Counter-Balance Hog Feed Costs with Better Risk Management Plan

Pork producers have learned some hard lessons about raising and selling hogs over the last 10 years or so. First, not that anyone needed the lesson, but 1998 taught us that losing as much as $60/head was no fun at all

April 15, 2010

Pork producers have learned some hard lessons about raising and selling hogs over the last 10 years or so.

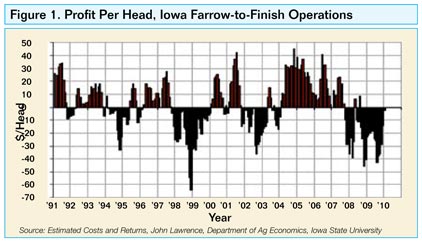

First, not that anyone needed the lesson, but 1998 taught us that losing as much as $60/head was no fun at all (Figure 1).

Second, 2008 and 2009 taught us that spending $140 to $160 to produce a pig on which the loss was as much as $40/head was even less fun!

The aftermath of pork industry profit debacles such as these is often a renewed interest in risk management. The problem is, the interest wears off rather quickly after producers initiate “too late” risk management plans, and then leave money on the table when markets recover as they did in 2000, and to a lesser degree, as they did in 2004.

Thoughts of managing risk get even rarer after profits return. And when profits stick around for a long period, such as they did from early 2004 to September 2007, some producers seem to think there's no risk at all. Then reality hits again.

Rewards for Risk-Takers

By definition, risk entails some degree of adverse consequences. But markets value risk, and in virtually every case, markets reward the acceptance of more risk with higher returns. The risk-reward tradeoff is a fundamental relationship of markets.

Avoiding risk means avoiding the extremes. Or, perhaps more accurately, avoiding the terror of losses has a consequence of accepting lower profits. Think merry-go-round or roller coaster ride. Accepting risk means reaping higher profits over time, but with some often-frightening ups and downs.

Risk management is an effort to reduce the frequency and impact of adverse results. Perfect risk management would eliminate the losses, while leaving potential gains in play — a feat seldom, if ever, accomplished.

Risk also brings rewards. Therefore, avoiding risk means foregoing some rewards. As Iowa State Extension Economist John Lawrence explains it so well, “Risk management is an effort to not sink the ship, while at the same time not missing the boat.”

Types of Risk

There are several types of risk, but only some can be managed.

Strategic risk is the fundamental risk faced by any industry. It is broad and cannot be managed well, except by diversification; that is, exposure to different sources and degrees of risk by participating in different businesses.

The packing capacity situation in 1998 and the H1N1 influenza virus situation in 2009 can be characterized as issues of strategic risk. Another example would be the impact of a foreign animal disease that affects trade. These have had — or could have — profound impacts on pork producer profits, but all are generally out of producers' control.

Counter-party risk is a larger and larger issue in the pork industry as business relationships become increasingly complex. Counter-party risk was minimal when producers were more or less stand-alone businesses that purchased inputs and sold outputs through arms-length transactions in spot markets where there were many buyers and sellers.

Contractual relationships, which are often aimed to reduce risk, make someone else's (i.e. counter-party) actions or failures a major determinant of the producers' risk profile. This risk is also difficult to manage, but carefully drafted contracts can help. Weaned pig contracts, which include feed costs as a pricing factor, are an effort to reduce counter-party risk.

Then there is price risk — the most prominent and traditional form of risk faced by pork producers. Historically, the focus of price risk management was on hog prices, and the risk posed by hog price variation is significant.

Figure 2 shows weekly Iowa-Minnesota hog prices for 1973-2009, and the average of two measures of variability for each decade. While prices certainly feel more volatile in recent years, these data indicate they are not. In fact, both the standard deviation and the coefficient of variation (the standard deviation divided by the average) are smaller for the 2000s than they were for the 1990s.

The 1990s data were heavily influenced by the very low hog prices of October-December 1998, but the average hog price, standard deviation and coefficient of variation are $61.43, 11.7 and 19.0, respectively, even when we omit those fourth-quarter 1998 prices.

Producers' tendencies to focus on hog price risk is quite understandable; until the 1990s, the vast majority of producers raised much of the grain they needed for feed and the cost of raising corn was relatively stable.

Government feedgrain programs encouraged high levels of grain production by compensating grain producers for the difference between a price based on the world market and a target price, supposedly set to cover costs and provide a profit margin. The net result of both was stable and usually low-priced grain for the livestock industry, which mitigated cost risk.

That all changed with federal biofuels programs that created a new, large user of corn by mandating and subsidizing the use of ethanol in motor fuels. The resulting rise in corn prices made government support programs moot and caused prices of soybeans (thus, soybean products) and other grains to rise to compete for resources. This activity tied corn prices to other economic variables, most notably oil prices. Cost variation that once had been of concern to livestock producers only in the event of drought or a rare flood has now become a huge concern, every day. (Also see, “Feed Challenges Reshape Pork's Cost Structure,” page 28).

Major Shift in Feed Costs

Figure 3 demonstrates this huge change in the variability of feed cost. The chart shows the value of the corn and soybean meal needed to make a standard 16% crude protein hog diet. While the cost of other ingredients is indeed variable, and some contributed to the volatility of feed costs in 2007 and 2008, the costs of corn and soybean meal capture a large part of the variation in feed expenditures.

The numbers for the pre-ethanol period of 1991 through 2006 and ethanol period of 2007 through 2009 are very different. A 50% increase in the average cost of corn and soybean meal was accompanied by a doubling of the standard deviation and a 33% rise in the coefficient of variation.

But a caveat is in order: The chosen time periods include the adjustment period between the old and new grain price paradigms. It is obvious that this index of feed costs is settling in to a new range of roughly $140 to $180/ton. If it remains in that range, the standard deviations over future time periods “could” be quite similar to the standard deviations we saw in the pre-ethanol period. I emphasize the word “could” because it is “possible,” though most observers agree it is not probable, given the tight alignment of corn usage and supply each year and the new, very high annual corn usage levels of 13 billion bushels and more.

What You Can Do

Regardless of the variation, the new level of feed costs means that more money will be at risk in the hog business, which means risk management will continue to be a hot topic.

The good news is there are weapons to help counteract risk, including:

Futures contracts on lean hogs, corn, soybean meal and, beginning April 26, distiller's dried grains with solubles (DDGS). The first three trade on the floor of the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME) Group, as well as electronically through CME Group's Globex platform. The new DDGS contract trades only on the Globex electronic platform.

All are traditional futures contracts that can be used to lock in an expected price for your output or feed ingredients. Using futures contracts still leaves you with basis risk — that is the risk that your local price might differ from the futures price by an unusual amount. But basis risk is virtually always less than price risk, thus reducing the risk you face when you hedge prices using futures. Remember, selling hog futures or buying grain futures says, in effect, “I'm satisfied with the futures prices less the historical basis.”

Options on lean hogs, corn and soybean meal futures. Options are, in essence, insurance in which you pay a premium for the right to either sell or buy a futures contract at a specified price. The option to sell a contract is called a “put.” The option to buy a contract is a “call.” The specified price is called the “strike price.” Pork producers use Lean Hogs Puts to establish a floor price for hogs and use Corn or Soybean Meal Calls to establish a ceiling price for feed ingredients.

The premiums on options are determined by the market through a bid-ask process, but they are based on three factors:

Intrinsic value

This is the difference between the strike price and the actual price of the futures contract. Options will not always have intrinsic value. If the strike price of a put is below the actual futures price, the put has no intrinsic value and is called “out of the money.” A call option with a price above the current futures price would be described the same way. A put with a strike price above the current futures price or a call with a strike price below the current futures price would have intrinsic value equal to the difference between the strike price and the price of the futures contract. They would be called “in the money” options.

Time value

The farther an option expiration date is into the future, the more time value it has. The reason is simple: The longer the time to expiration, the greater the chance that the futures price will move far enough to make the option valuable.

Volatility of the underlying futures contract

Higher volatility increases the chances that the option will have value and drives up the premium.

Most options expire worthless, meaning that the futures price never gets to a level where the option is “in the money” and is exercised. Producers usually cite this fact as evidence that options are a bad deal. My response: “Is insurance a bad deal just because the insured hog barn doesn't burn down?” Of course not. Options are the same thing — insurance against a bad economic outcome. It is a good thing if that bad outcome does not happen and you do not exercise an option. You are indeed out the option premium, but you have successfully avoided a more damaging consequence.

Cash contracts for feed ingredients or hogs. Elevators and soybean processors will contract for future deliveries at set prices or at set basis levels relative to futures prices. Packers will do the same things on hogs. Elevators and packers often specify a basis that covers the largest risk they have faced in the past, reducing the value of the contracts to producers, so producers must know historic basis levels. Elevators and packers accept margin responsibility in these types of contracts.

Cover Risks on Both Sides

The bottom line is that price risk is now critical on both sides of your business. Hog and feed ingredient prices determine your gross margin, and it is margin that pays other bills and provides profits. You need to know the margin being offered to you for all of the hog sales you plan to make over a reasonable time horizon.

Most producers frequently compute a “hog crush” that uses futures prices to predict a gross margin. The hog crush takes its name from soybean crushers' practice of using soybean, soybean oil and soybean meal prices to arrive at an expected crush margin. You can also estimate the gross margin above feed costs that your operation can generate by plugging in lean hogs, corn and soybean meal; and, when available, DDGS futures prices, your local basis levels and your diet formulations and feed consumption data. Data are available at any one time to compute the hog crush for the next year.

Historical data can be used to estimate past crush margins that can then be used to put future crush estimates into context. How many times have June futures offered a crush margin above $20/head, $30/head, $40/head? Knowing this context will help you “pull the trigger” and, hopefully, enhance profitability while reducing risk.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like