Relative risk of transmission of ASF in imported soybean products

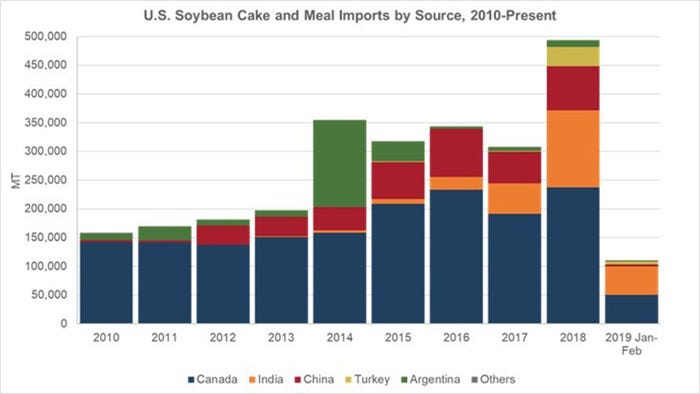

Although the proportion of soybean meal imported from China steadily increased through 2018, the quantities appear to have declined by approximately 94% in 2019.

August 8, 2019

By Jerry Shurson and Pedro Urriola, University of Minnesota

African swine fever continues to be a significant threat to U.S. pork production, as well as corn and soybean growers. The introduction of a foreign animal disease may cause the U.S. losses of about $8 billion for the pork industry on the first year of an outbreak (Hayes et al., 2011; Lusk, 2019). However, the economic impact of an ASF outbreak would extend beyond the pork industry because the prices and revenue from production of corn ($ 44 billion) and soybeans ($25 billion) would also significantly decrease as a consequence of decreased utilization of these ingredients in swine diets (Hayes et al, 2011).

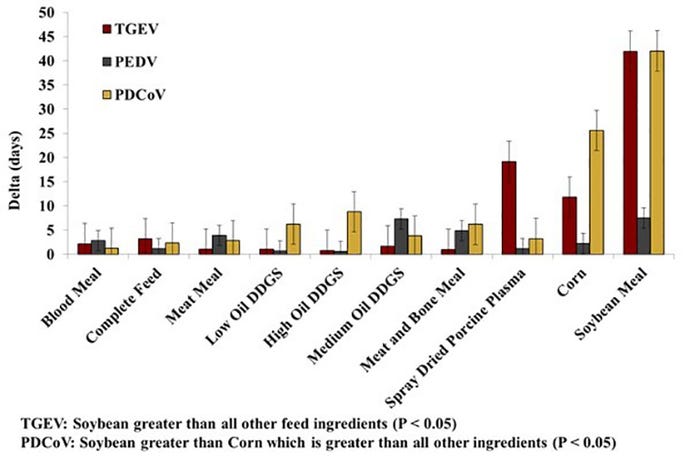

Most swine viruses tested in the Pacific and Atlantic transboundary models survived in soybean meal (Dee et al., 2018). In addition, porcine coronaviruses had the greatest survival in soybean meal compared to other feed ingredients (Trudeau et al., 2017). These observations suggest that if contaminated soybean products are a potential source of virus introduction. Fortunately, almost all of the U.S. pork industry uses soybean meal and related soybean products from the domestic soybean supply chain, which represents negligible risk as long as it is not cross-contaminated. In addition, about 98.9% of soybean meal produced in the U.S. is produced by solvent extraction which steps are likely to inactivate the ASF virus. These steps are conditioning (150 degrees Fahrenheit for 15 minutes), extraction (145 degrees Fahrenheit for 30 minutes), desolventizing/toasting (150 degrees Fahrenheit 10 minutes), and dryer/cooler (220 degrees Fahrenheit for 45 minutes).

Imports of soy-based products

Historically, small quantities of soy products have been imported into the U.S. (Figure 2). However, there are significant discrepancies in feed ingredient import data and specific country of origin from various government and other data reporting sources. China is the only ASF-positive country that exports soybean meal to the U.S. Although the proportion of soybean meal imported from China steadily increased through 2018 (about 100,000 metric tonnes), the quantities appear to have declined by approximately 94% in 2019 according to newer data from the USDA Economic Research Service. Soybean meal imports from China and India are primarily organic soy products, which fill a market void due to limited domestic organic soybean meal production to meet demand for organic livestock and poultry production. A search of the Port Import/Export Reporting Service data suggest that the vast majority of soybean products entered the U.S. via the port of Oakland, Calif. However, it is unclear how much of imported soybean products may be used for human consumption or organic fertilizers. Likewise, organic soybean imported from Turkey is most likely not exclusively from Turkey, but rather from countries in the Black Sea region, which may also be a risk factor.

It is important to note that there has been no sampling or testing of imported feed ingredients into the U.S. to show any evidence that the ASF virus may be present. However, because the ASF virus has been shown to survive in soybean meal during experimental trans-Pacific and trans-Atlantic shipment modeling conditions, and the potential for it to be present in imported soy products, the University of Minnesota African Swine Fever Response Team and the Swine Health Information Center conducted a stakeholder workshop on July 10 to accomplish the following objectives:

Identify and discuss the various segments and potential risk factors of the soy supply chain in North America.

Identify and discuss potential prevention, mitigation and product differentiation (country of origin) strategies for soy products used in the U.S. pork industry.

Identify research and education needs related to foreign animal viruses and soy products.

Canada’s approach to ASF prevention in imported feed ingredients

The Canadian government has developed and implemented programs and requirements on imported animals and meat. These programs and requirements are based on a risk assessment of foreign travelers and importation of food and feed ingredients. The risk of ASF virus transmission in grains, oil seeds and associated meals were ranked high because of the risk of cross-contamination (housed outside, exposed to weather and potential for manure exposure). Although the volume of imported feed ingredients into Canada is relatively small compared to the U.S., the Canadian government implemented control zone capabilities to regulate the imports of these products. There is a requirement for importers to declare the end use of the products, which allows tracking of imported ingredients. In addition, a questionnaire was developed and implemented for feed ingredient importers (CFIA, 2019a).

A government order was implemented in March 2019 indicating that any feed products (grains or oilseeds) coming from countries with active ASF during the past 5 years (in domestic or wild pigs) were put on an alert list and is available online (CFIA, 2019b). This regulation did not result in a complete ban on imports from ASF infected countries, but led to imposing required holding times for imported feed products or applying a specified heat treatment. If importing ingredients from countries on alert list (only for international seaports), grain, oilseeds and associated meals must be held in Canada at 68 degrees Fahrenheit for 20 days for 50 degrees Fahrenheit for 100 days at an inland warehouse. Use of extended holding times were difficult to implement because of the high volume of ingredients and ability to maintain the specific temperatures. Heat treatment can also be applied either in country of origin or in Canada at temperatures of 158 degrees Fahrenheit for 30 minutes or 180 degrees Fahrenheit for 5 minutes. However, use of heat treatment is also challenging because of negative impacts of high heat on amino acid digestibility and loss in nutritional value of vitamins. Imported grains and other feed products cannot be held at the port, but must go directly to an inland facility for holding. Because of low volume of imported feed ingredients, the negative effects have been fairly minor. The lessons learned from this approach is to encourage biosecurity and buyer awareness as the first line of defense to prevent ASF virus introduction.

References

CFIA. 2019a. Facility questionnaire for the import of unprocessed/raw grains and oilseeds in Canada. Available: http://www.inspection.gc.ca/animals/terrestrial-animals/diseases/reportable/african-swine-fever/facility-questionnaire/eng/1553626801594/1553626857123. Accessed: August 6, 2019.

CFIA. 2019b. Importers: Understanding feed controls to prevent African Swine Fever. Available: http://inspection.gc.ca/animals/terrestrial-animals/diseases/reportable/african-swine-fever/importers/eng/1556047524324/1556047524554. Accessed: August 6, 2019.

Lusk, J. 2019. Potential economic impacts of African Swine Fever (ASF). Available: http://jaysonlusk.com/blog/2019/8/5/potential-economic-impacts-of-african-swine-fever-asf. Accessed August 6, 2019

Dee, S. A., Bauermann, F. V., Niederwerder, M. C., Singrey, A., Clement, T., de Lima, M.,… Diel, D. G. (2018). Survival of viral pathogens in animal feed ingredients under transboundary shipping models. PLOS ONE, 13(3), e0194509. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194509

Hayes, D., Fabiosa, J., Elobeid, A., & Carriquiry, M. (2011). Economy Wide Impacts of a Foreign Animal Disease in the United States.

Trudeau, M. P., Verma, H., Sampedro, F., Urriola, P. E., Shurson, G. C., & Goyal, S. M. (2017). Environmental persistence of porcine coronaviruses in feed and feed ingredients. PLoS ONE, 12(5). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0178094

Shurson is a professor of swine nutrition and Urriola is a research assistant professor in the Department of Animal Science at the University of Minnesota.

Sources: Jerru Shurson and Pedro Urriola, who are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like