Can we eliminate Mycoplasma hyosynoviae and Mycoplasma hyorhinis?

Researchers designed a study to determine the effect of herd closure on the prevalence of Mycoplasma hyosynoviae and Mycoplasma hyorhinis.

January 3, 2017

By Maria Jose Clavijo, Iowa State University College of Veterinary Medicine Department of Veterinary Diagnostic and Production Animal Medicine and PIC-Pig Improvement Co., Hendersonville, Tenn.; Alyssa Anderson, University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine; Jerome Geiger, PIC-Pig Improvement Co., Hendersonville, Tenn.; and Wesley Lyons, Bethany Swine Health Services, Sycamore, Ill.

Post-weaning infectious arthritis continues to challenge swine practitioners and producers, costing between $2 and $23 per pig1. Over the last years, veterinary diagnostic laboratories have seen a spike in the number of Mycoplasma hyosynoviae and Mycoplasma hyorhinis-associated lameness cases. In fact, these endemic mycoplasmas accounted for approximately 26% of arthritis cases in 2015 (Iowa State University-Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory data).

Infection with these pathogens compromises animal welfare, creates continuous treatment costs and impacts performance. Control methods include strategic antibiotic therapy and optimizing the pig’s environment via reduction of stocking density, minimizing transport-associated stress, and improving pen design to minimize injuries.2 However, these strategies are not always effective and the situation is compounded by the unpredictability of the outbreaks.

Elimination strategies such as herd closure, strategic medication and vaccination have been shown to be effective at eliminating another mycoplasma, M. hyopneumoniae, through these methods elimination has become repeatable.3 Therefore, a simple question was raised: Can M. hyosynoviae and M. hyorhinis be eliminated via herd closure and antibiotic therapy?

To answer such a question, a study was designed to determine the effect of herd closure on the prevalence of both pathogens. There is currently a lack of information regarding the duration of shedding and changes in the dynamics of infection of MHR and MHS when herd closure is applied.

The study was conducted at a 1,150 farrow-to-finish sow farm with previous history of MHS and MHR associated lameness in grow-finish pigs. The herd was undergoing a M. hyopneumoniae elimination program, based on herd closure and antibiotic therapy. A cross-sectional sampling of sows, piglets and post-weaning pigs was carried out. A total of 462 oropharyngeal swabs and oral fluid samples were collected at five different times post herd closure and tested by polymerase chain reaction. At baseline, OS were collected from 60 sows, 60 gilts, 60 weaning piglets and 30 70-day-old and 130-day-old pigs. Ninety OF were collected from sows, gilts, pre- and post-weaning pigs at 93, 145 and 185 days post herd closure. Finally, 60 OS and 12 OF samples from sows (Parity 1) and 60 OS from weaning piglets were collected at 221 days post herd closure.

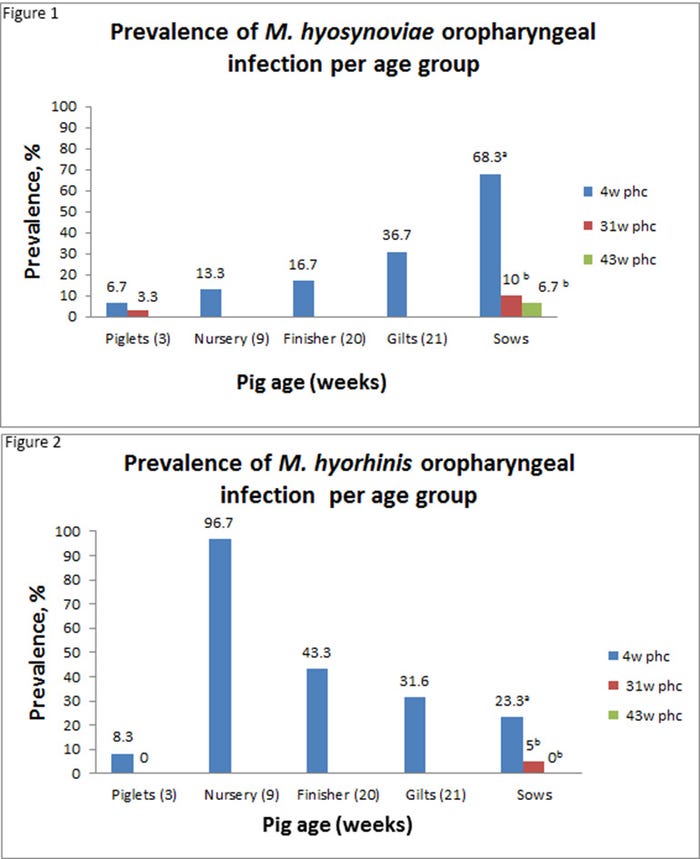

Figure 1: Prevalence of M. hyosynoviae oropharyngeal infection per age group; Figure 2: Prevalence of M. hyorhinis oropharyngeal infection per age group * Values sharing the same superscript are not significantly different from each other (P > 0.05). phc=post herd closure

* Values sharing the same superscript are not significantly different from each other (P > 0.05). phc=post herd closure

The prevalence of MHS and MHR within the herd has been similarly observed in previous studies4,5. Detection of MHS and MHR in oropharyngeal swabs from weaning piglets suggests that pigs become infected from their dams. All 60 nasal swabs collected from 9-week-old pigs at 43 weeks post herd closure were MHS and MHR PCR negative, suggesting a possible reduction in bacterial shedding from their dams. MHS was still detected in sows at 43 weeks post herd closure, suggesting potentially a long shedding period.

On the contrary, MHR was not detected in sows during that time, suggesting a potential effect of herd closure on MHR infection. However, further confirmation of MHR elimination could not be achieved due to the incoming of MHR-positive replacement gilts at the end of the herd closure period. A key component for the success of a herd closure program is to guarantee the infection of all pigs prior to the start of the closure. In this study, it is possible that not all females were exposed to MHS and MHR prior to herd closure. This could have caused a gradual infection of remaining susceptible pigs, thus extending the shedding period of the herd. Further research is warranted to determine the duration of shedding in pigs naturally infected with MHS and MHR. Also, methods for efficacious MHS and MHR gilt exposure should be evaluated. (Figures 1 and 2)

References

1. Waddell, JM. Growing Pig Lameness – A Costly Emerging Issue. 2015. Proceedings of the 6th Annual Meeting of the American Association of Swine Veterinarians. Orlando, Fla.

2. Schmitt, C., 2014. Management of Mycoplasma hyosynoviae. Proceedings of the AASV, 2014 PP 545.

3. Holst et al. 2015. Elimination of Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae from breed-to-wean farms: A review of current protocols with emphasis on herd closure and medication. J Swine Health Prod 23(6): 321-330.

4. Schwartz, J. et al. 2014. Dynamics of Mycoplasma hyosynoviae detection and clinical presentation. Proceedings: 2014 American Association of Swine Veterinarians Conference: Our Oath in Practice, Dallas, Texas. Retrieved from AASV Library Catalog. Pp 115-116.

5. Clavijo, M.J. et al. 2012. Dynamics of infection of Mycoplasma hyorhinis at two commercial swine herds. Proceedings: 2012 Allen D. Leman Swine Conference, St. Paul, Minn. Retrieved from AASV Library Catalog. Pp 91-92.

You May Also Like