PEDV Immunity: Past and Present 9833

How long does immunity last?

September 2, 2014

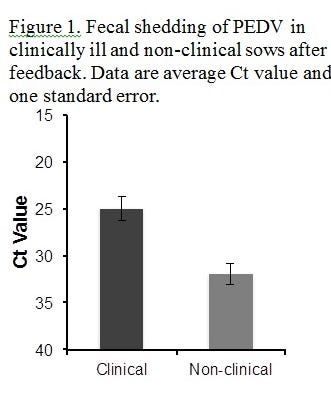

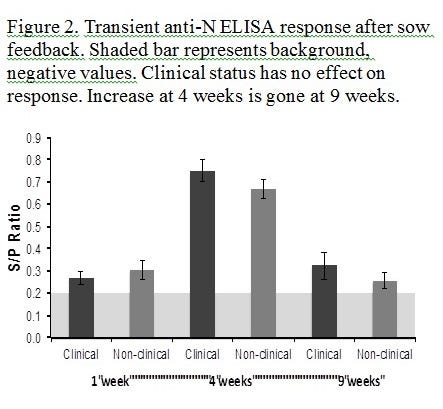

Getting a handle on immunity to porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV) has been difficult. First, it was the absence of antigen reagents to measure serological responses. Then it was trying to figure out if sows really had to show clinical sickness to develop immunity, and if the serological response after feedback really did disappear in a matter of weeks. Working with commercial sow herds in North Carolina, Iowa, and Minnesota, we found that, after one good feedback exposure, sows with or without clinical signs routinely became infected and shed PEDV, but amount of shedding was less in non-clinical sows (Fig. 1). Sows seroconverted but, surprisingly, serum antibodies to nucleocapsid, the ELISA antigen, declined rapidly and were frequently negative at nine weeks after feedback (Fig. 2). The findings indicate that striving for clinical signs in a feedback program is not necessary for immunity, and may put more PEDV into the environment unnecessarily.

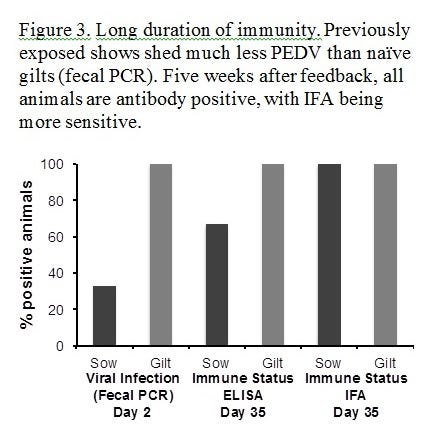

Was immunity really so short-lived? The short answer is no. Working again with a commercial North Carolina producer, we looked at the feedback response of newly introduced, naïve gilts and previously exposed sows in a herd that had a PEDV outbreak and whole-herd feedback four months (134 days) earlier. Two days after the feedback challenge test, all gilts showed clinical signs and shed virus in feces, with 90% showing Ct values less than 30. By contrast, no previously exposed sows showed clinical signs, 50% never shed virus, and the Ct values of shedders were exhibiting Ct values >30 (day 2 shedding is shown in Fig. 3). In conclusion, previously exposed sows were resistant to disease after re-exposure, and the duration of solid immunity was at least four months.

What about serology? On the day of re-challenge by feedback, 40% of previously exposed sows were ELISA-positive (S/P ratio >0.2) to nucleocapsid. Five weeks (35 days) later, all naïve gilts had seroconverted, and 75% of sows were positive. ELISA-negative sows had anti-PEDV antibodies, though, since all sows and all gilts, were IFA-positive (Fig. 3). The lessons learned were that (1) one good exposure to PEDV induces immunity in sows, (2) previously exposed sows are resistant to diarrheal disease months later, but get a boost in immunity, (3) duration of immunity is prolonged, with the full duration not yet known, and (4) measuring nucleocapsid antibodies in serum does not give a full picture of immune status.

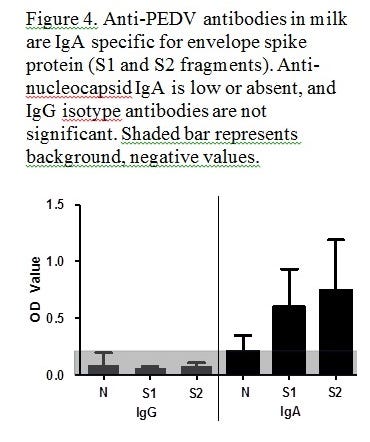

What is the full picture of PEDV immune status? PEDV is an enteric virus. Protection against enteric viruses is due to IgA antibodies secreted into the intestine that neutralize virus and block infection of intestinal epithelial cells. In suckling piglets that have not developed their own immunity, protection is dependent on antibodies in milk. These antibodies also are secretory IgA and ought to neutralize infection by binding to viral envelope proteins. We find that PEDV-immune sow’s milk contains anti-PEDV IgA that is primarily against the spike envelope protein, not nucleocapsid (Fig. 4). We hypothesize that these antibodies protect piglets. Immune sows are expected to also secrete anti-PEDV antibodies into their intestine. Intestinal IgA in the gut, or in milk IgA consumed by piglets, is excreted in feces. Hence, PEDV-specific IgA in feces should correlate with protection. Surprisingly, we have not been able to detect anti-PEDV IgA in feces. As a result, there remain gaps in the picture of PEDV immunity that we are actively working to fill.

The take-home messages for producers are that simple feedback protocols induce good immunity, protection is durable for months, serology can be improved, and lactogenic immunity appears dependent on anti-spike antibodies.

The research was supported by National Pork Board grants 13-262 and 14-175, and support from Zoetis, Inc.

You May Also Like