Relationship between sow culling types and parity trends

Findings from a recent study showcase the vulnerability of various sow parities in relation to culling types in swine herds of Midwest U.S.

November 27, 2019

Reasons for sow culling in piglet producing commercial sow herds have been well documented, and various studies have found out that major reasons are associated with reproductive problems and lameness, as well as low levels of productivity (Lucia et al., 2000; Segura-Correa et al.,2011). The decision to replace sows depends mostly on average herd productivity.

Different characteristics of sows, such as productivity, age at first farrowing, and stage within productive life, as well as living conditions and management practices within the farms, impact longevity. On commercial farms in the United States, annual culling rates often exceed 50% and many sows are replaced before their third or fourth parity, corresponding to potentially the most productive period in the life of a sow (Hoge and Bates, 2011).

Sow removal continues to receive more attention due to its economic and ethical importance since a high removal rate is associated with poor longevity. The aim of this article was to illustrate removal types in commercial swine herds by characterization and quantification to give an insight on how various parities are eliminated from the farm herds.

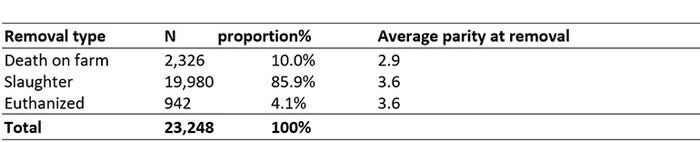

A total of 23,248 culled sows for a period of four years (2015-18) was examined for sows culled from commercial breed-wean sow herds in Midwest United States. Three removal types were identified as the main ways through which gilts and sows are eliminated from the herds, where by slaughter was the most common removal type followed by death on farm and euthanized sows (Table 1).

Death on farm included all the sows that died due to known/unknown disease. Death on farm in swine operations negatively impacts sow longevity and has economic implications. As seen in this study, most sows that succumb to death are younger sows with less than three parities in performance, posing an economic crisis. A sow remaining in the breeding herd for fewer parities is likely to produce fewer pigs in her lifetime, compared to a sow that remains in the breeding herd for a longer period of time. Disease as a contributing factor to sow mortality could have major revenue losses as in the case of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome which has been recorded to have an annual total cost of $663 million per year in U.S. swine production (Holtkamp et al., 2013).

Slaughter constituted almost 86% of the total sows culled due to common reasons such as old age, farrowing productivity and reproductive failure. Increase in chronological sow age is directly proportional to an increase in parity age, hence sows removed due to old age also have a high chance of being removed due to low farrowing productivity/lactation to weaning productivity indicating decreased performance with increase in age. Sows sent to slaughter also have significant problems related to reproductive failure that could account for more than 30% of the sows removed in herds (Mote et al., 2009)

Euthanasia is the humane process whereby the sow is rendered insensible, with minimal pain and distress, until death. Ideal euthanasia process should be quick, effective and reliable. In this study, 4.1% of the sows were eliminated from the herd by euthanasia implying that most of those sows could have been:

Sows that show inadequate health improvement or minimal prospect for improvement after a certain number of days of intensive care.

Severely injured and non-ambulatory sows with the inability to recover

Sows immobilized and with a body condition score of 1.

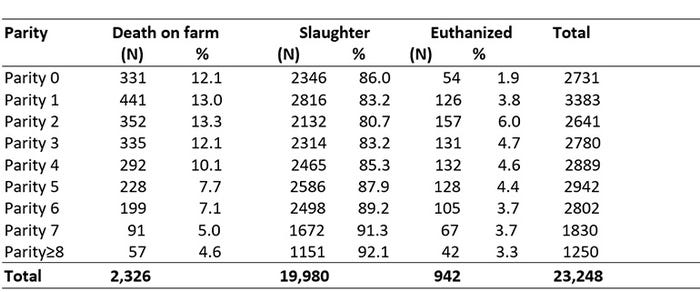

In Table 2, Death on farm slows down as parity increases from Parity 2. Individual sows could take a while to acclimatize in the herd structure by building up a strong progressive immunity after their introduction as breeding gilts. However, death as a factor of removal in relation to parity could be undetermined in the case of a severe disease impact like porcine epidemic diarrhea which ravaged most swine farms in the United States during the 2013-14 outbreak.

Slaughtered sows increase from Parity 2 due to the fact that since many removals by slaughter are attributed to farrowing productivity and reproductive failure. The strictness of efficiency of production and the need to reduce non-productive days in U.S. swine production leads to most sows getting no second chance to stay in herds. Furthermore, Tummaruk et al., (2001) established that parity total born starts to decline as from Parity 4 posing a significant likelihood of Parity 4 or higher sows getting culled due to farrowing productivity. As sows grow older the vitality and purity of the reproductive tract slows down from the past experiences of pregnancies making them vulnerable for removal by slaughter since they don’t maintain the productive numbers that are often sought in commercial piglet producing herds.

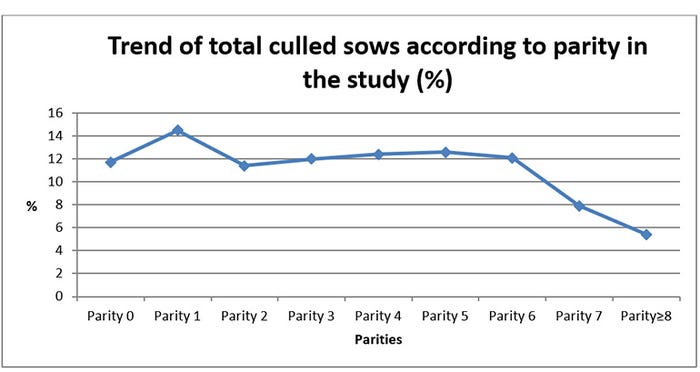

Overall as seen in Figure 1, culling was highest in younger parities as compared to older parities. Removal of younger parities from the herds affects the herd age structure and prevents most of the sows from reaching peak performance. Estimations from Scholman and Dijkhuizen, (1989) indicate that the optimal economic lifespan being at least five parities that can produce a viable net return. Understanding the trend of sow removals in the herds provides valuable information for which swine producers and veterinarians can directly use for planning purposes and production scheduling to increase productivity in the swine industry.

References

Hoge, M.D., and Bates, R.O., (2011). Developmental factors that influence sow longevity. Journal of Animal Science. 89, 1238-1245.

Holtkamp, D.J., Kliebenstein, J.B., Neumann, E.J., Zimmerman, J.J., Rotto. H.F., Yoder, T.K., Wang, C., Yeske, P.E., Mowrer, C.L., and Haley, C.A (2013). Assessment of the economic impact of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus on United States pork producers. Journal of Swine Health Production .21,72-84

Lucia, T., Jr., Dial, G.D., Marsh, W.E., (2000): Lifetime reproductive performance in female pigs having distinct reasons for removal. Livestock Production Science. 63, 213-222

Mote, B.E., Mabry, J.W., Stalder, K.J., and Rothschild, M.F., (2009). Evaluation of current reasons for removal of sows from commercial farms. The Professional Animal Scientist. 25, 1-7

Scholman, G.J., and Dijkhuizen, A.A., (1989). Determination and analysis of the economic optimum culling strategy in swine breeding herds in Western Europe and the USA. Netherlands Journal of Agricultural Science 37, 71-74.

Segura-Correa, J.C., Ek-Mex, E., Alzina-López, A., and Segura-Correa, V.M., (2011). Frequency of removal reasons of sows in Southeastern Mexico. Tropical Animal Health and Production. 43, 1583-1588

Tummaruk, P., Lundeheim, N., Einarsson, S., Dalin, A.M. (2001): Effect of birth litter size, birth parity number, growth rate, backfat thickness and age at first mating of gilts on their reproductive performance as sows. Animal Reproduction Science. 66:225-237

Source: Joab Malanda, who is solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly owns the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like