Disease management: Time to think like engineer

Moving disease management forward means thinking differently.

December 8, 2016

Big data is all around us. The world of agriculture is embracing cutting-edge technologies at a rapid pace to improve agriculture practices and collect large amounts of data. It is easy to get lost in the cloud computing, new gadgets, algorithms and correlation analysis, foregoing the real mission of optimizing the technology to enhance real pig farming.

Today, tools used for disease management are complicated and highly integrated with lots of moving parts with biological, operational and human behavior variations. However, it is how we incorporate it all together and leverage the big data along with complex models in an appropriate manner that will move disease management forward, says Jim Lowe, D.V.M., Integrated Food Animal Medicine Systems at the College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Illinois.

Speaking at the North American PRRS Conference, Lowe says, “As a veterinarian, I spend a lot of time thinking about how we drive execution at the individual farm and also on a large scale. So, how do you do something 100 times over in a big geographic area to really make an impact?”

Managing persistent diseases, such as porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome, is frustrating for veterinarians and pig farmers. So, better managing a disease that can drain a farm’s profits becomes a priority and the quest to rethink current practices. Optimizing sophisticated models and big data collected for better disease management is about thinking differently, Lowe further explains.

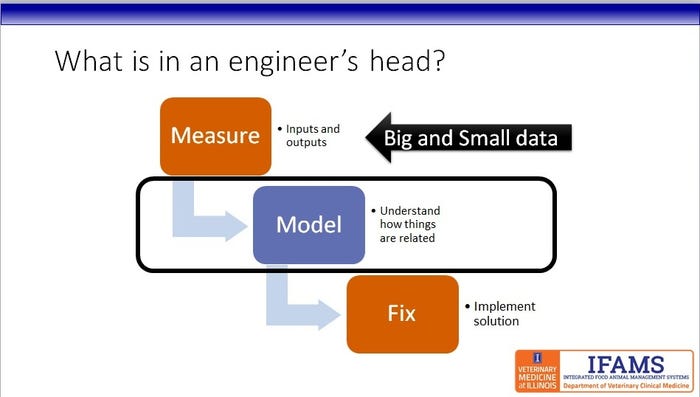

He challenges hog farmers and animal health stakeholders to take a lesson from an engineer’s playbook and execute their three-step fix process — measure, model and fix.

Measure: The first step is to find the voice of the system. Lowe says, “You have to understand what goes into the system and what goes out of the system. You have to figure out what the system is doing.”

Model: Understanding how all the working parts fit together is the next step. It is important to model it mathematically or physically to understand and try potential interventions.

Fix: Finally, the last step is to integrate the solution to solve the problem. Often in animal agriculture production, we just forego the first two steps. Lowe says, “As a practitioner, I am really good at the last bucket – let’s just go fix it today. We tend to think a lot about fix it than how to measure and model those solutions up.”

For all segments of agriculture today, the key to successfully moving forward is big data. However, Lowe warns, “the problem with simple correlation is there are pitfalls. We have to be really careful in looking at this data not to over-interpret, in particular causality, of what is happening there. Applying big data is good, but not perfect.”

In animal health, many significant projects are applying big data, but no one is talking or thinking about it. The challenge with not thinking about is we are not continuously reanalyzing the process to determine if we can do it better and we are perhaps over-interpreting the data, Lowe states.

He further explains that there are gaps in every disease management system and project. Lowe shares his experience with an area regional control project involving a group of producers agreeing to share data intensively.

For instance, neighboring pig farmers agree to control disease by taking certain action based on sharing herd health status. It is making decisions not to put PRRS-positive pigs next another farmer’s sow farm or implementing a vaccination program regional to drive down viral load.

“The challenge to that project is, although it is very intense, it does not have enough scope to necessarily help them answer all their questions,” says Lowe. “It becomes intense short-term execution focus and not long-term strategic focus or even long-term tactically focus to how to make the system better.”

He poses this question, “Will bigger data help solve that problem?”

There are four buckets to leveraging big data: collaboration, aggregation, analysis and synthesis.

Lowe explains, “To make that happen, there are four steps. We have to think about how we aggregate the data and how do we build those collaborations to allow the aggregation to happen. Then, how do we use sophisticated modern tools to do the analysis. Finally, how do we synthesize the information and give it back to producers in a way they can drive decisions by it.”

Moreover, he summarizes, “the ticket to all is we can’t move forward until we know what is going on. We have to measure the system. Thinking about this measurement idea on a macro scale is going to help us drive animal health forward over the long haul at a much faster pace.”

You May Also Like