Senecavirus strain change has industry watching closely

November 30, 2015

Senecavirus A, also known as Seneca Valley Virus, has been identified in the U.S. swine population since the late-1980s and has most commonly been associated with “Idiopathic Swine Vesicular Disease,” due to the fact that it was not one of the four foreign animal swine vesicular diseases (foot and mouth disease, swine vesicular disease, swine vesicular exanthema, vesicular stomatitis virus) when vesicular samples were tested at the Foreign Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory. Traditionally, most of the cases occurred in older swine and caused vesicular lesions on the snout, in the mouth, or along the coronary bands of the feet1,2

Iowa State University became involved in several of the early cases in late-July of this year that initially involved exhibition swine and in one instance, a commercial finishing site in South Dakota. In each of those cases, the state and federal officials were contacted, samples were pulled and tested for the four foreign animal vesicular disease pathogens, as well as for Senecavirus A. In all cases, the samples tested negative for any of the foreign animal vesicular disease pathogens, but positive for Senecavirus A by polymerase chain reaction from swabs of ruptured vesicles, vesicular fluid and oral fluids.

In August 2015, the pathologists from ISU began to screen cases of high pre-weaning mortality in neonatal pigs (less than 7 days of age) with diarrhea based on the Epidemic Transient Neonatal Losses syndrome that was described by Linhares et al3-4. They described several cases where SVA was positive by PCR in serum, feces and various tissues, but no distinct histological lesions were associated with the neonatal deaths. The neonatal mortality, was however, fairly short in duration which minimized the overall production impact to the breeding herds.

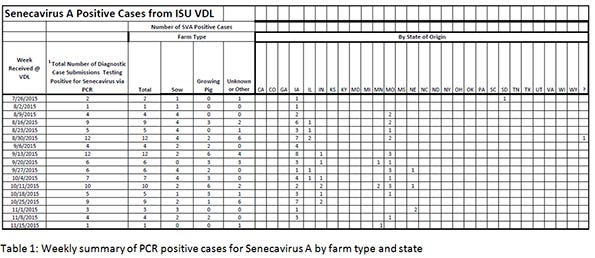

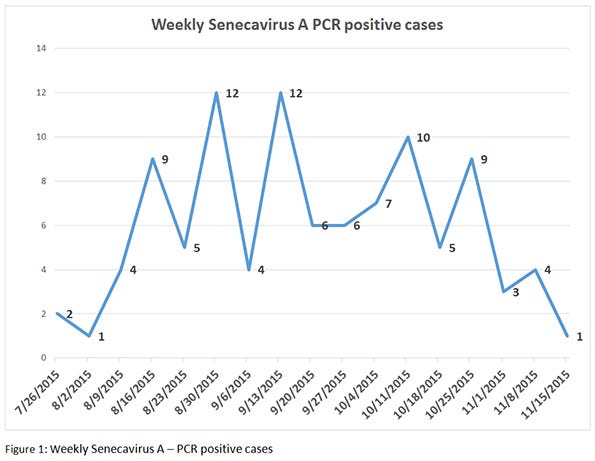

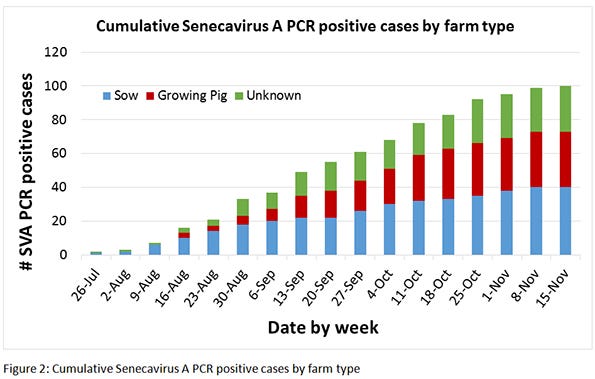

In an effort to quantify the incidence of new cases, ISU began to publish a weekly report of diagnostic cases submission that tested positive for SVA via PCR (Table 1). Each week, the total number of cases that had at least one positive sample for SVA on PCR was included in the weekly total. It would be important to note that each positive case would be independent of site, so it is possible that the same site could have submitted cases in the same week or different weeks and that they could be counted more than once. That case information is then broken out into the “farm type” and also by state of origin, both of which would have needed to be filled in on the submission form. The “farm type” was broken out into sow farms (breeding farms with suckling piglets), growing pig (nursery, finishing or wean-finish) or unknown/other. All of the exhibition swine would have been classified as growing pigs. The state of origin of the site where the case was submitted was the other breakout criteria and from this we can see that most of the cases were from Iowa, but have also seen cases in Missouri, Illinois, Indiana, Minnesota, Nebraska and South Dakota as well. Figure 1 shows the weekly cases of SV-PCR positive cases. We were averaging five to 10 cases per week in the months of August, September and October, but have seen a drop in cases to just a few cases each week so far in November, indicating a potential reduction in new cases. Figure 2 looks at the cumulative cases of SVA-PCR positive cases by farm type since the end of July. We appear to be at about 100 total cases of SVA with the cases fairly evenly split between sow farms and growing pigs.

Figure 1 shows the weekly cases of SV-PCR positive cases. We were averaging five to 10 cases per week in the months of August, September and October, but have seen a drop in cases to just a few cases each week so far in November, indicating a potential reduction in new cases. Figure 2 looks at the cumulative cases of SVA-PCR positive cases by farm type since the end of July. We appear to be at about 100 total cases of SVA with the cases fairly evenly split between sow farms and growing pigs.

SVA is not a new virus, but certainly something has changed as we are beginning to see many more cases associated with it than what has been seen historically. In fact, it has been shown that currently circulating strains are significantly different than historical isolates5. It is important to remember when vesicular disease is suspected (e.g. lameness, snout and/or coronary bands lesions), the farm veterinarian and state/federal officials should be contacted immediately (before any further pig movements). State and federal officials will determine the next course of action. Because of the similarities to disease that are foreign animal vesicular diseases, we need to be diligent to test these cases and make sure they are associated with SVA and not one of these other vesicular diseases.

SVA is not a new virus, but certainly something has changed as we are beginning to see many more cases associated with it than what has been seen historically. In fact, it has been shown that currently circulating strains are significantly different than historical isolates5. It is important to remember when vesicular disease is suspected (e.g. lameness, snout and/or coronary bands lesions), the farm veterinarian and state/federal officials should be contacted immediately (before any further pig movements). State and federal officials will determine the next course of action. Because of the similarities to disease that are foreign animal vesicular diseases, we need to be diligent to test these cases and make sure they are associated with SVA and not one of these other vesicular diseases.

1. Singh K, Corner S, Clark S, Scherba G, Fredrickson R. Seneca Valley Virus and Vesicular Lesions in a Pig with Idiopathic Vesicular Disease. Journal of Veterinary Science & Technology. 2012;3(123):1-3. Epub Sep 4, 2012. doi: doi: 10.4172/2157-7579.1000123.

2. Knowles N, Hales L, Jones B, Landgraf J, House J, Skele K, et al., editors. Epidemiology of Seneca Valley virus: identification and characterization of isolates from pigs in the United States. Northern Lights EUROPIC 2006: XIVth Meeting of the European Study Group on the Molecular Biology of Picornaviruses; 2006 26th November-1st December 2006.; Saariselkä, Inari, Finland.

3. Linhares D, Rademacher C, Vannucci F, Barcellos D, editors. Seneca-Associated Diseases- Clinical Presentation and Epidemiological Distribution. Allen D Leman Swine Conference; 2015; St Paul, MN: University of Minnesota.

4. Vannucci FA, Linhares DC, Barcellos DE, Lam HC, Collins J, Marthaler D. Identification and Complete Genome of Seneca Valley Virus in Vesicular Fluid and Sera of Pigs Affected with Idiopathic Vesicular Disease, Brazil. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2015. doi: 10.1111/tbed.12410. PubMed PMID: 26347296.

5. Zhang J, Piñeyro P, Chen Q, Zheng Y, Li G, Rademacher C, et al. Full-Length Genome Sequences of Senecavirus A from Recent Idiopathic Vesicular Disease Outbreaks in United States Swine. Genome Announc. 2015;3(6):2. doi: doi:10.1128/genomeA.01270-15.

You May Also Like