Efficiency starts with the sow

In a low-cost environment, it is important to get the optimal number of pigs to the market at the right weight.

At the close of 2015, the hog business found itself at a familiar intersection of a lower market cycle� and relatively cheap grain costs fueling an incentive to accelerate pigs’ market weights.

This time, however, the production road is paved with a higher level of sow productivity industry wide, which will bring lots of pigs and pounds of pork to market over the next 18 months. From a marketing perspective, 2016 could be an ugly year, warns Jim Lowe, D.V.M., Integrated Food Animal Medicine Systems at the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Illinois. This year, more than ever, it will be crucial to construct a roadmap that guides efficiency to minimize costs and boost profits.

When all’s said and done, pig farming is about selling meat. “We do not sell sows. We do not sell weaned pigs. We do not sell feeder pigs. We sell 212-pound carcasses,” said Lowe, speaking at the Midwest Pork Conference. “Do not forget everything before that carcass is just a cost center.”

He stressed the only things that matter are how many pigs hang on the rail and what they weigh. In a low-cost environment, it is important to get the optimal number of pigs to the market at the right weight. Lowe added this year it will be essential for more than one-third of the farm’s market hogs to hit the high-end of the packer matrix. Measuring fixed expenses, a 250-pound hog in comparison to a 300-pound hog will cost 20% more to produce at the same price.

Looking back, past rough roads have taught hog producers that improving efficiencies will always be under construction, but one important place to start is with the sow.

“A sow farm is a cost center. It accrues costs. It does not create value or profit in the global chain,” Lowe said. At the end of the day, a sow farm needs to minimize costs by producing the specified number of pigs per unit of time of the specified quality at the least cost. In order to create an efficient sow farm, decisions must be made in that sequence.

Right number at the right time

The number of pigs is fundamental to the production chain success, Lowe further explained. Pig numbers should match the size of the finishing batch. Success is dependent on feeding the production system at the exact rate all the time throughout the year. Many operations will focus on only the annual pigs-weaned-per-week average. However, if the same number of pigs is not weaned each week, the hog farm will leave money on the table.

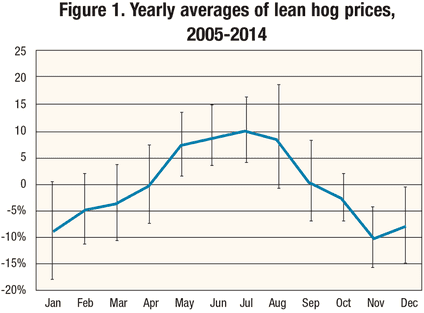

Lowe shared this example: If the hog farm’s goal is to average 1,000 pigs per week and this average is accomplished by weaning 1,200 pigs per week April to June and 800 pigs per week October to December, then the farm will be down 4% in revenue, or $6 a pig, at the end of the year, based on the normal market price cycle (see Figure 1).

Lowe shared this example: If the hog farm’s goal is to average 1,000 pigs per week and this average is accomplished by weaning 1,200 pigs per week April to June and 800 pigs per week October to December, then the farm will be down 4% in revenue, or $6 a pig, at the end of the year, based on the normal market price cycle (see Figure 1).

In order to optimize marketing opportunity, it is important to deliver the precise number of pigs at the right time. The keys to driving the right number of pigs out of the unit are:

Farrowing rate. Farrowing rate is not about how the sow is bred. It is about which sow to breed. “If you have a farrowing rate problem, you have a culling problem,” Lowe said.

Farrow target. Focusing on breeding targets and not farrow targets is a fool’s chase, he emphasized. It is a waste of resources and barn space if at the time of breeding a sow is bred that you know will not farrow.

Gilts, gilts, gilts. The quality of gilts, not the quantity of gilts, is a large part of reaching success. Acclimating gilts young is the key, and the process should begin at weaning. Lowe said this includes exposing the gilts to all the “farm bugs” long before they come in heat. This will ensure the gilts will eat consistently and gain properly to reach the target weight of 300 pounds at breeding time.

Understand what creates value in the wean-to-market site. The number of weaned pigs cannot be larger than the wean-to-market barn capacity allotted. If grow-to-finish barn capacity is 1,000 pigs and 1,200 pigs are weaned, then 200 pigs have to be housed somewhere. Sending pigs to market too soon to make room for 200 extra pigs can drain resources. Likewise, overcrowding a barn can limit gain. This scenario can also increase the mixing of pigs, which can be a recipe for disaster.

Lowe said one way to accomplish sizing the system to wean the right number of pigs consistently,

even at the least reproductively efficient time of the year, entails targeting farrowing. This management practice would include breeding more sows in the historical least reproductive period (typically the summer) to wean the target 1,000 pigs a week. Likewise, in the more efficient breeding time periods, it may mean leaving some gestation crates empty since the sows will produce larger litters, reaching 1,000 pigs with fewer sows. Lowe recognized that this concept is not a favorite among hog farmers.

Still, he stressed that variation is an efficiency killer. While the age of the pig at weaning is an individual farm’s decision, different ages of weaned pigs within a finishing unit can be a drag on efficiency. Reducing age variation starts with farrowing rate. “The sow farm controls this. I cannot control weaning-age variation at weaning. I have to control it when I start the process, which is at breeding,” Lowe said.

Quality pigs

Equally important to the production chain success is the quality of pigs. Lowe said it is essential to remember “genetics sets the ceiling.” Despite the chosen genetic package, most genetic companies are improving sow productivity on the average by 1% each year. If the sow herd is six years behind in genetics, the sows are 6% behind in feed efficiency. He pointed out that the sow accounts for half of the growth efficiency of a finishing pig. “Keeping the genetic lag tightest is the biggest deal in terms of managing genetics. Understanding the variations within a given genetic line is critical to optimize the value of the lines that you have chosen. Managing that as farm manager is one of the most important decisions you can make,” Lowe said.

Furthermore, “if genetics sets the ceiling, health allows you to touch the ceiling,” Lowe stressed. “If health is terrible, you cannot achieve the genetic potential of those animals.”

While a farm can do many things to build the sow herd immunity, it is just as important to prevent pigs from becoming ill or worse — a mortality statistic after weaning. In general, it is less costly to lose a pig at 3 days of age than any time after weaning.

Another factor impacting the quality of pigs is the movement of pigs. Among the numerous things porcine epidemic diarrhea virus taught the industry is pigs do not have to be moved multiple times, including the practice of cross-fostering pigs. Pigs can become infected, but do not show disease, while still nursing on the sow. The more the pig is moved in the farrowing house, the more likely it will become contaminated with a pathogen in the unit. Lowe explained that farms with PEDV outbreak improve farrowing morality rate by 12% to 14% by simply not moving pigs. “Being able to manage these units all-in and all-out by space needs to start at farrowing if I am going to be effective in managing that health downstream,” Lowe added.

In addition, PEDV also proved sows can wean 16 to 17 pigs well. Colostrum is important to the health of piglets. “Colostrum is not about antibodies. Colostrum is about energy. If I get adequate energy into them in the first 24 hours, really the first five to six hours, they do not burn brown fat, and their immune systems stay together. Guess what? They do quite well,” Lowe said. “Low-energy pigs end up with no immune systems and end up dying of secondary diseases.”

When all’s said and done, pigs per sow per year drives this cost bucket, Lowe pointed out. It only matters in terms that it dilutes all the fixed costs. In order to lower cost of the weaned pigs, the farm must produce more pigs out of the same number of sows. Assuming the weaned pig cost for the farm is $40, a 5% increase in pigs from a 5% increase in sows will equal 35 cents per pig in savings. Taking that scenario further, if the farm can produce the same number of pigs with 5% fewer sows, the savings is $1.65 per pig.

Forward-thinking strategy

Clearly, lower expected profit margin for hog farms in 2016 should have all farms investigating how to drive down the cost of the weaned pig. Lowe said moving forward the strategy should be centered around reducing feed usage, closely managing feed costs, properly managing gilts and optimizing farm labor.

Managing feed costs by utilizing alternative feedstuffs without sacrificing nutrition is something the animal nutritionists handle quite well, Lowe added. Nevertheless, feed usage is an area that

needs more focus. The most important thing is to get sows to eat during lactation.

“Sows will tolerate full feed from day 1. If you do not have automated sows feeders in front of sows today, giving them access to full feed all the time, you are giving up lots of pounds of weaned pigs,” Lowe said.

Moreover, proper body conditions for sows and gilts will only enhance performance. It is imperative to not over- or underfeed sows. He warned that underfeeding breeding females often happens in downturn years. Nonproductive sows that do not come into heat by day 6 or 7, abort, pregnancy-check negative or have negative returns need to leave the farm immediately.

One large margin of error for most hog farms is gilt efficiency. If the cost of a gilt entering farrowing is $10 higher, then the weaned pig cost meter is raised by 30 cents. “Driving up gilt costs is a big deal. The biggest criminal is age and weight at breeding,” Lowe said. “There is a reason we like gilts to grow like weeds and get them bred at 300 pounds at less than 200 days of age.”

Heavier gilts and those that breed beyond 200 days add to weaned pig costs in $20 increments. He advised sticking to a basic gilt feeding plan that includes growing them like a finishing hog until 220 pounds and then moving them to 12 to 14 square feet per animal. The gilts are fed calcium-phosphorus diets and not supplemented with sow vitamin trace mineral packs until closer to breeding time. Once the gilt enters the breeding herd, she needs to be bred within a 30-day window. At day 31 if that gilt is not bred, she needs to be loaded on a cull truck. Finally, if the gilt is bred, she needs to farrow.

In conclusion, Lowe listed three take-home messages for proper gilt management:

Selection

Remember, legs do not get better with age. If the gilt has structural problems at 260 pounds, it is only going to get uglier.

Driving the correct number of pigs at the right time begins with selecting the right number of females to breed.

Facilities

Gilts need room to move with a space of 12 to 14 square feet.

Gilts should not be mixed.

Gilts need to eat. If gilts are knocked off feed due to vaccinations or other management practices, their reproductive performance will be delayed.

People

The best person on the farm needs to be working with the gilts.

Anyone can breed sows, but the best artificial insemination technicians need to breed the gilts.

As one of the largest cost buckets, farm labor should always be on the top of the priority list. Optimizing farm labor is about fully evaluating the routine practices on the farm. “Are all tasks you are doing creating pigs?” is a question Lowe said every hog producer should ponder. Regularly ask if a task generates pigs or is it just the way it always has been done. However, Lowe warned eliminating or changing routine practices should not be taken to extreme. It is not about just removing unpleasant but necessary tasks like power-washing facilities. This discussion should be about assessing how you move sows at gestation, how you load farrowing rooms and how you organize the day.

“I have never been on a farm that we could not strip some labor hours out to make the day more efficient. The side benefit of this is your people are much happier when we make that happen,” Lowe said.

Another way to boost efficiency among employees is minimizing staff turnover. A high rate of employee turnover equals many hours of training for management staff. Taking this back to the sow, switching to weaning once a week will reduce the number of employees needed. Essentially, this practice can allow those employees who are excellent at breeding sows and gilts to spend more time handling that mission.

Veterinarian Jim Lowe says, “Colostrum is not about antibodies. Colostrum is about energy. Low-energy pigs end up with no immune systems and end up dying of secondary diseases.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like