E. coli: Good or Evil?

Cases of both preweaning and postweaning diarrhea can be difficult to diagnose. Several viruses (e.g. rotavirus, transmissible gastroenteritis or TGE), bacteria (E. coli, Clostridium perfringens, Clostridium difficile, Salmonella sp.) and parasites (coccidia) can be involved.

March 4, 2013

Cases of both preweaning and postweaning diarrhea can be difficult to diagnose. Several viruses (e.g. rotavirus, transmissible gastroenteritis or TGE), bacteria (E. coli, Clostridium perfringens, Clostridium difficile, Salmonella sp.) and parasites (coccidia) can be involved. Furthermore, these infectious agents are rarely found alone. It is more common to find combinations of bacteria, viruses and coccidian. Figuring out which one is more relevant can be challenging.

The case of E. coli is especially difficult to interpret because there are numerous, different strains that fall under the “E. coli” species. Some of these strains are good, live in the large intestine of healthy pigs and cause no harm. Others are evil, capable of infecting the small intestine and causing diarrhea.

To determine whether an E. coli isolate obtained from a pig with diarrhea is a pathogenic or a non-pathogenic strain, we rely on several tools to help us figure that out.

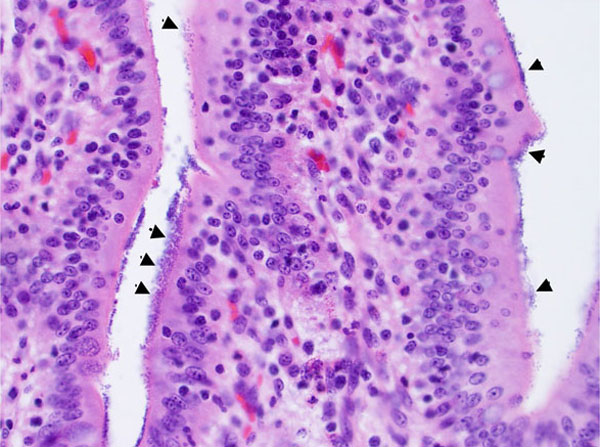

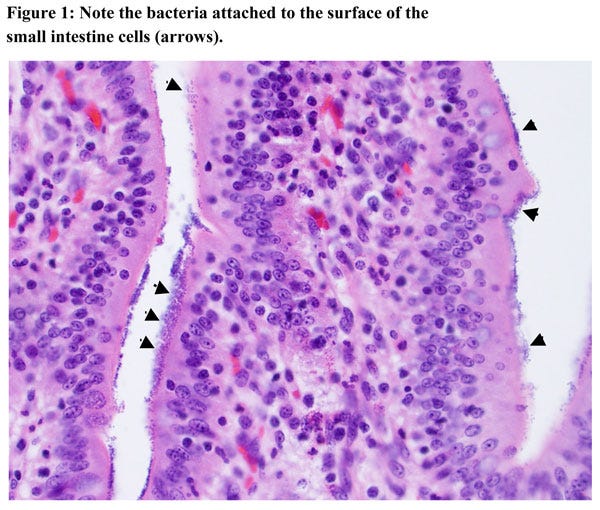

First of all, it is important to work with a diagnostic laboratory that performs a complete workup of diarrhea cases. Such workup should include detection of viruses, bacteria and parasites, as well as microscopic examination of intestinal tissue. This will allow ruling out other potential causes of diarrhea. However, as mentioned before, coinfections are common. In cases where several pathogens are detected, microscopic examination of the tissues will help find out which ones are more relevant. In the case of E. coli infections, the bacteria can be seen attached to the surface of intestinal cells (Figure 1).

Once E. coli is isolated from the intestine of pigs with diarrhea, the next step is to test that particular isolate for the ability to produce virulence factors. Virulence factors are structures or substances that some bacteria can produce and that enable them to cause disease. There are two main types of virulence factors:

1. Fimbriae or pili:These are hair-like structures that cover the surface of the bacterium. E. coli uses its fimbriae to attach to the lining of the small intestine so they do not get flushed away with the flow of intestinal content. There are several types of fimbriae, noted by the letter “F” and a number. The most common fimbriae in E. coli isolated from swine are F4 (also called K88), F5 (also called K99) and F18.

2. Toxins:These are substances that the bacterium produces and cause the secretion of fluids that result in diarrhea. The most important toxins secreted by E. coli isolated from swine are Heat-labile enterotoxin (LT), Heat-stable enterotoxin A (STa) and Heat-stable enterotoxin B (STb).

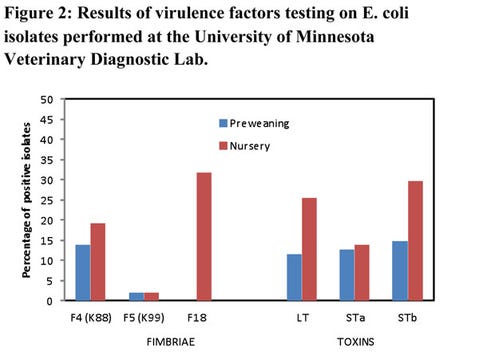

For an E. coli isolate to be pathogenic, it must possess the ability to produce both fimbriae and toxins. At the University of Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, E. coli isolates suspected of being the cause of diarrhea are tested for virulence factors by polymerase chain reaction (PCR). During 2012, 225 isolates were tested. In piglets showing diarrhea in farrowing, F4 (K88) was the fimbriae detected more often, followed by F5 (K99).

In contrast, in weaned pigs F18 was the most common fimbriae (Figure 2). Note, however, that the most common scenario was to find that the E. coli isolate did not have fimbriae at all. Therefore, in those cases, the E. coli isolate was interpreted as non-pathogenic. Of the three main toxins, STb was the one detected most commonly in isolates from both preweaning and weaned pigs (Figure 2).

In summary, virulence factor testing is a very useful tool to figure out if an E. coli isolate is pathogenic or not. For example, an E. coli isolate that tests positive for F4, LT and STb would be interpreted as pathogenic. In contrast, an E. coli isolate that tests negative for all fimbriae and toxins (a very common case) would be interpreted as non-pathogenic.

You May Also Like