One flu, many colors

Researchers and health professionals have tried to address the virus of each host separately, ignoring the fact that influenza A viruses have a single natural reservoir or source, wild waterfowl.

June 27, 2016

Influenza A viruses have three main hosts — birds, humans and swine. In these hosts, infection can result in significant disease.

For many years, influenza researchers and health professionals have tried to address the virus of each host separately, ignoring the fact that influenza A viruses have a single natural reservoir or source, wild waterfowl. Having a single natural source or ancestor means that the core viral genes, namely the matrix and nucleoprotein genes, the genes that define an influenza A virus as indeed a type A virus, are highly conserved.

Only in the last 10 years has a “one flu” or “flu is flu” strategy been endorsed, thanks to the One Health movement. So finally, after the 2009 H1N1 global pandemic and the 2014-15 highly pathogenic H5N1 avian influenza outbreak, the most devastating animal disease outbreak in the recent history of the United States, the USDA National Animal Health Laboratory Network of veterinary diagnostic laboratories have updated their influenza A virus test into one polymerase chain reaction test for the detection of influenza A virus in pigs, birds, horses, dogs, cats or marine mammals.

The influenza A virus screening PCR test used for humans in the United States is also based on similar technology. How simple and great is that?

It’s wonderful in the sense that with one test, a sample can be detected as influenza A virus positive or not. It also helps us not to miss cases where swine are infected with human viruses or bird viruses. It is important to remember that pigs are exquisitely susceptibility to IAV strains from these two other common host species, humans and birds.

That’s where the one flu concept is too simple, because when a pig gets infected with influenza A viruses from humans and birds and other pigs, then the influenza A viruses change and become quite diverse with many variations coming out of that same core virus of long ago. The many variants of influenza A viruses paint a complicated picture, sometimes with colors too numerous to grasp with quick glances, so in-depth studies of the viruses in pigs are necessary to find answers to the problems created by influenza infections.

The in-depth studies really took off with the advent of virus characterization tools such as genetic sequencing. As a result of the numerous virus characterization efforts undertaken by U.S. pork producers, U.S. swine veterinarians, NAHLN Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratories and the USDA, the diversity, or many colors, of influenza A viruses of swine is more clearly understood. The USDA influenza A virus swine surveillance program activities between October 2011 and October 2015 included more than 90,000 samples.

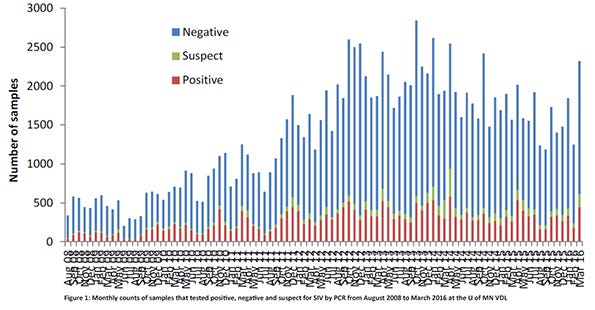

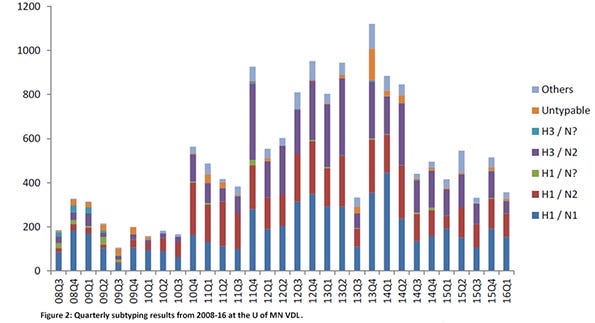

A major contributor of accessions was the University of Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory. Influenza A virus PCR positive results from the U of MN VDL were present in all months of the year, with April and October having the highest number of positive accessions (Figure 1). The most common subtypes found were H1N1, H3N2, H1N2 and H3N1 (Figure 2). While these two figures show the many “colors” of influenza A viruses of swine, the genetic characterizations of the viruses reveal even more numerous hues.

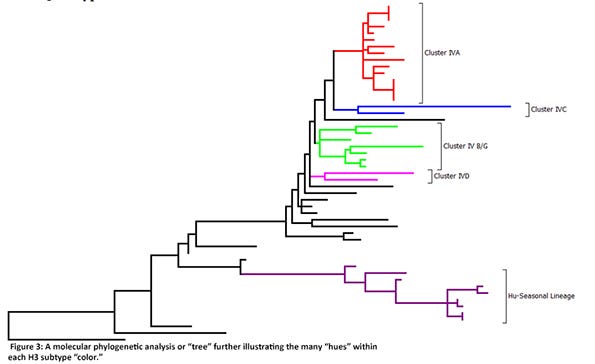

Globally, there are three lineages of influenza A viruses and these should be no surprise — they are those of the three main host species: swine, avian and human. However, in the United States, influenza A viruses of swine are either of the swine or human lineages. Of the influenza A viruses of swine in the U.S. swine H1 lineage, there are four clusters — alpha, beta, gamma and pandemic. The gamma H1 cluster dominates. Of the influenza A viruses of swine in the human lineage, there are four clusters (or “hues”) — delta 1, delta 1a, delta 1b and delta 2, and the delta 1 cluster dominates. Within the swine H3 lineage, the cluster IVA is predominant nationally, but five other clusters are also detected. Human-seasonal H3 clusters of H3N2 and H3N1 viruses also circulate in U.S. swine, representing another spillover event from humans-swine (Figure 3).

Therefore, whenever an influenza A virus is detected by the “one flu” test, it is just as important to further characterize the virus to determine the “colors,” which reveal the likely origin, lineage, possible transmission route and evolution of the virus. Influenza A viruses are fascinating, challenging and dynamic. The molecular tools now available are finally able to shed some light on this simple origin virus that becomes more complex in the pig host.

Detailed information from producer-driven and national surveillance systems should facilitate response and recovery to disease caused by influenza A virus infections.

You May Also Like