Influenza: Dynamic In Pigs and People

During the 1918 human influenza pandemic, clinical signs of respiratory disease were reported in pigs in Europe and in the United States. Since that time, there has been a complex interplay of viruses between humans, poultry (birds) and pigs.

September 15, 2012

During the 1918 human influenza pandemic, clinical signs of respiratory disease were reported in pigs in Europe and in the United States. Since that time, there has been a complex interplay of viruses between humans, poultry (birds) and pigs.

Acute respiratory disease can occur in pigs, but in many instances the infections are subclinical.

Pigs appear to play a role in the reassortment of flu viruses, and this process has been documented repeatedly in the last 20 years.

The 2009 human influenza pandemic of H1N1 arose from a reassortment of North American and Eurasian viruses. That same virus was found in pigs in many areas of the world. Infections in pigs appeared to be initially due to transmission from humans — but then pig-to-pig spread occurred.

The recent occurrence of H3N2 influenza in people attending livestock fairs in a number of states underscores the importance of paying attention to this virus. The H3N2 virus is not uncommon in both pigs and people, and pigs are known to exchange certain strains of the virus. The current H3N2 virus cases occurring in people contain the M gene from the 2009 H1N1 human influenza pandemic virus.

Case Study No. 1

A pork producer has ownership in a sow farm and receives pigs about every nine weeks. The pigs go to several different nursery sites before they are commingled to fill finisher buildings. The pigs from one nursery were getting sick shortly after they moved to the finisher sites. The classic barking cough occurred only in the pigs coming from the one nursery site. Other pigs in the building were unaffected.

Laboratory tests verified that influenza virus was involved. Mortality rates increased during these respiratory events. All of the pigs received a commercial flu vaccine while in the nursery sites.

It is suspected that the initial influenza outbreak was triggered by a staff person who had been ill with the flu. Increased awareness regarding the health status of staff personnel and more attention to detail for hand washing, wearing of masks and biosecurity practices have been implemented.

Case Study No. 2

A 2,400-sow, farrow-to-wean facility receives gilts into an on-site gilt isolation facility every 12 weeks. During the isolation period, gilts are exposed to porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) and given vaccinations for swine influenza virus (SIV), Mycoplasma pneumonia, circovirus, leptospira and erysipelas.

Gilts are moved into the breeding area of the farm after they are shown to be PRRS negative by polymerase chain reaction. After breeding, gilts are moved into the gestating area based on breed dates. The sow herd receives routine vaccinations on a scheduled basis.

About mid-pregnancy, gilts would become ill, characterized by mild coughing, thumping, fever, nasal discharge and some abortions. The owners suspected that PRRS virus was still circulating in the herd. Gilts that recovered farrowed smaller litters, farrowed more mummies than sows and did not successfully lactate.

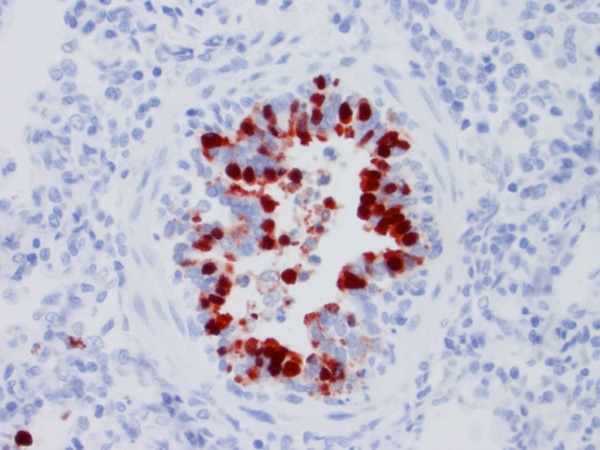

After this occurred in two consecutive gilt groups, more intense diagnostics were done. Gilts and neighboring sows were blood tested to compare PRRS and SIV levels. Nasal swabs were taken from both sows and gilts. Tests were negative for PRRS virus but positive for influenza virus. The virus was not similar to any commercially available antigen.

An autogenous product was created using the virus identified in the affected animals. The whole sow herd was vaccinated with the product, and gilts are now vaccinated during isolation.

It appears the virus in the sow farm was a recombination of several viruses; the adult sows were immune, but incoming gilts were not. Gilt exposure during placement in the gestation area and the common water trough provided contact with infected material. The herd has not experienced clinical influenza disease for nearly 18 months.

Summary

Influenza virus can be fickle and frustrating for a pork producer. The farm’s health advisor needs to do a thorough evaluation of pig flow, biosecurity and personnel health status to determine the probable epidemiology of influenza on a farm. Precise laboratory procedures are necessary to isolate the causative agent. Samples should be collected from pigs having a fever and exhibiting illness. Because the disease has implications for humans, education of owners and farm staff is vitally important.

You May Also Like