Passionate about saving piglets

More about the people than the pigs.

Hog producers have barns full of opportunity as the number of pigs born per sow per year continues to rise year over year, but that doesn't necessarily correlate to getting the pigs weaned and out the door to grow-finish units.

Larry Coleman, a veterinarian from Broken Bow, Neb., has experienced this growth in the number of pigs born per sow and says, "It's unbelievable. But in my career, the amount of pigs that are presented on Day 1 has doubled. That's an amazing statistic that the sow is now having almost double the pigs that she did when I started practice in 1980."

But then, Coleman asks, "How do we get people engaged in the process of saving babies?"

He explained during the 2019 Allen D. Leman Swine Conference in St. Paul that there are basically two types of farms: those that save 75% of piglets, about the North American average; and those that have 90% pig survival. That 15% survival swing can equate to millions of pigs, even though Coleman says these farms have similar opportunities for piglet survival.

Breaking down his numbers, Coleman suggests that the average farm (75% survival) might lose 10% during birthing and 15% preweaning, reaching that livability of 75%, "or we can say a wastage of 25%."

On the other hand, the top 10% farms may have a 3% loss during birthing and only have a 7% preweaning mortality. "That's how I come up with my 90% livability," he says.

Circle of caring

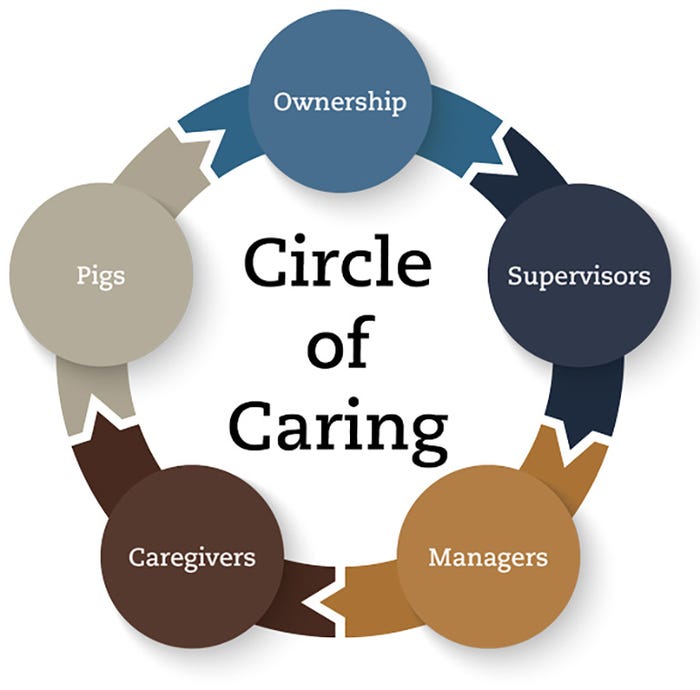

Coleman has long espoused the value of the caregiver, particularly for Day 1 care. To illustrate that importance, he uses a "Circle of Caring" diagram, but his diagram includes more than just the caregiver and the pigs themselves.

"We tend to think that piglet survival is related to the care that caregivers give pigs. But I think that's shortsighted," he says. "The circle is actually much bigger, because we have ownership here who has responsibilities. They're the ones that provide the facilities, some of the staffing, budgets, etc. They're in charge of sometimes spending money to eliminate disease. …

"Then we have supervisory people. Their jobs are largely to take care of the people in the chain — maybe organizational and training responsibilities — but these two positions are largely people in nature."

Of course, Coleman's Circle of Caring continues to flow, from ownership to supervisors to managers to the caregivers, and ultimately, to the pigs. "It's always interesting to me that the pigs have a responsibility, too; because if they don't take care of the owners with profits, the owners suffer problems."

With each piece of that circle as necessary as the next in the need to keep it revolving smoothly, the entire chain must work together to save pigs, even though sows may be having more than 20 piglets per litter. "The art or the strategy of saving babies is intuitive and repetitive," he says.

"I would suggest that it's intuitive that a baby needs to be born timely. It's intuitive that they need to stay warm, that they need to get milk and they need to have milk, every day.

"So, really, the things that the baby needs aren't very complicated. People understand that, and they can be easily trained on an individual pig to do those things."

Coleman suggests that saving babies is also repetitive, explaining that new employees on their first day of work will take care of 10 sows and deliver 150 babies. "If you add that up for a few months or a year, they're literally delivering thousands of moms and tens of thousands of babies," he says.

Caregivers get lots of reps on learning how to take care of babies. So, if strategy is not the problem, why does the average U.S. farm have the 75% survivability rate?

In other words, Coleman says having a "sense of urgency" is key. Just as when a human baby is born, there needs to be a sense of urgency when a litter of piglets is born. There needs to be urgency in seeing that the piglets are born, that they ingest colostrum, are dried off and warmed, all in a timely manner.

Don't let urgency become complacency

Coleman fears that this sense of urgency may be replaced by complacency, because "it's really hard for people to maintain a sense of urgency, because essentially, this urgency has to be carried out on a 24-hour basis.

"So, I would suggest that when we're looking at problems, the No. 1 thing that I look for — is there a sense of urgency about taking care of babies, or is there a sense of complacency? And I think most of the time, that's where you'll find the problem."

Just as the Circle of Caring is an eternal flow involving ownership, supervisors, managers, caregivers and pigs, Coleman also presents identical flows for a "Circle of Complacency" and a "Circle of Urgency."

"Ownership can become very complacent about piglet survival if they've had a high preweaning mortality for years and years and years, and they've come to expect that," he says. "They've had lots of initiatives to try to fix that. It's failed. And so, over time, they develop a sense of complacency. Supervisors, managers copy it. So do caregivers."

Control what you can — yourself

Coleman all too often sees low piglet survival becoming a chronic problem on farms, so how can farms move from the 75% survival rate to the 90% survival rate? He has worked with production systems in his career to help them become a 90% survival farm by controlling the one thing that he can control — himself.

"I can't control the owners, the managers, the supervisors, their caregivers," he says. To be an agent of change on a farm, Coleman says individuals need to be passionate about what they do; and in this case, they need to be passionate about saving piglets.

As a herd veterinarian, Coleman sees other qualities that can aid a farm in lowering prewean mortality.

Be useful. "We may not be able to fix this problem, but we can always be useful to the farm. And that's how you get credibility; to help a farm with piglet survival is on a weekly, on a yearly, on a career basis. You bring your usefulness to the farm."

Be a lobbyist. "I have never gotten tired of lobbying for the needs of a pig. When I see a cold pig, I complain about it. When I see a hungry pig, I mention it. As we all know, pigs can't talk. … At the very least, I can communicate for the pigs."

Be a copycat. "I've never been a very good researcher, but I think I'm pretty good at applying research. … I can be a bird dog on when I think someone has achieved success, and if they have success, I'd like to find out why. … I think I spent about 20 years figuring out what I thought was a good comfort zone for a piglet.

"And a few years ago, I wrote an article about 10 important points; but as I thought about those 10 points, I essentially stole them from 10 other people. So, you've got to copy success, and, I think, not be a lone ranger out there."

Be simple. Coleman wants to be remembered as a teacher, and he sees the primary job of a teacher as simplifying things. "I've got my piglet survival down to four points. I want this all done by 24 hours. I want the pig to be born unstressed. I want him to get colostrum. I want him to be in a good family, and I want him to be in a good home.

And I really don't care how you do this — but when I'm on your farm, I'm going to be asking you a thousand questions in these four areas, about whether you've thought through how you're going to accomplish this on the farm."

Yes, pig production is key to the success of any and all farms, but Coleman says that success is more dependent on the people who work the farms.

"If you're going to make changes in this Circle of Caring, you've got to be good with people," he says. "I'm sorry, if you're not good with people, I don't believe you can help a farm with piglet survival."

Coleman suggests that to be a successful people person, one should have general people skills.

Be authentic.

Admit your mistakes.

Smile.

Ask questions and listen.

Use names.

Praise and encourage.

Don't condemn or argue.

Communicate.

"You've got to realize that the problem is largely about the people," he says. "Ultimately, you don't need to do this Day 1 as a new person to the farm; but eventually, you need to know where you want to take a farm."

It is important to create a vision for a farm, and Coleman implores each fellow practitioner to become "a disciple maker.

"Now, that maybe is a little bit foreign term; but if you think about it, you're going to go to a farm a few hours a month at the very best — maybe once a month, maybe twice a month. You need to create, help create someone that's as passionate about saving babies as you are."

Coleman stresses that once you have molded someone into sharing your pig-caring passion, your work has only started.

"You can't just create somebody and then walk away to a different farm. This is actually a lifetime," he says. "Caregivers — they need lifetime coaching. Why else do we have coaches for sports teams?"

And just as sports teams keep score, Coleman says it is important that farms hold their staff accountable by tracking and reporting production numbers. He asks that his farm managers send their weekly results to him, which he then circulates to other farms.

Why does he do that? "Why do kids come and show their report cards to their parents? Kids want their parents to know how they're doing," he says, "and I think the same way, when you build influence with farms, and you ask for their numbers on a weekly basis, it becomes a time of almost celebration when they can turn in their numbers.

"Ultimately, what you're trying to do is to get the farm to please you, and to turn in good numbers."

By pleasing your herd veterinarian (or anyone in a supervisory role) with solid production numbers, you're stepping up to save piglets, who will reward the ownership, thus completing the Circle of Caring.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like