Study finding drug-resistant bacteria overblown

December 27, 2016

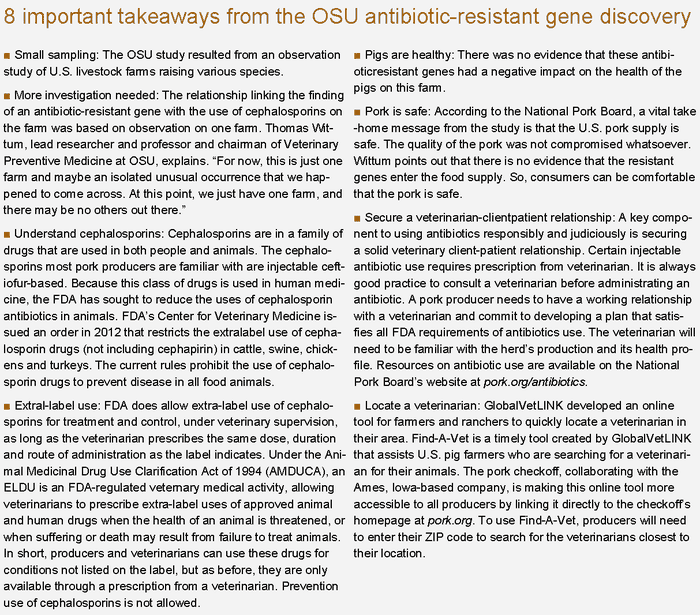

After testing numerous samples for many years, a team of researchers from the Ohio State University found an antibiotic-resistant gene on one hog farm in the United States. The lead researcher, Thomas Wittum, professor and chairman of Veterinary Preventive Medicine, tells National Hog Farmer the goal of this observant study, funded by the USDA National Institute of Food and Agriculture Competitive Grants Program, was to scour U.S. livestock farms, looking for carbapenem- resistant enterobactericeae — drug-resistant bacteria.

The scope of the surveillance was not limited to Ohio or hog farms, but was designed to survey across America’s livestock farms with different species, veterinarian facilities and other health care environments. All the farms volunteered to participate in the study, and the research team fully disclosed the details of the project.

Still, antibiotic resistance has never been recovered from U.S. livestock farms participating in the observation study until now. “We put this surveillance in place and took samples in various ways from various sources. We screened a lot of samples over several years without finding any evidence that these were present,” explains Wittum. “Then we happened to come across this single farm where we found a carbapenem-resistant organism. As we did additional sampling, we found it widespread in one barn on this farm.”

The researchers initially discovered the antibiotic-resistant gene in the nursery barn on a 1,500-head, farrow-to-finish farm. In pursuit of searching for additional CRE, several species of bacteria with the same resistance gene, known as IMP-27, were identified in the farrowing barns, but not in the finishing unit. Wittum notes that CRE was rarely found in the nursery, but quickly discovered in the farrowing facility.

The combing of the hog farm also included testing the fecal matter of all pigs — sows, piglets, growers and finishers. In the first abstract published in Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, the researchers note that CRE was only located in the environment. However, Wittum confirms that since the publishing of that paper, the team has recovered it from both the sows and piglets in that barn as well. He says, “We primarily found it in the environment, but since then we did an additional sampling and know the pigs also can shed these resistant organisms.”

At press time, that data had not been released.

What is the big deal?

The Ohio State research team found the transmissible CRE, a bacterium carrying a rare gene that hinders carbapenems, a class of antibiotics used to fight germs that have already become resistant to other drugs.

Carbapenems are never used in animals intended for food in the United States, explains Dave Pyburn, DVM and National Pork Board senior vice president of science and technology. It is not allowed by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Nevertheless, other types of beta-lactam antibiotics, such as cephalosporins, are sometimes used on farms to treat sick animals under veterinary supervision.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention considered CRE as an “urgent” public health threat because this multidrug-resistant bacteria has been found in hospitalized patients. “These carbapenemresistant organisms are generally found in hospitals, but we’re starting to see some outside of a hospital. So, we want to look on farms and see if we could find them,” explains Wittum.

While finding CRE at a livestock farm is definitely concerning, the resistant gene was found in samples from farrowing and nursery and not in feces of market hogs. The conclusions of the study are drawn based on this one barn result without further validation, replication and research, and demonstrate that this issue requires additional study.

Connecting the dots

While the recently published report documents the dissemination of a carbapenem-resistant gene in the environment of a single swine farrow-to-finish operation in the United States, the researchers also note a relationship between the discovery and ceftiofur use on the farm. According to Wittum, the farm was treating piglets in the farrowing house with the antibiotic ceftiofur. This is in the same barn where the antibiotic-resistant gene was prevalent.

In the two barns — nursery and finishing — that antibiotic was not used, CRE were barely found. Only an isolate was present in the nursery barn, and there was no evidence in the finishing barn. He says, “Clearly, the same barn where they are using cephalosporins is where we find these resistant organisms and that resistant gene. They were located in the same place. So, we hypothesized that use of ceftiofur supported the spread of resistant bacteria and gene in that barn.”

In the results of the published study, the researchers state: “All piglets in the farrowing barn routinely receive a prophylactic ceftiofur treatment at 0-1 day of age, and males receive a second prophylactic ceftiofur treatment when they are castrated at 5-7 days of age. Sows in the farrowing barn receive therapeutic ceftiofur as needed for treatment of metritis and other bacterial infections.”

In accordance with FDA, the use of ceftiofur in a prevention manner is prohibited, says Harry Snelson, DVM and American Association of Swine Veterinarian director of communications. “Ceftiofur is labeled for control or treatment of specific diseases in pigs. It is not labeled for prevention use.”

During the interview, Wittum discloses the farm was treating piglets with ceftiofur to control a specific disease outbreak. He agrees with Snelson that the use of this drug for prevention is not allowed. “They were using it to treat and control a problem. They were definitely using within the label,” Wittum says firmly.

Be that as it may, the researchers state in the published study appearing in the December 2016 issue of the American Society for Microbiology Journal that it is common practice for U.S. hog farmers to use ceftiofur in a preventive matter. Wittum and the other authors write in the abstract, “As is common in U.S. swine production, piglets on this farm receive ceftiofur at birth, with males receiving a second dose at castration (≈day 6). This selection pressure may favor the dissemination of blaIMP-27-bearing Enterobacteriaceae in this farrowing barn.”

This statement that ceftiofur used in preventive manner is common practice for America’s pig farmers is now free for the world to read. A statement far from the truth for numerous reasons, warns Pyburn.

“As a veterinarian, we know the use of cephalosporins for disease prevention is illegal per the FDA. Also, as veterinarians, we took an oath to protect animal and public health. This would go against that,” says Pyburn. “Thirdly, this stuff is expensive. I do not think it is used in every pig prophylactically because of the expense.”

Furthermore, he explains, the latest sales data for animal pharmaceuticals does not reflect enough ceftiofur sold to be a widely used for prevention on U.S. hog farms. “Look back at the most recent FDA sale statistics from 2014; 0.2% of all sales are ceftiofur. If we are using it very commonly in our pigs in the industry in a preventive way, wouldn’t the sales figure be a lot higher? I think they inappropriately called this common in swine production,” Pyburn notes.

Where did it come from?

Swine health experts and the OSU research team are unclear how this type of resistant gene, commonly found in human health facilities, enter the hog farm. Wittum openly admits, “We really believe it was introduced to the pig farm from an outside source. We do not know where it came from. Our best guess, for us, is a gene that emerged from a hospital somewhere and somehow, probably with people, moved from that to the pig farm and introduced into the pigs in that way. It spread around in the pigs based on the antibiotic use on the pig farm.”

Still, it is a large leap to draw a conclusion based on an observation made on one farm. The researchers construe the spread of the carbapenem- resistant organisms throughout the farrowing barn is boosted by the use of ceftiofur in the farrowing barn. Basically, Pyburn says, “the researcher took this to mean it must be the ceftiofur at the farrowing barn level that it is selecting for this resistant gene to be present.”

Pork is safe

It is important to note that the antibiotic-resistant bacteria were not found beyond the farrowing and nursery facilities. So, the finishing barn and the market hogs were free from the carbapenem-resistant organisms. Wittum stresses, “It seems to be contained. It is pretty clear the animals are not carrying with them through to the finishing barn where it can go into the food supply. There is no evidence whatsoever that these are going into the food supply.”

The resistant gene identified in the study was not found in a market hog, and there was no threat to food safety. Pyburn says, “Food is safe. We are not sending pigs from this farm to slaughter carrying this gene.”

Snelson says, “It is an interesting finding. The study was confined to the one farm, but the findings are pretty limited. At this point, I would not put too much emphasis on it. It warrants additional research to try to narrow some of those things down to determine if there are practices occurring on the farm that contribute to the development of resistance, and how we might address those going forward.”

While additional investigations are needed and many questions remain unanswered from the OSU research, Snelson says there are lessons to be learned.

For hog farmers, Snelson says, “There are requirements associated with how these products can be used on the farm. They need to follow label directions and follow the directions of the veterinarians. They need to understand that veterinarians have legal requirements they must follow on how these products are used.”

You May Also Like