Understanding sow mortality to get to root causes

Part 1: Decision regarding cause of death involves several aspects such as the recorder's training, knowledge and availability of supporting data for such diagnosis.

November 10, 2020

Sow mortality has been a growing concern over the past decade. Studies have shown that the majority of deaths occur the week before and during the first three weeks after farrowing (Deen and Xue, 1999; Sasaki and Koketsu, 2008). Also, mortality tends to increase during summer (Chagnon et al., 1991; Deen and Xue, 1999).

Recently we studied a decade of PigChamp herd performance records from four commercial farms to describe relationships in sow mortality. The farms had an average herd size of 3,700 for Farm 1; 2,437 for Farm 2; 2,505 for Farm 3; and 5,442 for Farm 4. We assessed over 350,000 PigChamp service records corresponding to 85,608 sows of which 11,852 died.

Deaths occurred at a median of 116 days (Interquartile range: 94 to 125) from last service, or 26 days (IQR: five to 103) post-partum. The distribution of deaths had two peaks, with the highest peak at one to 10 days post-partum followed by a much smaller peak at 131 to 140 days from last farrow. The second peak in mortality is likely representative of deaths that occurred during the prepartum phase of potentially unrecorded services or nonproductive sows that were unnecessarily kept in the herd.

Additionally, the median parity upon death was 2 (IQR: 1 to 4 ), with 12.5% of all deaths recorded comprising of sows that never farrowed and a subsequent periparturient risk peaking after the first farrowing with over 20% of the deaths comprising sows that farrowed only once.

Authors' experience suggest that the losses of younger females are common and are a factor that hinder cost-competiveness of the sow farm operation, as female break-even cost is typically at or after their third litter.

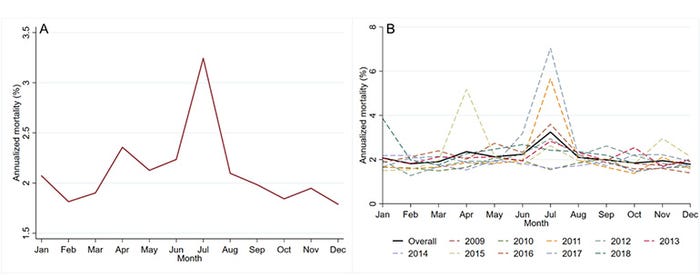

The average annualized mortality per month represents the average percent mortality in 12 months if all deaths that occurred in a given month among the four farms regardless of year remained fixed throughout the course of one year. It ranged from 1.79% to 3.29% for all farms combined (Figure 1A). A higher mortality peak was observed in July (summer) as previously reported in the literature, but we also observed a smaller peak during April (spring). The spring peak was explained by a higher mortality in 2015 that was not observed in other years (Figure 1B).

Similarly, the magnitude of the summer peak in mortality was not consistently high throughout the years, some years even presenting no peak at all during summer months. This was also evidenced when looking at mortality at the farm level. A higher mortality during warmer months is likely related to factors aggravating thermal stress (D'Allaire et al., 1996), in which case management practices such as higher ventilation and cooling can translate to lower mortality. Those factors can potentially explain why mortality is so high in some summers but not in others. However, to truly assess that association, further investigations on the actual barn temperatures and humidity and interventions in relation to monthly mortality are needed as it is data that unfortunately are not routinely recorded in most farms.

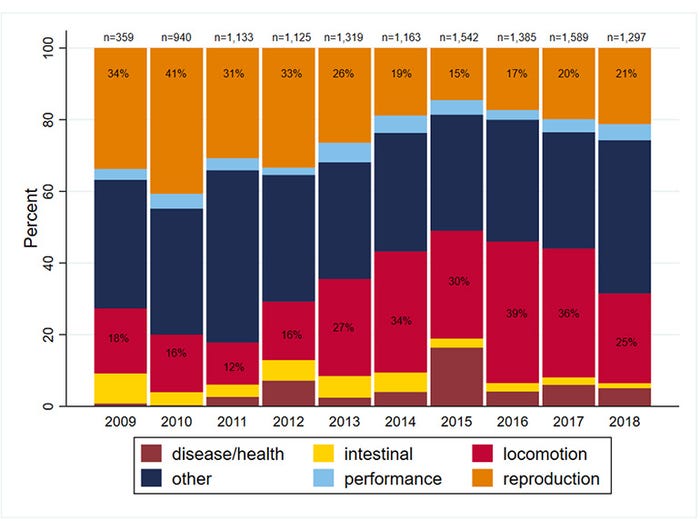

We also classified removal reasons among deaths into six categories as previously described by Ketchem et al. Overall, the main reasons for death were locomotion (n=3,190; 27%) and reproduction (n=2,846; 24%), with disease/health, intestinal and performance reasons each accounting for less than 6% of all deaths. Of course, these proportions were not consistent throughout the years, with reproduction reasons decreasing from 34% to 21% and locomotion reasons increasing from 18% to 25% in 2009 and 2018, respectively (Figure 2).

We also looked at percent of death removals due to pelvic organ prolapse over the years. This percentage fluctuated between 4% and 13% and, although it had been consistently increasing during 2015-16, it is still within the range of the observed in the previous years. Of note, overall, 36% of the deaths were classified as due to "other reason," which included unknowns, depopulations and behavior problems, among others.

Other than completion often being an issue with retrospective studies using production records, the decision regarding cause of death involves several aspects such as the recorder's training, knowledge and availability of supporting data for such diagnosis. Thus, these limitations must be considered when describing sow mortality.

For Part 2 of this article, we will explore environmental, farm-level and individual-level factors possibly associated with sow mortality using different methodological approaches and discussing its limitations and implications.

References

Chagnon, M., D'Allaire, S., and Drolet, R. (1991). A prospective study of sow mortality in breeding herds. Canadian Journal of Veterinary Research (Revue Canadienne de Recherche Veterinaire), 55(2), 180-184.

D'Allaire, S., Drolet, R., and Brodeur, D. (1996). Sow mortality associated with high ambient temperatures. The Canadian Veterinary Journal (La Revue Veterinaire Canadienne), 37(4), 237-239.

Deen, J., and Xue, J. (1999). Sow mortality in the U.S.: An industry-wide perspective. Allen D. Leman Swine Conf.

Sasaki, Y., and Koketsu, Y. (2008). Mortality, death interval, survivals and herd factors for death in gilts and sows in commercial breeding herds. Journal of Animal Science, 86(11), 3159-3165.

Sources: Mariana Kikuti, John Deen, Cesar A. Corzo and Juan Carlos Pinilla, who are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like