Lessons learned from Canada’s National Sow Housing Conversion Project

The NSHCP ends its four-year project in December, and conversion experiences on 12 barns have been documented.

October 31, 2017

By Yolande Seddon, University of Saskatchewan, and Jennifer Brown, Prairie Swine Centre

For producers considering a conversion to group sow gestation systems, the process can seem daunting, and with good reason!

Not only is it a considerable investment, there are a number of key considerations to ensure the new group system will be a success. Ensuring that sow health and well-being is properly managed so that productivity can be maintained or even enhanced is key to long-term success and profitability. New scientific data on how best to manage gestating sows in groups continues to grow, however, there remain questions that science cannot easily answer.

In these situations, the experience gained from implementation in real-world farming situations is invaluable. For this reason, swine researchers in Canada joined together to form the National Sow Housing Conversion Project.

The NSHCP is a four-year project (2014-17) that is funded by the federal government and producer organizations. The project is led by Jennifer Brown at the Prairie Swine Centre in Saskatchewan, with collaboration from researchers at the University of Manitoba, the University of Saskatchewan, the Centre du development du porc du Québec and industry partners. The objective of the NSHCP is to document barn conversions across Canada, to better understand the real challenges faced when converting to group housing. The project documents the experience gained by early adopters, which is shared in a central database. Fact sheets have been developed on specific aspects of converting to groups, and the information is being shared in producer presentations and workshops across the country. Providing producers with a combination of practical examples and scientific analysis will improve understanding of group housing systems and their management and help to reduce costly mistakes that could hamper the transition. By supplying this information, the goal of the NSHCP is to facilitate the successful conversion of Canadian producers to group housing.

Now in its fourth year, the NSHCP is coming to an end in December. At the time of writing a total of 12 barns have been documented. In five barns the complete conversion process has been documented, capturing information on the before and after barn layout and herd size, the decision-making process behind going to groups, and lessons learned during the conversion. The remaining seven sites are barns that had already made the conversion to group housing, and the layout, management challenges and lessons learned have been recorded.

Summary of findings

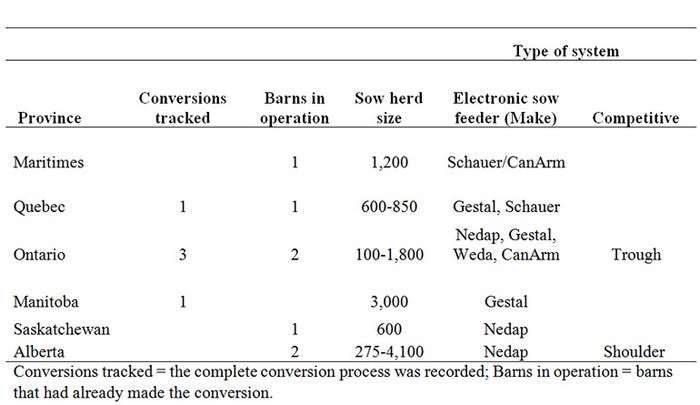

Group gestation systems are typically identified by the feeding system used, because this has a major influence on group management. A wide variety of systems and farm sizes has been documented in order to provide a comprehensive resource to producers. Table 1 shows the herds documented and the type of system used (identified by feeding system). A large majority of farms have chosen electronic sow feeding systems, illustrating that early adopters are keen to make use of new technologies to provide automated individual feeding of sows in a group setting.

Table 1: Sow herds documented for the NSHCP, including herd size, system type and make of electronic sow feeder.

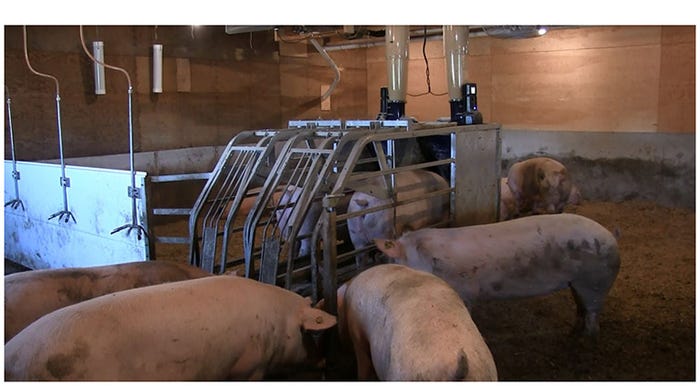

In addition to typical ESF systems which can feed roughly 60 sows per unit, there are examples of the newer free-access ESF systems, which look more like a self-catching feeding stall combined with automated sow detection using radio-frequency identification technology (Figure 1). This system can be used for smaller groups of sows, and is recommended to have no greater than 20 sows per feeder. The ability to individually control feed allowance in ESF systems helps to maintain an even body condition and allows producers to form larger group sizes, and greater flexibility when forming groups as multiple sizes and parities can be grouped together.

Figure 1: A free-access electronic sow feeder (Gestal, Jyga Technologies, QC, Canada). Sows enter the feeder and back up to unclip the gate latch to exit.

Ontario producer John Van Engelen (Figure 2) has installed ESF feeders and implemented a large number of technologies on his farm, including automated sorting and heat detection, a state-of-the art ventilation system, air lift farrowing crates, a pig performance tester and wireless internet. He has presented his innovations at numerous producer meetings, and says that this is the way to interest the next generation of pork producers. As added proof, son, Mitch, and daughter, Cassie, have recently decided to join John in managing their operation.

Figure 2: Gilts in John Van Engelen’s barn rest on the solid lying areas. Note the boar peep hole for heat detection in the background.

Two sites have implemented competitive feeding systems, with one each using trough feeding and shoulder stalls. While competitive feeding systems are much cheaper to install initially, they also require more space due to sows being in small groups. More space must be dedicated to alleys and sows in small groups also require more floor space in order to separate feeding, lying and dunging areas and reduce aggression. As well, more space is needed for comfort or hospital pens for drop outs (room for 10% of sows is recommended).

Competitive systems also require greater observation time and husbandry skills on a day-to-day basis. Sow groups need to be carefully selected and matched for size, otherwise subordinate animals are more likely to be bullied and not have access to feed. On top of these factors, competitive systems require additional feed to ensure that all individuals get a sufficient amount, and a wider variation in body condition is unavoidable. These long-term drawbacks need to be carefully weighed against the initial costs of installation when making the decision to renovate. The two competitive feeding barns documented in the NSHCP are well aware of these drawbacks, and have top-notch managers and staff who work daily to identify problems and treat fall-out sows as needed.

Most common questions being asked

• What type of system to run?

• Grouping of sows: static or dynamic?

• What type of flooring?

• Drinker type (water bowls or nipples) and placement within the pen

• Pen layout and space allowance for lying areas and exercise areas

• Gilt training for ESF

Lessons learned

• Guidelines on space allowance (as outlined in the Canadian Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Pigs) are there for a reason — failure to provide adequate space to sows will result in problems.

• Pen design is very important to promote a calm group of sows.

• Select replacements for leg and foot health, and consider foot trimming in farrowing to treat long toes or dew claws.

• Going to ESF? Be sure to install a good gilt training set up. Also, don’t forget to accustom group-raised gilts to time in stalls (preferably before breeding) to prepare them for farrowing.

Challenges

• RFID tag placement for ESF feeders, lost tags, misread tags

• Lameness is commonly an issue when sows are first moved to groups

For more information on the NSHCP, and to view the barn conversions and available factsheets, visit GroupSowHousing.com. For any questions, contact Jennifer Brown, Prairie Swine Centre, or subscribe to the NSHCP newsletter by contacting Doug Richards, project coordinator.

You May Also Like