Selecting and managing gilts for optimal reproductive potential

Identifying gilts best suited to enter breeding herd has significant challenges.

January 5, 2021

Efficient pork production is largely impacted by the reproductive success of the sow farm. Therefore, when it comes to sow lifetime productivity, it is critical to think about gilt development and how to best prepare farms’ largest parity population for future success. Given the high impact that environment and management can have on longevity and the low heritability of fertility and associated traits, identifying gilts best suited to enter the breeding herd has significant challenges.

Factors important to gilt development—growth rate, activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis and early ovarian development—can be highly variable within a gilt pool. Moreover, these traits may either be not easily measured or not practical to measure on commercial farms. As such, age at puberty is the most predictive tool available to producers for identifying a gilt’s reproductive potential. Gilts that reach puberty at a younger age are more likely to reach first, second, and third parity (Serenius and Stalder, 2006; Wijesena et al., 2017), and are also associated with improved retention rate and longevity in the sow herd (Patterson et al., 2010).

However, solely using age at first estrus to quantify reproductive potential has limitations, especially given gilts on today’s sow farms may not be introduced to mature boars early enough to identify those with early reproductive maturity. Additionally, if a gilt reaches 30-plus weeks of age with no documented estrus, the producer must either keep investing resources into a gilt who is likely not reproductively sound or cull her and suffer the losses of purchased price and/or feed and housing costs.

Several weeks prior to the producer ever detecting estrus behavior, however, the reproductive tract begins to undergo maturation. During a gilt’s growing phase, the reproductive tract becomes responsive to neural changes in the hypothalamus and pituitary resulting in early follicular development. As a result, this increase in follicle development produces estrogen and increases in total reproductive tract size as early as 70 days of age (Dyck and Swierstra, 1983). Furthermore, Flowers et al. (2014), determined that a prepubertal gilt with increased vulva reddening and swelling in response to low levels of gonadotropins had a greater likelihood to reach later parities, indicating that those exhibiting earlier receptivity to circulating hormones may be more desirable as replacements.

With a correlation between age at puberty to breeding herd stayability, and the potential link to early reproductive tract development, a series of studies were conducted at Iowa State University to look at developmental changes in vulva size as a potential biomarker for reproductive related traits. Graves et al. (2020), investigated the developmental time point when the widest variation in ovarian development exists and determined whether a relationship exists between the age of prepubertal ovarian development and the age at onset of puberty.

One hundred fifty-five gilts were originally designated to the study, where beginning at 75 days of age vulva length and width measurements were taken and repeated every ten days after for four additional time points (days 85, 95, 105, 115). Ten gilts were sacrificed at each time point to measure ovarian development and uterine weight changes. The remaining 105 gilts remained in production and were exposed to boars daily beginning at 129 days of age and ending at 200 days of age to determine association between prepubertal vulva characteristics and age at first estrus.

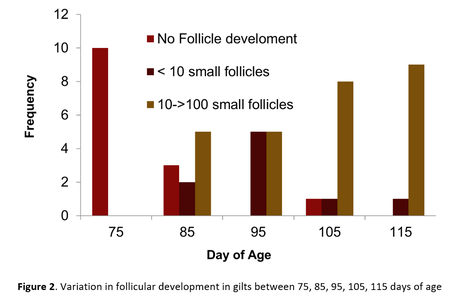

When follicular development was assessed, notable differences were found between gilts (Figure 1), as well as dramatic changes over the different time points. At day 75, no gilts exhibited any follicular development, however, by day 115, all gilts displayed at least some level of ovarian development (Figure 2).

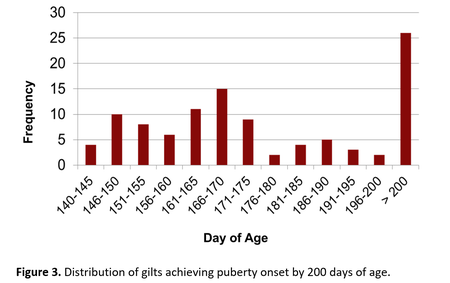

Puberty onset was recorded at the age when first behavioral estrus was observed for each gilt. Seventy-nine out of 105 gilts demonstrated estrus before 200 days of age, with the earliest showing estrus by day 140 and an average age at first estrus of 165 days of age (Figure 3).

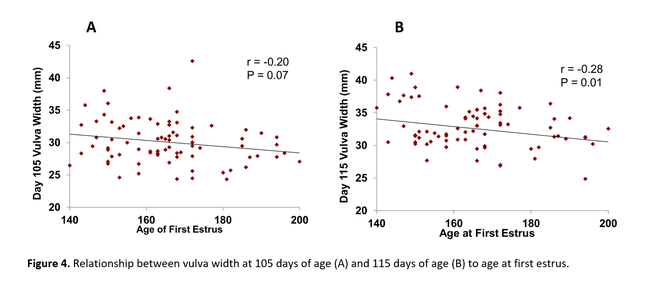

Twenty-six gilts were classified as not displaying estrus by 200 days of age withing the time frame monitored. Interestingly, of the gilts that reached puberty there was a tendency (P = 0.07) for correlation between vulva width at 105 days of age and age at first estrus (Figure 4a), and was significant (P = 0.01) when 115 day vulva width was compared to age at first estrus (Figure 4b).

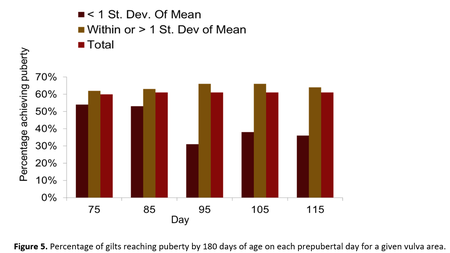

To determine the practicality of selecting gilts based on prepubertal vulva characteristics, gilts were grouped based on vulva area (vulva length x vulva width) into either below average (< 1 St. Dev. of Mean) or average/above average (Within or > 1 St. Dev. of Mean) for each day that vulva measurements were recorded (day 75, 85, 95, 105, 115). When analyzing the percentage of gilts achieving estrus by 180 days of age, vulva area measurements on day 75 and day 85 were less predictive when comparing gilts below average for vulva area and those average or above for vulva area (Day 75, 54% vs. 62%; Day 85, 53% vs. 63%). For days 95, 105 and 115, gilts classified average or above for vulva area had notable increases in their ability to reach puberty by 180 days of age compared to those classified below average (Day 95, 31% vs 66%; Day 105, 38% vs. 66%; Day 115, 36% vs. 64%) (Figure 5).

With the high degree of variation in puberty onset in commercial gilt pools, and the labor required to properly develop gilts, identifying those with the greatest reproductive potential was challenging. The physiological development of the vulva may be a valuable selective tool for identifying replacement gilts that have a higher chance of entering the commercial breeding herd and becoming more productive as evidenced by reducing the number of nonproductive days and increasing sow productive lifetime averages among the breeding herd female population.

Key takeaways

Gilt reproductive tract development begins prior to 100 days of age and is variable within gilt population.

As vulva width at 115 days of age increased, age at first estrus decreased.

Gilts within or above 1 standard deviation for vulva area at days 95, 105, and 115 were 20-30% more likely to reach puberty by 180 days of age, compared to gilts below 1 standard deviation for vulva area.

Application- Vulva size showed to have potential value as a marker for gilts regarding reproductive maturity and puberty attainment.

Published Work: Graves et al., Translational Animal Science, Volume 4, Issue 1, January 2020, Pages 285–292

Sources: Matthew Romoser and Jason Ross, who are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

References

Dyck, G. W., and E. E. Swierstra. 1983. Growth of the reproductive tract of the gilt from birth to puberty. Can. J. Anim. Sci. 63(1):81-87.

Patterson, J. L., E. Beltranena, and G. R. Foxcroft. 2010. The effect of gilt age at first estrus and breeding on third estrus on sow body weight changes and long-term reproductive performance. J. Anim. Sci. 88(7):2500-2513.

Serenius, T., And K. J. Stalder. 2006. Selection For Sow Longevity. Journal Of Animal Science 84 Suppl:E166-171. (; Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't; Research Support, U.S. Gov't, Non-P.H.S.; Review)

Wijesena, H.R.; Lents, C.A.; Riethoven, J.J.; Trenhaile-Grannemann, M.D.; Thorson, J.F.; Keel, B.N.; Miller, P.S.; Spangler, M.L.; Kachman, S.D.; Ciobanu, D.C. Genomics Symposium: Using genomic approaches to uncover sources of variation in age at puberty and reproductive longevity in sows. J. Anim. Sci. 2017, 95, 4196–4205

You May Also Like