Weigh the benefits of treating piglets’ hernias with amoxicillin

Results showed the single-dose antibiotic treatment at birth prevented umbilical defects, promoted growth and decreased mortality at 9 weeks of age, but only to a limited extent.

May 4, 2017

Editor’s note: Research article provided by Jinhyeon Yun, Satu Olkkola, Marja-Liisa Hänninen, Claudio Oliviero and Mari Heinonen, University of Helsinki, Finland

Pigs with hernias in commercial herds are usually culled or sold for a lower price, and associated with reduced growth rates and higher mortality rates than unaffected group mates. The event of scrotal and umbilical hernias is often a frustrating concern for modern swine production since these physical defects often render the pig less valuable as a market animal.

Research has shown that the frequency of hernias is 0.4% to 6.7%, but in some instances a spike in occurrences can occur. The prevalence of hernias in piglets varies according to gender, breed and environment. Porcine umbilical hernias are mainly due to incomplete closure of the umbilical cord after birth, which is caused by genetic variability in musculature of the navel cord or infection of the umbilical stump or both. Inguinal and scrotal hernias are defined by the protrusion of the hernia contents into the inguinal canal or scrotum.

Despite preventive antimicrobial treatment not being recommended in Finland, some farmers administer antimicrobials to newborn piglets in order to reduce the prevalence of umbilical infections and hernias. However, previous studies showed that administration of oxytetracycline to newborn piglets failed to reduce mortality and several diseases, except foot abscesses, until death, or had no effect on development of umbilical hernias.

In addition, Rutten-Ramos and Deen reported that administration of long-acting ceftiofur to piglets at birth did not affect hernia prevalence. Only anecdotal evidence is available regarding the effectiveness of using antimicrobials to prevent umbilical hernias, and the reports do not appear in peer-reviewed journals. However, studies on humans and pigs showed that the use of antibiotics for newborns disturbs normal development of microbiota in the gastrointestinal tract for a considerable time, and the use of antimicrobials leads to an increase in drug resistance of the normal microbiota.

Antimicrobials are used for preventing and treating diseases. However, prophylactic administration of antimicrobials directly after birth should be considered carefully. Consequently, in this study the scientists aimed to investigate the effects of a single amoxicillin treatment of newborn piglets on the prevalence of hernias and abscesses in the umbilical and inguinal areas until the age of 9 weeks. Also, the researchers investigated whether the treatment is associated with growth, mortality or the need to treat piglets for other diseases.

The research team hypothesized that a single preventive dose of amoxicillin to newborn piglets does not influence the prevalence of hernias, but it may have an effect on the need to treat piglets for other diseases, especially intestinal disorders. Finally, they aimed to determine whether amoxicillin treatment of newborn piglets increases the prevalence of aminopenicillin-resistant coliforms and characterizes the resistance patterns of fecal E. coli isolates.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted between August 2015 and July 2016 in a commercial herd of approximately 850 sows (Landrace × Yorkshire) in southern Finland. Sows and gilts (hereafter sows) were moved to a farrowing pen between three and eight days before parturition, and kept there until weaning. The pen consisted of a conventional steel farrowing crate on a half-slatted concrete floor, with the piglet shelter situated in one corner with a heat lamp on a solid concrete floor. A bucketful of sawdust was provided daily on the solid floor. Sows were allowed ad libitum access to water from a nipple drinker and were fed a standard lactation diet three times a day via an automatic dry-feeding system. A creep feeding diet (net energy 11.0 megajoules per kilogram; crude protein 19%) for the nursery piglets was provided from 14 days after birth until weaning.

The umbilical area of newborn piglets was not disinfected after birth. Umbilical cords longer than 12 centimeters were cut at that length after drying up during the first day of life. The piglets were cross-fostered to even up the litters at two days after birth at the latest. At the age of 2 to 5 days, the farm personnel routinely picked up each piglet individually for an intramuscular injection of iron, 200 milligrams, and for oral dosing of coccidiostat toltratsuril, 20 milligrams per kilograms. During the same handling, male piglets were given an intramuscular injection of meloxicam, 0.4 milligrams per kilograms (Metacam, 5 milligrams per milliliters) and castrated. The teeth of the piglets were not routinely polished, except for those noticeably biting the udders of the sow. Tails of the piglets were not docked.

Piglets were weaned at approximately 28 ± 3 days and vaccinated against circovirus about one week after weaning with 1 milliliter of intramuscular porcine circovirus vaccine. Pigs were transported to a temperature-controlled room at weaning.

Each room had 20 pens with approximately 20 to 25 pigs per pen. The pens were thoroughly cleaned, disinfected and dried before piglets were transported. Each pen had a solid concrete floor, with 25% of it slatted dung area, and was provided with three buckets of sawdust. After pigs moved in, a supplementary shovelful of sawdust per day was added on the ground if it was soiled or dissipated.

Pigs in each pen were allowed ad libitum access to water from three nipple drinkers and fed a standard weaning diet (NE 10.5 megajoules per kilogram; CP 17.5%) for 10 days, and a growing diet (NE 9.9 megajoules per kilogram; CP 16.5%) for 28 days subsequently.

A total of 480 litters, producing 7,156 piglets, were assigned to two groups during the first day after birth. The Ant (antibiotics) group, consisting of 3,661 pigs from 240 litters in six batches, was given an individually numbered green ear tag on the left ear and injected with 75 milligrams of amoxicillin in the neck muscle. The Con (control) group consisted of 3,495 pigs from the other 240 litters in six batches, and they were each given an individually numbered orange ear tag on their right ear and not treated with any routine antibiotics at birth. Cross-fostering was allowed only within the same treatment group.

At weaning, the piglets in the same treatment groups were housed in the same pens. The researchers involved in evaluations and statistical analyses were unaware of the allocation of the piglets to the different groups during the entire sampling periods and statistical analyses.

Researchers palpated the umbilical and inguinal areas of the pigs twice while the animals were standing to diagnose the presence of hernias and abscesses, approximately three (total N = 6,523) and 38 days (total N = 6,451) after weaning, i.e., at 4 and 9 weeks. The only reason for the drop in the numbers of animals included in the present study was that some animals died between birth and 9 weeks.

An umbilical hernia was determined as a discontinuity of the abdominal wall at the umbilicus with protrusion of abdominal content into a hernia sac formed by the skin and surrounding connective tissue. An inguinal hernia was defined as a condition where intestines or other abdominal organs pass into the inguinal canal through an abnormally large and patent vaginal orifice through which the vaginal process and peritoneal cavity communicate. An abscess was recorded when an enclosed collection of pus with a firm formation was palpated. The length of hernia ring as well as the diameter of the hernia and the abscess was estimated in centimeters. When both hernia and abscess were present, their joint diameter was measured.

At the same time points, i.e., 4 and 9 weeks, three pens per batch (altogether 36 pens with 408 Ant and 415 Con pigs) were consistently selected from the middle of the room and each individual pig with no defects in umbilical and inguinal areas (hereafter non-defective pigs) from the pens was weighed. Also, the bodyweights of pigs diagnosed with a hernia, abscess or both were recorded individually on the same days. Pen hygiene was evaluated by a visual inspection.

Approximately three days after weaning, in a total of 10 batches, approximately 5 grams of fresh feces were collected from three to four areas of the floor of each pen. For each sample, two typical distinct E. coli colonies (indicated by red color and bile salt precipitation halo) were picked and subcultivated on Luria Bertani agar plates (Difco, Sparks, MD) and incubated overnight. These colonies were confirmed to be E. coli.

Occurrence, size of hernias, abscesses

Out of a total of 6,523 pigs palpated at four weeks, umbilical hernias or abscesses were found from three (0.05%, [two barrows and one female]), or eight (0.1%, [two barrows and six females]) pigs, respectively. At the same time, inguinal hernias, abscesses or both were found from six (0.1%, [five barrows and one female]), 20 (0.3%, all barrows), or two (0.03%, all barrows) pigs, respectively. The occurrence ratio of umbilical or inguinal hernias, abscesses or both was not significantly different between the Ant and Con groups palpated at 4 weeks.

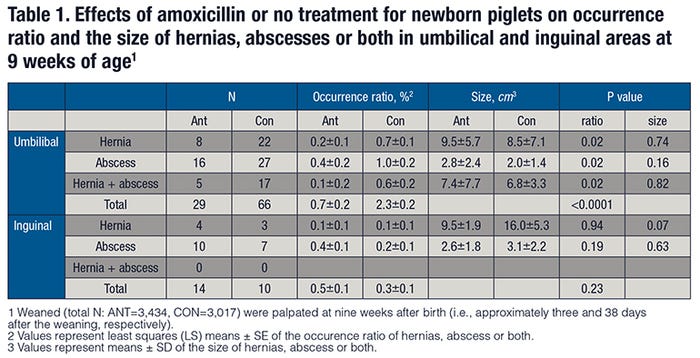

Out of a total of 6,451 pigs palpated at 9 weeks, umbilical hernias, abscesses or both were found from 30 (0.5%, [17 barrows and 13 females]), 43 (0.7%, [20 barrows and 23 females]) or 22 (0.3%, [13 barrows and nine females]) pigs, respectively. At the same time point, inguinal hernias or abscesses were found from seven (0.1%, all barrows) or 17 (0.3%, [16 barrows and one female]) pigs, respectively. The occurrence ratio of umbilical hernias, abscesses or both in the Ant groups was significantly lower than in Con groups (P < 0.05 for all, see Table 1). However, the ratio of inguinal hernias, abscesses or both was not significantly different between the Ant and Con groups at 9 weeks of age (see Table 1).

The size of umbilical and inguinal hernias, abscesses or both was not significantly different between the Ant and Con groups or between barrow and female pigs at both 4 and 9 weeks of age. Of the 39 pigs that were diagnosed with umbilical or inguinal hernias, abscesses or both at 4 weeks of age, 19 (49%) pigs still showed the same defects, while these defects were not detected from the remaining animals at 9 weeks of age.

Bodyweight and mortality

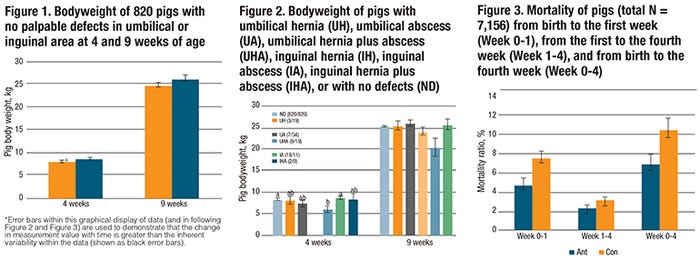

Average bodyweight measured from a total of 820 non-defective pigs was 8.2 kilograms ± 1.8 and 25.3 kilograms ± 4.6 at 4 and 9 weeks of age, respectively. The average bodyweight of 36 pigs diagnosed with hernias, abscesses or both at 4 weeks of age was 7.9 kilograms ± 2.1, and that of 88 pigs at 9 weeks of age was 25.1 kilograms ± 5.2. The treatment did not have a significant effect on bodyweights of pigs with hernias, abscesses or both at 4 or 9 weeks of age. However, the average bodyweights of non-defective pigs in the Ant groups were significantly higher than those in the Con groups at 4 or 9 weeks of age (refer to Figure 1).

The average bodyweight of pigs that had an inguinal hernia (N = 6) was lower than that of pigs with an inguinal abscess (N = 18) or non-defective pigs (N = 820) at 4 weeks of age (P < 0.05, Figure 2). However, bodyweights of pigs with different defects were not significantly different regardless of the types of hernia or abscess at 9 weeks (Figure 2).

The average daily weight gain of the non-defective pigs between weeks 4 and 9 was greater in the Ant groups (N = 405) compared with the Con groups (N = 415) (LS means ± SE; 497.5 grams per day ± 5.0 vs. 475.3 grams per day ± 4.9, P < 0.01). Mean ± SD of the average daily gain between weeks 4 and 9 in pigs was 432.1 grams per day ± 91.1 for an umbilical hernia (N = 6), 385.7 grams per day ± 210.4 for an umbilical abscess (N = 3), 361.9 grams per day ± 90.2 for an inguinal hernia (N = 6), and 460.7 grams per day ± 105.9 for an inguinal abscess (N = 4).

The piglet mortality ratios in the Con group were higher than those in the Ant group during the first week of life (LS means ± SE; 7.5% ± 0.7 versus 4.7% ± 0.7) and between birth and the fourth week (10.5% ± 1.0 versus 6.9% ± 1.0) (P < 0.05 for both, Figure 3). Two deaths out of 39 pigs with hernias, abscesses, or both at weaning occurred in the Con group during the entire experimental period.

The piglets in the Con group had a higher percentage of leg problems than the piglets in the Ant group. The occurrence ratio of pigs needing treatment for other diseases was not significantly different between Con and Ant groups during the nursing period. The most common medicine used for treating sick piglets during the nursing period in this study herd was amoxicillin.

Conclusion and discussion

The administration of amoxicillin for newborn piglets had no effect on the prevalence of hernias and abscesses in umbilical area of pigs until 4 weeks of age and in inguinal area until 9 weeks of age. However, in contrast to the scientists’ hypothesis, the treatment decreased the prevalence of umbilical hernias and abscesses at 9 weeks of age.

The amoxicillin treatment also reduced mortality and the occurrence of leg problems until weaning and increased growth of the pigs until 9 weeks of age. Also, the prevalence of umbilical hernias and need for treatments was low in the herd studied. The treatment did not have an effect on the resistance pattern of the E. coli isolates from the feces of the weaned pigs, but it is notable that a remarkable proportion of resistant and multiresistant bacteria were found in the study herd.

Contrary to the hypothesis of the study, administration of one dose of amoxicillin during the first day of life decreased the prevalence of umbilical hernias and abscesses at 9 weeks of age and the need to treat the piglets for leg problems. Moreover, the treatment increased the growth of the pigs between birth and 9 weeks of age, and decreased mortality before weaning.

However, the effects on the prevalence of umbilical hernia as well as on growth were minor compared to the workload that was involved in the treatment. On the other hand, the treatment had no effect on the prevalence of inguinal hernias and abscesses until 9 weeks of age. The size of hernias and abscesses in the umbilical area, or the need to treat the piglets for other diseases during suckling, was likewise not affected by the treatment.

Although no difference was found in the prevalence of antimicrobial-resistant intestinal coliform bacteria between the groups, the current results need to be interpreted with caution as the most likely reason lies in the presence of background resistance among intestinal coliform bacteria and E.coli. Repeated long-term antibiotic treatment of large number of piglets during their first day of life could have an additive effect promoting the selection of resistance genes at the farm.

Summarizing, these results showed that the single-dose antibiotic treatment at birth prevented umbilical defects, promoted growth and decreased mortality at 9 weeks of age, but only to a limited extent. Therefore, not enough evidence was found to support the practice of preventive use of antibiotics for newborn piglets, especially considering the possible influence on the development of the normal intestinal microbiota and the selection of antimicrobial-resistance genes at the herd level. Furthermore, the overall costs of the antimicrobial treatments are likely to exceed the observed minimal benefits.

This article was originally published: PLOS Feb. 15, 2017, see journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0172150.

You May Also Like