Sickness eats into pigs’ energy consumption

Health challenges impair pigs' production efficiency and profitability.

April 27, 2017

By Nichole Huntley, Ph.D. candidate, and John Patience, Professor, Iowa State University; and Martin Nyachoti, Professor, University of Manitoba

Winter months filled with cold weather, the common cold and risk of contracting the flu are thankfully behind us for the year, but we can all easily think of what it feels like to be under the weather. Chills, lack of appetite and fatigue are symptoms we associate with infection, and pigs experience similar symptoms when facing health challenges. These symptoms arise from underlying physiological changes aimed at preparing the immune system to best defeat the pathogen challenger.

Sick pigs do not perform well; feed intake drops, growth slows and consequently days required to reach market weight increases. While symptoms of infection are well understood, interactions between the immune response and nutrient metabolism are continuing to be uncovered.

To ensure health and vitality of the body, the immune system has high biological priority. Thus, when pathogens are detected, the immune response becomes the body’s energetic priority and changes how dietary nutrients and energy are utilized. Therefore, a perceived immune challenge can theoretically partition energy and nutrients away from productive processes such as muscle growth, and negatively impact the efficiency and cost of meat production.

Research continues to emerge on the nutrient requirements of the activated immune system. Work by Nick Gabler and Lance Baumgard’s research groups at Iowa State University has examined shifts in amino acid requirements and identified significant increases in glucose requirements in the face of a health challenge. Our research group was interested in answering the question “how does an immune response impact pigs’ maintenance energy needs?” Our recent research reveals that it is more than just the drop in feed intake slowing growth during an immune challenge.

We conducted an intensive study with 30 nursery pigs to determine the energetic cost of immune stimulation using lipopolysaccharide. LPS contains E. coli cell fragments that “trick” the immune system into thinking bacteria are present, and stimulates the front-line innate immune system to respond to an infection. In this study, four LPS injections induced fever and incited a systemic inflammatory response. We measured its effects on nutrient digestibility, nitrogen balance and maintenance energy requirements to help us understand the larger picture of how the immune response influenced energy use in the pig.

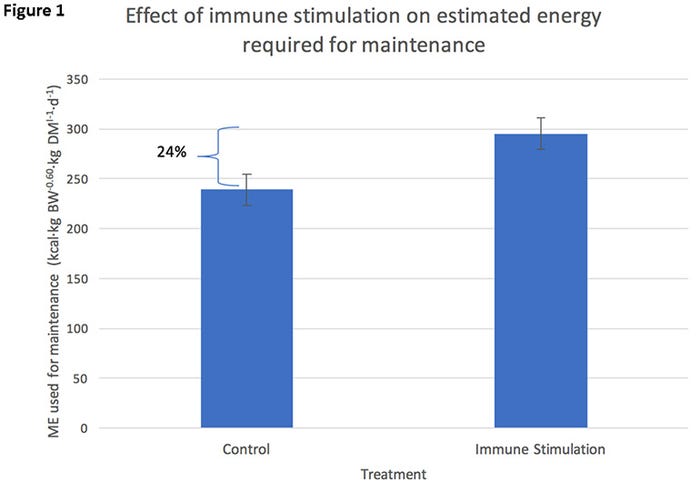

We found that health-challenged pigs utilized 24% more energy for activation and maintenance of an innate immune response (Figure 1). Pigs in this study were limit-fed, so the repartitioning of energy toward the immune system limited energy available for fat deposition and weight gain. This resulted in a 27% decrease in fat deposition and 26% decrease in average daily gain.

It’s important to remember that in this experiment the pigs, by design, ate the same amount of feed. However, in a typical situation when pigs get sick, they also eat less feed, which compounds the problem of less energy being available for growth. As we start thinking about possible nutritional interventions to support optimal growth performance and feed efficiency during a health challenge, feeding a more energy-dense diet could be a potential strategy. Considering the intricate interaction among amino acids and energy, our finding that an immune response substantially shifts energy away from muscle growth suggests it is likely that a mismatch is occurring between the dietary amino acids no longer being utilized for growth and the requirements for immune cell production and function. Aptly, this is a topic receiving considerable research attention in swine nutrition and immunology.

The results of our research demonstrate the substantial energetic cost of infection and support the knowledge that there is great economic importance in maintaining a healthy population. Any energy that is partitioned to fight disease is not available for growth. Thus, health challenges impair production efficiency and profitability. Incorporating this understanding into your production nutrition and economic models and decision-making may help prioritize and incentivize maintenance of a high-health herd.

You May Also Like