was measured within the trailer within each of 8 compartments using an air speed sensor. Trials were conducted with side openings always open and with front opens either open or closed. Trials were also run with and without compartment gates.

The air speed within compartments was taken as a percentage of the wind tunnel simulation speed. Generally, the speed inside the trailer ranged from 11 to 22% of the wind tunnel speed. In other words, a livestock trailer traveling at 60 mph would have air speeds inside (with it fully open) to range from 6.6 to 13.2 mph. Compartment partitions, which were about 50% open, reduced the air speeds within the trailer, indicating for heat stress purposes a more porous gating system may have merits.

The wind tunnel indicated that air flow direction may be different than what most people perceive. In general, when front vents are open, air tends to flow from the rear of the trailer toward the front. When front vents were closed most of the upper compartments flowed from front to rear and the lower compartments had air flowing rear to front. There are many trailer configurations on the market and such things as rear openings, roof vents, distance between the cab and trailer, and placement and amount of openings on the front will impact the actual flow.

You May Also Like