Getting piglets over weaning, transport stress

Antibiotic alternative shows promise in commercial conditions.

January 2, 2020

Weaning and transport are stressful times for piglets and can often be the gateway to further health challenges and productivity issues.

In the past, pork producers often included dietary antibiotics to help piglets get through these tense times. However, due to increased consumer concern about the overuse of antibiotics in food-producing animals and recent legislation that prohibits the use of antibiotics in feed without a veterinary feed directive, antibiotics are no longer allowed to be used in this way.

Since the 2017 VFD went into effect, the search has been ongoing for alternatives that can help piglets recover following stressful events.

One alternative that has shown promise is L-glutamine, a conditionally essential amino acid that is a major energy source for rapidly dividing cells, including enterocytes and lymphocytes. Additionally, L-glutamine (GLN) is a key regulator of gene expression and cell signaling pathways.

In a 2017 study, researchers determined that the inclusion of 0.20% GLN in the diets of newly weaned pigs could improve growth rate and well-being more effectively than dietary antibiotics (Johnson and Lay, 2017); however, the study was conducted under controlled conditions using simulated transport and individual housing.

To see if GLN would hold up under real-world environmental conditions, researchers led by the USDA Agricultural Research Service, with support from the National Pork Board, recently conducted a study to see if diets supplemented with GLN could replace traditional dietary antibiotics to improve piglet health and productivity following weaning and transport.

Based on the previous research, it was hypothesized that withholding dietary antibiotics would negatively affect pigs, while diet supplementation with GLN would have similar effects to antibiotics on pig performance and health.

Mimicking market conditions

Piglets of both sexes were weaned around 18.4 days of age and transported for 12 hours in central Indiana. One replicate occurred during the summer 2016; another in spring 2017.

Pigs were sorted by body weight and assigned one of three dietary treatments: A (chlortetracycline [441 ppm] and tiamulin [38.6 ppm]); no antibiotics (NA); or GLN-fed for 14 days. On days 15 to 34, all pigs were provided common antibiotic-free diets in two phases. Therapeutic antibiotic administration was recorded for any health-challenged pigs for the trial duration.

In the nursery phase, diets were corn and soybean meal-based, were fed in four phases and were formulated to meet or exceed nutrient requirements. Pigs were weighed individually, and feeders were weighed every seven days in the nursery period to determine the response criteria of average daily gain, average daily feed intake and gain-to-feed ratio.

On Day 34, all pigs were moved to the grow-finish facility for the remainder of the trial, and pen integrity was maintained.

Common antibiotic-free diets were based on corn and soybean meal, and dried distillers grain with solubles and provided in meal form to meet or exceed nutrient requirements in six phases during the grow-finish period. Pigs and feeders were weighed every 21 days during the grow-finish period to determine the response criteria of ADG, ADFI and G:F.

During the trial, blood samples were collected from one randomly selected pig per pen via jugular venipuncture on days 13 and 33 postweaning and transport.

Piglets were also video-recorded for 14 days immediately following weaning and transport using ceiling-mounted cameras. The video files were later analyzed for behavior observations such as huddling, aggressiveness, eating and drinking.

At the end of the 159-day experiment, pigs from each pen were individually tattooed with their pen number and shipped to a commercial packing facility. Standard carcass criteria of loin and backfat depth, hot carcass weight, fat-free lean index and yield were collected. Fat depth and loin depth were also measured with an optical probe.

Key findings

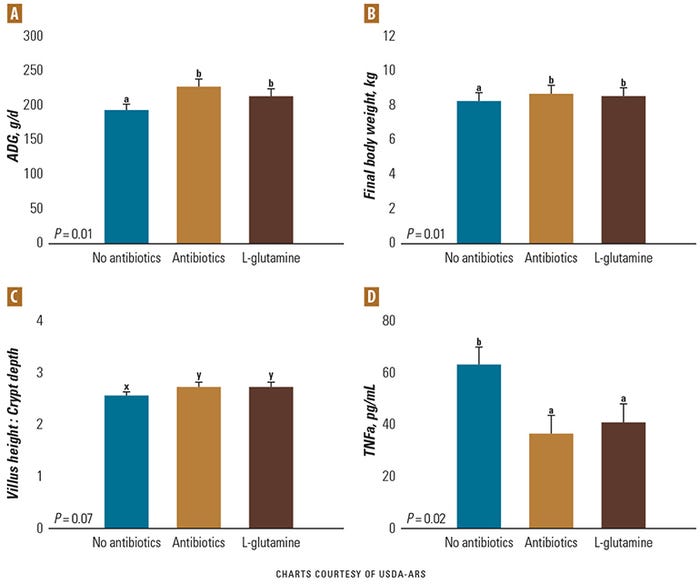

GLN-fed piglets gained weight as well as the antibiotics group. Day 14 body weight and days 0 to 14 average daily gain were greater for treatment A (5.6% and 18.5%, respectively) and GLN pigs (3.8% and 11.4%, respectively) compared with NA pigs, with no differences between A and GLN pigs.

Days 0 to 14 average daily feed intake rose for A compared with NA pigs; however, no differences were found when comparing GLN with A and NA pigs.

Aggressive behavior tended to be reduced overall in GLN compared with A pigs, but no differences were observed between A and GLN vs. NA pigs. However, huddling, active, eating and drinking behaviors increased overall in the spring replicate compared with the summer replicate.

Compared to the NA group, GLN and the treatment A piglets showed lower blood plasma levels of tumor necrosis factor alpha, a biomarker of inflammation.

The meat quality of market-ready pigs from the GLN group was no different than that of the A or NA groups. When hot carcass weight was used as a covariate, loin depth and lean percentage were increased during the spring replicate compared with the summer replicate.

A more feasible option

In conclusion, GLN supplementation improved pig productivity (growth rate) and overall health (improved intestinal development, with no difference in immune function) to a similar extent as feeding treatment A following weaning and transport.

In addition, feeding GLN at 0.2% of the diet cost approximately 18% to 22% less on a basis per ton of feed when compared to dietary antibiotics at the time the study was conducted. Replacing dietary antibiotics with GLN may be a viable option to reduce antibiotic use and producer costs, while simultaneously maintaining pig productivity and appropriate standards of animal welfare.

Researchers: Alan Duttlinger and Kouassi Kpodo, Purdue University and USDA ARS Livestock Behavior Research unit; Donald Lay Jr. and Jay Johnson, USDA ARS Livestock Behavior Research unit; and Brian Richert, Purdue University. For more information, contact Johnson.

You May Also Like