Breaking down the SDRS, what it means to the swine producer

Yeske says biggest surprise in the current reporting is that the swine industry has started to turn the corner on PRRSV on grow-finish operations.

November 29, 2022

The Swine Disease Reporting System is a tool developed by a consortium of veterinary diagnostic laboratories in cooperation with the Swine Health Information Center to share information on endemic and emerging swine diseases so veterinarians and producers can make informed decisions on disease prevention, detection and management.

Paul Yeske with the Swine Vet Center says that the monthly SDRS reports allow the swine industry to monitor trends and predict when herds might be at a greater risk of an outbreak.

The SDRS – led by the Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory with participation from the University of Minnesota Veterinary Diagnostic Lab, the South Dakota Animal Disease Research & Diagnostic Laboratory, the Kansas State Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory and the Ohio Animal Disease & Diagnostic Laboratory – helps veterinarians better understand the epidemiology of particular pathogens moving among swine populations, Yeske says.

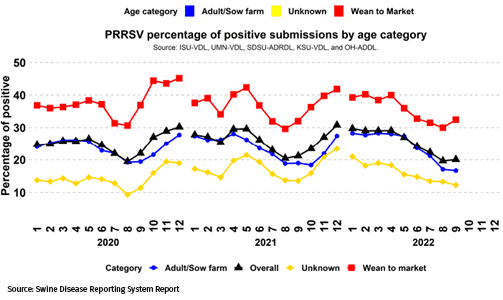

For example, in the last four years, whenever there has been an increase in porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus activity in grow-finish units, there tends to be an increase in positive cases in sow herds a month later. So, when PRRSV activity is trending up in the grow-finish barns, nearby sow farms may want to make sure they're doing everything possible relative to their biosecurity protocols to reduce the risk of the virus spreading into nearby sow units.

(This is the breakdown of the different phases of production showing the turn up in PRRS in wean to finish.)

SDRS also reports data on a geographic basis, so users can look at what regions are hotspots for a disease and then act accordingly to minimize pathogen spread, he says.

Yeske likes to compare the monthly SDRS report against the weekly Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Project reports because they use different approaches to examine data. "The Morrison project is based on farms reporting clinical signs they're experiencing, while SDRS uses diagnostic data from university veterinary labs," says Yeske. It is interesting to see it from two different perspectives can identify similar trends.

He notes that the SDRS has a bias in that it is based on diagnostic data, so the data is derived from people looking for a problem, but it is still valuable to look at as an industry because at least you know what people are out looking for and then what they're subsequently finding when looking at a particular population.

SDRS also reports viral sequencing, so users can compare the virus strains they're dealing with in their herd compared to what is circulating in the broader industry, Yeske says, noting that more recently, PRRSV strains 1-4-4, 1-7-4 and 1-8-4 have been the top three viruses circulating, along with the vaccine virus.

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus, mycoplasma and influenza are also tracked by SDRS. "PED incidence has been occurring more in the January time frame, so producers can be aware and start to monitor for early signs of the virus as winter approaches," Yeske says. "Similarly, mycoplasma tends to drop off in the summer and go up in the winter, so steps can be taken to reduce the risk of mycoplasma entering a herd and hopefully head off any outbreaks before they happen."

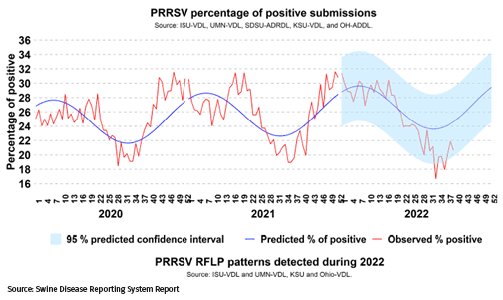

The SDRS predictive model is based on the three previous years with some statistical analysis, Yeske explains. In the report, for each pathogen, there's a shaded zone where the report authors believe normal activity should be, so if the trend line jumps out above that shaded zone, there's more activity going on, or if it drops to the underside, there's less activity.

Surprises

Yeske says the biggest surprise in the current reporting is that the swine industry has started to turn the corner on PRRSV on grow-finish operations. In the previous few years, PRRSV has started to increase in grow-finish in August and early September, but this year, the virus has held off until September.

For PED, he says there was more activity last winter and spring, but that went back under control over the summer, so the overall PED numbers have come down and "we'll have to see what happens this winter."

Long-term value

Yeske says the long-term value of reviewing the monthly SDRS reports is the ability to get that predictive interpretation and to see what is happening across the swine industry, not just in a single herd or system. "Sometimes, it feels like you're the only one that's breaking (with a disease), and well, the reality is a lot of herds are breaking, so there is value in understanding what is going on with the rest of the industry," he says.

On the SDRS website, Iowa State also has a dashboard that allows users to dial in and take a closer look at the data and proactively notice trends in a particular geography for a particular pathogen. These tools can help users maintain awareness of pathogens that are affecting their herds but may not be getting industry-wide attention.

Yeske noted that last winter, the SDRS reports showed increased activity of acute pleuropneumonia, which hadn't been seen for a while but was spreading among grow-finish operations.

There is value in accumulating diagnostic information, Yeske says, because SDRS brings together data from multiple sources and puts them in a single place where additional analytics can be applied to create better disease management tools. In the past, these data were in individual research projects or individual reports that stakeholders would need to search for, but now, with the SDRS dashboard, users can view the monthly report and get a summary of what is happening across the industry.

Deeper diagnostics

In addition to the surveillance data from PCR sampling for influenza, mycoplasma, PRRSV and PED, the SDRS reports also look at tissue cases – where the diagnostic labs do more specific tests on submitted tissue samples, Yeske says. These tests show everything that is found in a particular sample and how those relate to each other. For example, on enteric cases, is the most common pathogen rotavirus, an Escherichia coli or a clostridium? And because of the overlap many cases have, which is more dominant, and which may be secondary infections?

Typically, when a veterinarian sends in a tissue sample, he/she is trying to solve a health challenge that needs more diagnostics than ongoing monitoring may provide.

Overall, the value of tools such as the monthly SDRS report is to provide producers and veterinarians information on the disease trends occurring across the swine industry and within particular geographies so that they can make informed decisions about disease prevention and management.

Source: Swine Vet Center, which is solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly owns the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like