Feed Ingredient Options Add Complexity to Swine Diets

One would be hard-pressed to find anyone in the American pig industry who does not think that feeding pigs successfully is more difficult today than it was just a decade ago. The trend toward more complex feeding programs will likely continue, driven in part by the demand for corn by the biofuels sector

April 15, 2010

One would be hard-pressed to find anyone in the American pig industry who does not think that feeding pigs successfully is more difficult today than it was just a decade ago. The trend toward more complex feeding programs will likely continue, driven in part by the demand for corn by the biofuels sector.

And, there is a good chance that the biodiesel sector will expand, which will place more pressure on common feed fat sources, such as choice white grease and corn oil.

As these trends unfold, pork producers can expect generally higher feed costs and greater use of co-product feedstuffs.

The good news is that the evolution of the U.S. pig feed sector is up to the task. Many other important pork-producing countries have diversified pig diet composition for quite some time. While we may have to adjust our approach to feeding pigs, we can draw on the experiences of others.

Clearly, functions outside the science of nutrition will be essential. Greater emphasis on the use of risk management tools, reassessment of what performance and financial records to keep and how to interpret them and, perhaps, some retooling of feed manufacturing and delivery equipment will be necessary. An enhanced focus on health management vs. disease control and continued improvement in genetics will keep the U.S. pork industry competitive in the global market.

There are many nutritional approaches to maximizing net income. Following are a few areas that offer great potential for success while taking on minimal risk.

Feed the pig's gut as well as the pig.

While feeding pigs will continue to evolve, there is little likelihood of revolution. Perhaps the greatest change will be a more sophisticated approach to feeding the gut of the pig, as well as the whole pig.

For example, the bacteria, yeasts and other organisms that live in the gastrointestinal tract contribute to a pig's overall health. Currently, there is a great deal of research focusing on how to encourage the growth of favorable microorganisms and discourage the growth of pathogens. Changing ingredients in the pig's diet may help achieve this goal.

The development and use of probiotics and prebiotics may also provide positive health outcomes. This is a very difficult field because there is much to learn about the pig's gut and its function. But there is little doubt that some advancement can be expected in the next decade.

Effective use of co-product ingredients.

The use of co-product ingredients has become quite common in the U.S. swine industry. Producers who have incorporated co-products into their feeding programs most successfully have trimmed feed costs and improved net income.

If we look at diets around the world, the pig continues to demonstrate its ability to utilize a broad list of ingredients — from corn, sorghum, soybean meal and lupines, to sunflower meal, canola meal, tapioca and bakery byproducts.

Corn-soybean meal diets will remain a staple for the foreseeable future, but adoption of co-products will be essential to trim higher feed costs.

Interestingly, it is easier to successfully feed pigs with multiple co-product ingredients than it is to use just one in a diet. The law of averages suggests that inadvertent overestimation of the nutritive value of one ingredient will usually be offset by the inadvertent underestimation of another. In this way, the overall diet meets the desired nutritional specifications. This lesson was learned by the Europeans many decades ago.

No matter how it is done, success in using co-products requires accurate information on nutrient content, physical handling characteristics and the presence of any anti-nutritional factors that may lead to digestive problems or poor palatability. By starting conservatively and gradually using greater quantities of co-products, many producers have learned that success is possible and financial rewards are substantial when managed correctly.

Co-product quality assurance.

As co-product ingredients are used more aggressively, quality assurance programs will become central to success. Producers will have to decide where to spend limited dollars on incoming ingredients or outgoing mixed feeds in order to minimize feed costs, while ensuring that the nutrient requirements of the pigs are met.

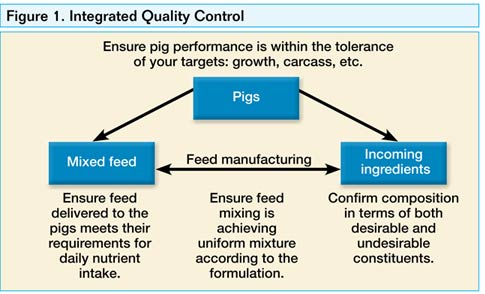

There is no hard and fast rule on where the bulk of quality assurance money should be spent. It is fair to say, however, that if testing mixed feeds shows good success in producing a consistent diet that meets but does not exceed specifications, then investment in lab assays is likely to switch more to ingredients of variable composition in order to provide the best information for feed formulation. Success in quality assurance will occur when accurate and useful information is provided by the laboratory and the information is effectively applied to the formulation and manufacturing of diets in the optimum feeding program, as diagrammed in Figure 1.

The ultimate quality assurance test is pig performance. If performance targets are met, then it is a safe bet that diets are meeting the needs of the pigs. However, achievement of performance targets offers no insight into whether or not diets are exceeding the needs of the pig.

Optimizing net income vs. maximizing pig performance.

An important part of the U.S. swine industry evolution is the ongoing switch from producing feeding programs that maximize performance to feeding programs that maximize net income. The two concepts do not necessarily go hand-in-hand.

Increasingly, pork producers are learning that pigs that grow the fastest may not be the ones that make the most money, nor does the best feed conversion translate into the best net income. Of course, some producers have very tight growth targets to achieve in order to meet the provisions of packer contracts, but if this is the case, the results will be reflected in financial returns. Therefore, animal performance information must be linked with financial returns.

It is very difficult to envision a situation where maximizing net income for the overall farming operation is not the best overall target. One implication of this approach is the need to revise the feeding program as market conditions change. For example, the optimum feeding program when market prices are high and feed costs are low may not be the optimum feeding program when market prices are low and feed costs are high.

Adherence to the feed budget.

Most feeding programs are built on a feed budget basis. In other words, specific amounts of feed are allocated per pig as it grows to market weight. The nutritionist estimates the pigs' requirements for each nutrient, for each phase of growth from weaning to market. The number and weight range for each diet phase is arbitrary and reflects such things as farm size, animal flow, feed delivery capabilities, and the goals of the producer.

Some pork producers prefer to use only a few diet phases, because it is easier to manage; others prefer many phases to reduce the overall cost of raising a pig to market. Whichever is chosen, the feed budget is a wonderful tool used not only by nutritionists to formulate diets, but also by feedmill managers to determine the quantity of feed required per delivery.

Most critically, the feed budget is a mechanism to link the feeding program to a financial budget. However, despite the most sincere attempts to provide feed to the pigs according to the feed budget, deviations are surprisingly common. It is therefore recommended that feed deliveries be recorded and the quantity of feed actually delivered per pig be calculated on this basis, and then compared to the feed budget. In other words, actual feed usage is compared to projected usage. Deviations between target and actual use are as high as $3 to $6/pig. Consequently, tracking the budget and making necessary adjustments to ensure the feed budget is being adhered to can lead to feed cost savings of $1 to $5/pig sold. It is a simple process and an excellent way to track feed costs in real time.

Pigs are adaptable.

The future still looks very bright for the American pig industry. High feed costs are often mirrored in other parts of the world due to the global nature of trade. U.S. producers have access to an excellent supporting cast of consultants, suppliers and researchers. However, the status quo will not be an acceptable business model, as rising costs in some sectors must be offset by savings elsewhere.

Because feed represents 60-80% of the cost of production, it is a logical place to seek financial rewards. The good news is the pig is a highly adaptive species with the ability to perform very well under highly different diet regimes. Our challenge will be to take advantage of the pig's inherent ability to adapt and to make adjustments in a manner that improves net income, while ensuring the production of a high-quality pork product in an environmentally sustainable manner.

Production Breakthroughs Will Drive Gains In Efficiency

As pork producers fine-tune their risk management and financial strategies, there remains the never-ending challenge to cut costs and improve production efficiencies. Doing so requires a thorough understanding of the biology and the genetics of the pig. In addition, the competition rendered by the burgeoning biofuels industry for dietary mainstays — corn and soybeans — will continue to challenge producers as they wring full value from all dietary ingredients, including the byproducts generated by those rivals.

With feed costs tethered to the price of oil and biofuels, pork producers will be called upon to redouble efforts to conserve energy and take full advantage of the rich crop nutrients generated by well-managed manure handling systems in an environmentally conscious and sustainable way.

Following is a series of four articles targeting the feed and fuel challenges that lie ahead; enhanced genetic selection methods; and a futuristic look at building, ventilation and waste management alternatives.

You May Also Like