Invest in pig health and get a big ROI

Narrow profit margins often fuel hog farmers to sharpen their pencils on expenses and consider belt-tightening on certain management practices to keep the operation on the positive side of the balance sheet. However, staying proactive during a downturn in the market can keep cutbacks from financially draining a hog farm’s profit in the long run.

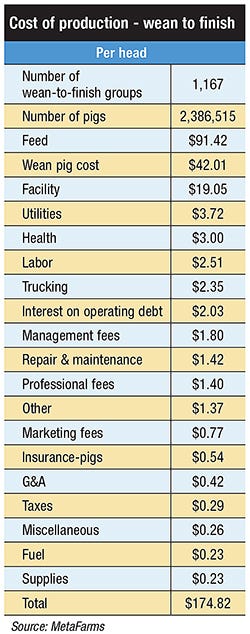

Consider the cost of production for a wean-to-finish operation. Data released from MetaFarms shows feed, weaning costs, facility costs, utilities and health costs are the top five expenses.

“The majority of the cost — feed, facility and wean costs — are already baked in the cake the day the pig shows up,” says Bill Hollis, DVM, Carthage Veterinary Service Ltd. “There are many things we can do to help that pig be profitable based on some of the decisions we make leading up to that point and some of the decisions we make to protect the pig from wean through finish.”

As a hog producer, it is important to focus on key areas that can be controlled — wean pig flow, facilities, feed processing, feed program implementation and health. In general, increasing the number of pigs that reach the finish line reduces the overall expenses per pig.

For the weaning cost side of the equation, health, age and throughput are all essential management decisions.

Investing in the health of the piglet at the sow farm can establish its solid well-being to enhance future growth performance. It is just as important to consider the most favorable age for cost and throughput to move piglets out of the sow farm.

The producer can also take a proactive approach in preparing the facility to reduce health risks. A simple “white-glove” inspection prior to a pig entering the barn can be a good tool to avoid future issues.

“It seems simple to do, but it is hard to pull off in a very busy system with pig flow, with pig supply and a great deal of pressure put on by throughput,” Hollis says. “Throughput is an important metric, but throughput at the risk of biosecurity is not a way to keep producers profitable.”

In the field, he adds, a checks-and-balances system works well to ensure team members follow through with proper cleaning practices. The goal is to have another team member besides the person who cleaned the barn perform the white-glove inspection.

Facility costs can amount to 10% of the total costs. Several decisions can assist the producer to optimize profits. Reducing the time the barn is empty and keeping it adequately filled with healthy, productive pigs can also maximize the throughput system of an operation. However, Hollis says it is important to maintain the ideal number of pigs that can comfortably be placed in the space allocated in order to foster efficient growth. So, filling the empty space of the facility only pays off if there is room for the extra pigs in the next facility. If in four weeks the barn is overstocked, it could impede growth.

In the barn, hog farmers can control feeder adjustment, particle size of the feed and the quality of feed upon arrival and during storage. Similarly, properly implementing the feed program, avoiding feed outage, routinely monitoring feed records and making proper adjustments to stay within budget can all help producers stay in the black.

Health costs, ROI

Be that as it may, decisions on the three big expenses for the most part have already been made prior to the pig arriving at the facility, Hollis states. Although preventive costs for health account for approximately 1.7% of total costs, it can positively or negatively impact profitability.

Studying calculations from Steve Pollman, a pork industry consultant, Hollis illustrates that a 2.2% decrease in finishing mortality can yield a saving equivalent of lowering corn costs by 25 cents a bushel and soybean meal costs by $20 per ton.

The cost of disease outbreak is really unknown and a figure that cannot be estimated in a budget, Hollis says. Not only can an investment in prevention lessen the drag on profits through feed efficiency and lower morality, but it also can reduce the impact of a disease outbreak.

For example, Hollis shares the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome outbreak that occurred on the farm of one of his clients. On this particular farm, he explains, approximately 25% of the pigs were PRRS-positive. As expected, death loss and cull rates increased while average daily gain and feed-to-gain ratio decreased. When they compared production records of the negative pigs to positive on these four metrics, they found a cost of $11 per pig due to a PRRS outbreak.

Taking the example a step further, he explains the extended impact of a PRRS outbreak over the next 12 months for the same operation. For this farm, a new group — comprised of 200,000 pigs — was introduced to the barn every week. Additionally, there was no pre-emptive decision to get ahead of PRRS with a vaccination program since the sow farm was naïve to PRRS. As a result, unpredictable spikes in mortality due to PRRS occurred in different groups at random times from growing to finishing. Hollis says the pain of outbreaks became so severe that the farm was motivated to implement a vaccine program. While vaccination was not perfect, it did diminish the spikes.

Furthermore, Hollis says based on lessons learned in the Carthage system, the best return on investment is striving for a PRRS-free sow herd. Looking at the economics, a PRRS infection is the most costly at the sow level with a profit loss of $7.31 per pig as a result of a trickle-down effect.

In managing health costs, it is important to acknowledge that the costs of multiple diseases can make problems even worse. Since the immune system cannot effectively fight both diseases at the same time, the costs are magnified. For instance, if PRRS costs $5.57 and influenza costs $3.23, the true cost of a pig battling both PRRS and influenza is $10.41. So, Hollis advises, producers should gain control of common swine diseases — PRRS, influenza, mycoplasma hyorhinis — with individual strategies to minimize the piling on of diseases.

Healthy pigs gain more pounds on less feed. Overall, Hollis concludes a small investment of $3 per head in disease prevention is far more affordable than the extra costs that are occurred in battling disease or multiple diseases.

Managing proactively in a weak market

Focus on top three costs

Feed

Weaning pig

Facility

Within the top three costs, focus on:

Livability

Vaccination

Diagnostics

Growth rate

Feeder adjustments

Particle size

Feed interruptions

Number weaned

Maximum sow farm efficiencies

Wean age

Throughput of finisher barns — space costs

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like