Animal movements: The Achilles heel for PRRS management

Since animal movements are unavoidable, strict biosecurity measures are needed to mitigate risk associated with indirect connections between farms.

June 8, 2020

The U.S. swine industry continues to face numerous challenges to its production and economic growth. Among the foremost challenges are infectious diseases that are endemic to the United States, as well as the ever-growing threat of introduction of foreign animal diseases. One of the more important endemic diseases in the United States is porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome. With an economic impact of over $600 million per year, it is clear that any efforts to mitigate the disease would have considerable economic benefits.

In an effort to understand the spread and persistence of PRRS within the U.S. swine population, researchers at the University of Minnesota have investigated pathogen transmission pathways, local area versus long distance spread between farms, drivers of PRRS virus genetic diversity and evolution, and animal movement networks. We recently compared the relative importance of spatial proximity versus animal movements in driving PRRS spread between farms. From this study, it was evident that although local area spread for farms within less than 5 kilometers of each other was epidemiologically important, we found that most of the viral spread was related to farm contacts via animal movements1.

Despite the risks associated with animal movements, this risk is inescapable in vertically integrated swine productions systems. Given that animal movements are tied to the industry's vulnerability to disease introduction and spread, we further investigated the stability of animal movement networks as well as their role in PRRS spread utilizing data from farms participating in the Morrison Swine Health Monitoring Program.

Using animal movement data from over 2,000 farms in the United States between 2014-17, we show that an infection chain originating from a single farm can be expected to reach approximately five other farms within six months, on average, but these animal movement chains can reach upwards of 650 farms in extreme cases. In this latter case, approximately 25% of the farms in the network would be impacted, which demonstrates how the presence of "super-spreader" farms within the network may contribute to rapid disease spread via animal movements.

Quantifying a farm's contacts via animal movements over a span of about six months provided a stable picture of the farm's network connectivity and can be informative in the identification of high-risk farms and potential super-spreaders, which would enable more focused interventions.

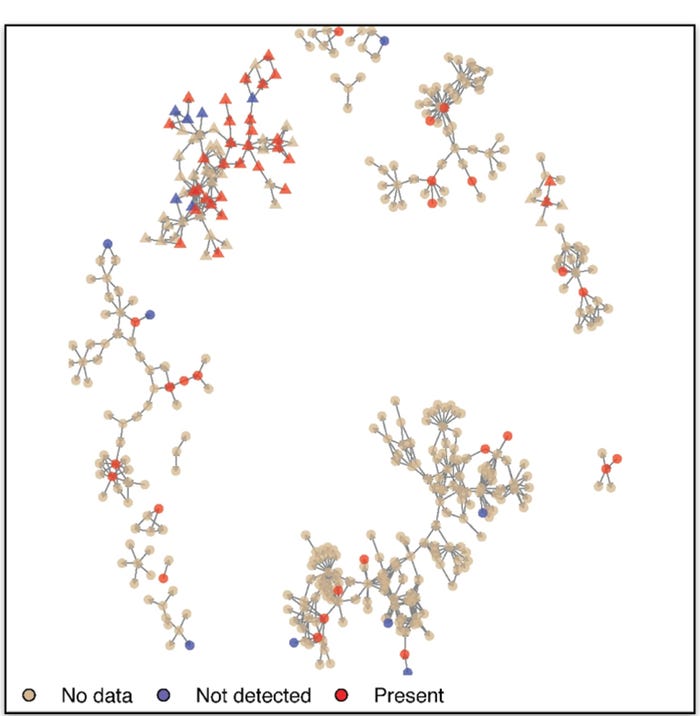

In order to evaluate how animal movements, relate to the spread of PRRS viruses in the 1-7-4 family (referred to here as Lineage L1A, Figure 1), we linked the movement data with over 1,800 ORF5 PRRS sequences collected from the farms. Overall, the risk of L1A occurrence in a given farm increased not only as a result of direct contact with an L1A-positive farm, but also increased as a result of indirect connections (contact of a contact) with L1A-positive farms.

Moreover, farms that engaged in more outgoing movements also experienced higher risk. This suggests that the risk due to animal movements is not only associated with movements of infected animals to the destination, but also from potential movement-related breaches in biosecurity in the origin farm.

In summary, there is a considerable risk of disease spread via animal movements. Since animal movements are unavoidable, strict biosecurity measures are needed to mitigate risk associated with indirect connections between farms. Similarly, adoption of more systematic monitoring of health status of all farms, combined with maintaining digital records of animal movements, would enable better preparedness and more focused disease control measures. These approaches could also help to identify high-risk farms and reduce the length of between-farm infection chains. Such a framework would be beneficial in the management of both endemic and foreign animal diseases.

Reference

1K. VanderWaal; I.A.D. Paploski; D.N. Makau, and C.A. Corzo, "Contrasting animal movement and spatial connectivity networks in shaping transmission pathways of a genetically diverse virus," Prev. Vet. Med., vol. 178, no. March, p. 104977, May 2020.

Sources: Dennis Makau, Igor Paploski, Cesar Corzo and Kimberly VanderWaal, who are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like