PRRS incidence continues to perplex producers

Research on PRRS seasonality analyzed the temporal patterns of PRRS infections at the farm level for Minnesota, Iowa, North Carolina, Nebraska and Illinois.

November 14, 2017

North American hog producers know a lot about porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. They know that PRRS is still the costliest pathogen to hit swine herds, costing U.S. producers $580.62 million in 2016. Producers also know they can do their best to keep it out of their herds, but it can still find its way in. Producers also understand that they can set their calendar to when PRRS will strike — Oct. 15 is the magic date that the virus begins to inflict its wrath on U.S. swine herds.

Or is that the case?

Andréia Arruda, an assistant professor in the Ohio State University Department of Veterinary Preventive Medicine, was involved in a research project to more closely study the seasonality of this deadly hog disease, and her findings shed new light on the certainty or uncertainty of PRRS infections.

Arruda presented research findings at this year’s Allen D. Leman Swine Conference as she dug deeper into data was already available through the Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project. Arruda, originally from Brazil, graduated as a veterinarian from São Paulo State University in 2010, before coming to the University of Minnesota to get her master’s degree and then her doctorate from the University of Guelph. While she was at the University of Minnesota, she and the late-Bob Morrison worked on a PRRS seasonality project using data collected through the MSHMP, which now bears Morrison’s name.

Arruda says deeper study into the MSHMP data paints a picture that’s more blurry when looking at or attempting to predict PRRS’s seasonality.

“We learned early the lesson that mid-October to February is PRRS’s seasonal pattern,” she says, by looking at the surface of the MSHMP data, which is voluntarily exchanged by producers and veterinarians to obtain a clearer picture of the nation’s herd health status. “We have developed that predictability to be on the lookout that the PRRS season is coming. Previous studies had shown that weekly incidence of PRRS was low during spring and summer, and high during fall and winter.”

However, Arruda points out that researchers from an earlier research project looking at the temporal and spatial dynamics of PRRS infection in the United States caution that some U.S. swine production areas, such as hog-dense regions of Oklahoma and North Carolina, were underrepresented in the spatial statistics. “Thus, the results of that project may not accurately reflect the PRRS impact in those areas,” she says.

Last year when she was working with the MSHMP, she took a closer look at the data from the PRRS breaks going back to 2009, and saw substantial summer breaks across the United States. Arruda then wanted to try to estimate a parameter called the “time-dependent reproductive number” (TD-R) for PRRS, which is well-known in the “modeling world” to calculate the number of new infections that one case could potentially cause. TD-R can tell researchers about the transmissibility of a pathogen in different populations over time, as well as allow for the recognition of “super spread” events; you can also test the efficacy of interventions. TD-R is the measurement to help researchers determine how endemic a disease is, “and we know PRRS is endemic, so it tends to have a TD-R of 1. If it’s over 1, then it’s spreading. If it’s less than 1, it’s dying out,” she says.

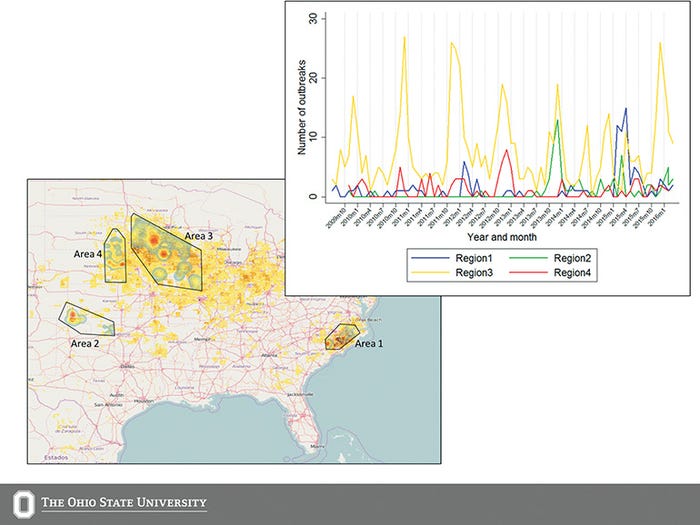

To get a better idea of PRRS spread and estimate this TD-R number, Arruda and her team divided the hog production areas of the United States into individual regions. Again relying on the data from the MSHMP, they saw that the patterns of disease transmissibility varied considerably across U.S. regions.

The objective of Arruda’s research on PRRS seasonality was then to analyze the temporal patterns of PRRS infections at the farm level for five major swine-production states across the United States — Minnesota, Iowa, North Carolina, Nebraska and Illinois. “In other words, we wanted to ask the question, Are yearly patterns commonly described for PRRS conserved across different U.S. states?” she says.

Andréia Arruda and other researchers looked at the incidences of porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome in four hog production areas of the United States using data from the Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project. By mapping the frequency and seasonality of PRRS incidences, researchers get a better picture of the variations of the virus spread.

Digging through weekly data from the lifespan of the MSHMP, 2009-16, Arruda’s team was able to obtain a good picture of PRRS by using an autoregressive integrated moving average model to look for trends and test for different seasonalities. “So we were asking the model, Do we see something that covariates every six months, every four months, every three months or yearly?” she says.

Using the example of Iowa PRRS breaks since 2009, Arruda says it shows the typical pattern of peak breaks as one would expect for when PRRS hits the Midwest state. “But then we decompose this time series and look at the data even further; we are also able to recognize, for example, a constant linear increase in PRRS breaks for this specific state.”

To get the best picture for their research, data were used from all systems for which “we had complete data, so that was over seven years’ worth of data that we had from 302 farms in 13 different systems from the five different states,” Arruda says.

Finally, results from the final models showed a remarkable difference in PRRS seasonality among the states. Three states — Minnesota, Nebraska and North Carolina — showed the typically described annual peaks, while Iowa PRRS breaks peaked every six months and Illinois experienced no particular PRRS seasonality. “More interestingly for me, Minnesota and North Carolina appeared to have the exact same seasonality features, which means there is something very similar in those two regions, even though they are geographically quite far apart.”

As for Illinois’ lack of seasonality, “I don’t want to say that the breaks are random, but we cannot predict how far apart those breaks are happening,” she says.

Some potential hypothesis can be drawn for differences and similarities seen across regions. Arruda points to landscape and environmental factors that may lead to the variations in PRRS peaks by region, as well as the movement of hogs into and out of systems within these regions.

“We also cannot rule out how people are identifying the outbreaks because the way this system is set up, we rely on the veterinarian’s judgement, and we know some areas may have more farms that are vaccinated than others, which can play a role on diagnosis of new breaks — so that’s something to keep in mind,” Arruda acknowledges.

Summer breaks in Iowa may be explained by commingling opportunities, Arruda says, “so maybe there’s just an increase in the opportunity to bring something back to the farm.” Another possible cause of summer breaks may be due to the common perception “that since we think of PRRS as a winter disease, we could potentially be relaxing our biosecurity” the rest of the year.

The simple dynamics of the swine industry, how big it is, and all of the activities surrounding a hog operation — including all the service providers in addition to normal farm activity — tend to assist in the spread of the disease.

Research limits

As an epidemiologist, Arruda is prone to look at the limitations of research. Some limitations she points out are that only sow herds were evaluated; if grow-finish farms were included, the data picture may be painted quite differently. Also, as mentioned, only five states were assessed, “and I would like to have been able to study other states that are very important in terms of pork production,” she says.

Since the MSHMP is a voluntary program, not all production companies are represented. There are about 29 companies that voluntarily provide herd health information to the MSHMP, representing about 50% of the nation’s sow herd.

Arruda sees potential future applications of her research that swine health professionals could predict by region to see if this model holds true for the future. As more producers in more states get on board with disease reporting, the model will only be strengthened by the herd health picture that will be painted.

She also acknowledged that incidence of specific strains of PRRS was not tracked, but that it would be possible to go back to available MSHMP data to see if various strains occur at different times of the year.

Seasonality or not, producers and veterinarians are all on board to prevent PRRS breaks, and Arruda shared recent research showing that highly inclined terrain, and the presence of shrubs and trees, were associated with fewer breaks in U.S. sow farms. The release of that research brought many questions: How many trees? What kind of trees? Does orientation matter? Does wind direction matter? Does the neighboring farm matter? “I said, ‘I don’t know, I have no idea. Let’s do another study.’ ”

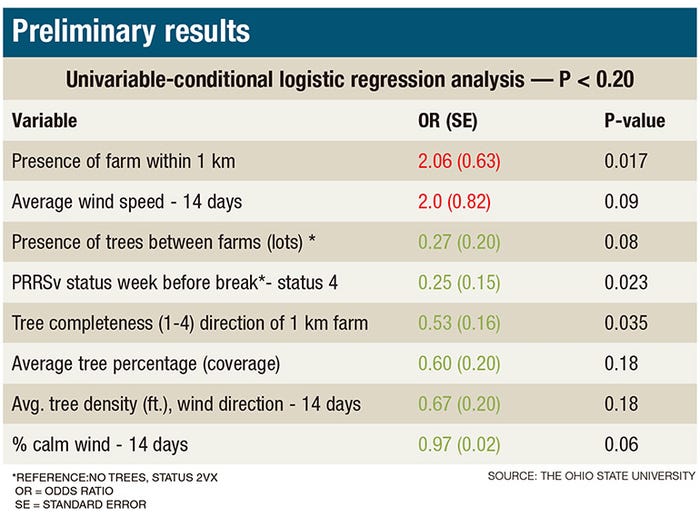

Going into this study, Arruda says the hypothesis was, “Swine farms are more likely to have PRRS outbreaks if the prevailing wind direction from the week preceding the outbreak is directed to areas with no tree coverage.”

Again, using the wealth of data from the MSHMP, Arruda and other researchers took a more detailed assessment of each farm. Cases selected were farms that had PRRS breaks during the MSHMP data period of 2009-16, while the controls were sites that did not have a PRRS break during the same week as the case farm over the same period. Farms were randomly chosen from the eligible farms — 104 cases, 104 controls.

Arruda says producers offered variables that they were interested in, so the research team looked at such things as barn orientation (north-south, east-west or mixed); distance to the main road, and if that road is a highway; presence of farms within 1 to 3 kilometers, regardless if they were hog farms or not; and more in-depth data on tree coverage and weather data.

To study tree coverage, researchers looked at tree density”: “completeness” regarding existing gaps and “percentage” in terms of how much tree coverage exists. Emily Geary, the coordinator of the MSHMP, used Google Earth to locate the farms to aid in the tree assessments. Publicly available weather data were researched by a summer student whom Arruda hired to find the weather data for each particular farm using the closest weather station.

Data collected were the predominant wind direction, percent calm wind and average wind speed for seven and 14 days before the PRRS break was recorded. Results are only preliminary at this point, but Arruda found two factors jumped out as risk factors for PRRS — presence of a farm within 1 kilometer and average wind speed. “So the higher the average wind speed during the past 14 days before the outbreak was, the higher the odds of the farm to be a case,” she says.

Though research results are preliminary, Arruda says the presence of another farm within 1 kilometer and a specific average wind speed 14 days prior to a PRRS break were factors of higher risk.

Take-home messages

Arruda says producers should not seek solace in the calendar. “Do not assume that there is a high risk for PRRS infection solely in the winter, as our research supports the fact that that is highly region-dependent.” Disease prevention is key to all hog producers’ success, and Arruda says strict adherence to a biosecurity plan is imperative throughout the entire year.

Based on the latest research into the impact of tree and windbreak placements as a deterrent to viral spread, Arruda suggests to producers, “If you have the option, leave trees around your farm, or plant more.”

You May Also Like