Keeping hog buildings in good shape longer

Research Review: Winter weather can be tough on hog buildings, and Canadian researchers sought potential solutions to mitigate the rapid deterioration of the buildings.

January 15, 2019

Researchers: Bernardo Predicala and J. Cabahug, Prairie Swine Centre and University of Saskatchewan College of Engineering Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering; and A. Alvarado and R. Baah, Prairie Swine Centre

On average, Canadian swine buildings are 20 to 30 years old, and over the next few years, these buildings will need renovation or may be replaced with new construction. This project set out to identify potential solutions applicable to Canadian conditions to mitigate the rapid deterioration of swine buildings. Those solutions would apply to most U.S. hog buildings as well.

A comprehensive literature search supplemented by an information survey of various stakeholder groups in the industry was carried out to compile and identify potential solutions to barn building deterioration.

An information survey had a total of 46 respondents comprised of producers (43%); builders (13%); materials and equipment suppliers (20%); and academic and research and development organizations (24%).

Results of the literature review and survey have identified various potential solutions for farm building material degradation which were categorized based on building design, material selection and treatments, and building management and animal production practices.

Many barns currently in use in the Canadian hog industry were built in the 1990s during the period of rapid upswing in the pig industry (Brisson, 2014). These were mainly based on the existing barn designs available at the time. Most of these barns have almost totally enclosed shells, and mechanical ventilation systems composed of fans, inlets and exhaust outlets to maintain favorable conditions for the pigs year-round.

In the winter, ventilation is usually turned down to a minimum level to lower heating costs. This, however, leads to higher levels of moisture and corrosive gases, varying thermal conditions, and presence of dust and decay microorganisms. The minimum ventilation rate and likelihood of strong winds in some areas in the winter months results in recirculation of exhaust air back into the barn, leading to poor in-barn air quality.

As a consequence, rapid deterioration of structural members (e.g., walls, eaves, ceiling, attic, plenum, etc.) is inevitable due to prolonged exposure to recirculated moisture and corrosive gases (Meyer et al., 1988). Thus, potential solutions or strategies are needed to address these issues and subsequently mitigate the accelerated degradation of swine barns.

Materials and methods

The overall objective of this project was to develop and evaluate measures and strategies to mitigate accelerated deterioration of swine buildings. The main approach was to conduct a comprehensive literature review and information survey to identify potential solutions applicable to Canadian pig barns (including, but not limited to, alternative ventilation configurations, surface treatments, innovative building materials, etc.) to address accelerated barn deterioration.

Results and discussion

About 60% of the producers and builders had issues with rapid deterioration of barn structural components. Specifically, the structural components that they had issues with were: roofing (50% of the respondents); penning and stalls (50%); exterior walls (40%); ceilings, trusses and/or attic, and feeding and drinking system (30%). No significant issues with accelerated deterioration have been identified in partition walls between two rooms, manure and drainage systems, or barn foundations.

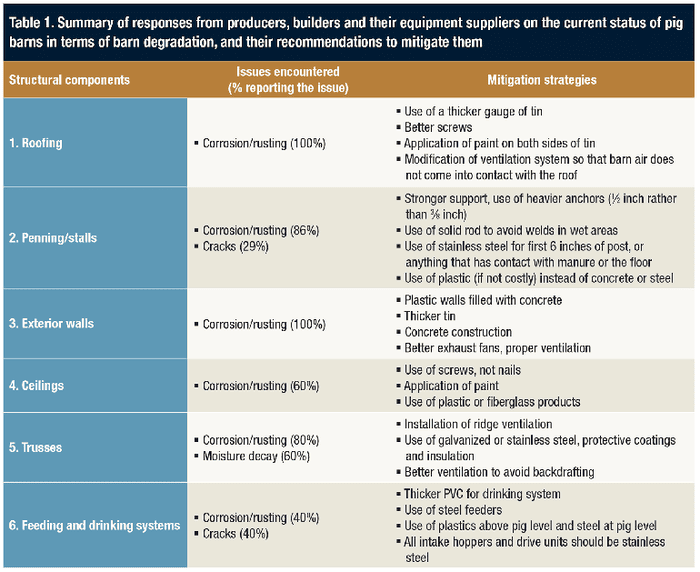

Table 1 summarizes the issues encountered by producers and builders related to barn deterioration and their recommendations for mitigation. The most common issue was corrosion or rusting of barn roof, penning or stalls, exterior walls, ceiling, trusses, and feeding and drinking systems. Some respondents pointed out issues related to moisture decay in trusses, cracks in penning or stalls, and feeding and drinking systems.

Mitigation strategies

Among the solutions to improve the building life span such as surface treatments, new material, ventilation systems, control and maintenance, the control and maintenance solution has been pointed out by the participants as the least expensive one and the easiest to adopt by producers. However, few consider maintenance improvement as the best option to improve building life span.

If the cost were not to be considered as a decision parameter, new building material and ventilation system improvements should be the priorities. For producers, when the cost of the technology is not considered, an adequate ventilation system, sufficient insulation and high-durability wall materials are the most attractive solutions to improve building life span.

Conclusion

Among all the potential solutions, techniques related to appropriate ventilation, environmental control and air treatments, improvement of corrosion protection efficiency of building materials, and effective building maintenance have been identified as the most promising solutions to rapid deterioration and have high adaptability to Canadian swine production conditions.

Although these strategies still need to be evaluated in an actual barn prior to full implementation for adoption in Canadian swine barns, outcomes from this project represent significant steps toward optimizing future barn renovations and constructions, as well as for possibly changing conventional swine production practices and farm building management.

As building and construction costs continue to rise, ensuring current facilities are maintained and operated to their fullest potential will ensure a robust hog industry. If facilities are not maintained to their fullest potential, not only does the potential life span of the facility decrease, but animal performance can also decrease as environmental conditions may not allow for optimal pig performance.

Researchers acknowledge the financial support for this research project by Swine Innovation Porc. The authors would also like to acknowledge the collaboration of Centre de développement du porc du Québec Inc. and Institut de Recherche et de Développement en Agroenvironnement in carrying out this work. Strategic program funding provided by Saskatchewan Pork Development Board, Alberta Pork, Ontario Pork, the Manitoba Pork Council and the Saskatchewan Agriculture Development Fund is also acknowledged.

For more information, contact Bernardo Predicala.

Sources: Prairie Swine Centre and the University of Saskatchewan, which are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like