Using sun to keep sows cool

Morris research farm is testing innovative energy practices in swine production.

August 2, 2017

By Liz Morrison

Here’s an idea: Let the summer sun keep sows cool!

Researchers are testing that idea in a new study at the University of Minnesota West Central Research and Outreach Center in Morris.

A 20-kilowatt solar photovoltaic array will power an electric heat pump system that circulates cool water under metal floor mats in the farrowing stalls. Scientists hope the 70-degree-F flooring will keep mother pigs cool in the same way that under-floor heating systems warm our houses, said Lee Johnston, WCROC swine scientist. Johnston spoke at the 2017 Midwest Farm Energy Conference this summer.

More efficient sow cooling is just one of the innovative energy-related practices that are being tested at the Morris research farm. Other ideas include more efficient piglet heating systems, reduced nocturnal temperatures and generating solar power on-site to run the barns.

The work is part of a long-term effort to reduce fossil fuel use in livestock production — an effort that is being driven by consumer demand.

“Consumer food supply chains are asking for reduced environmental impacts,” Johnston said.

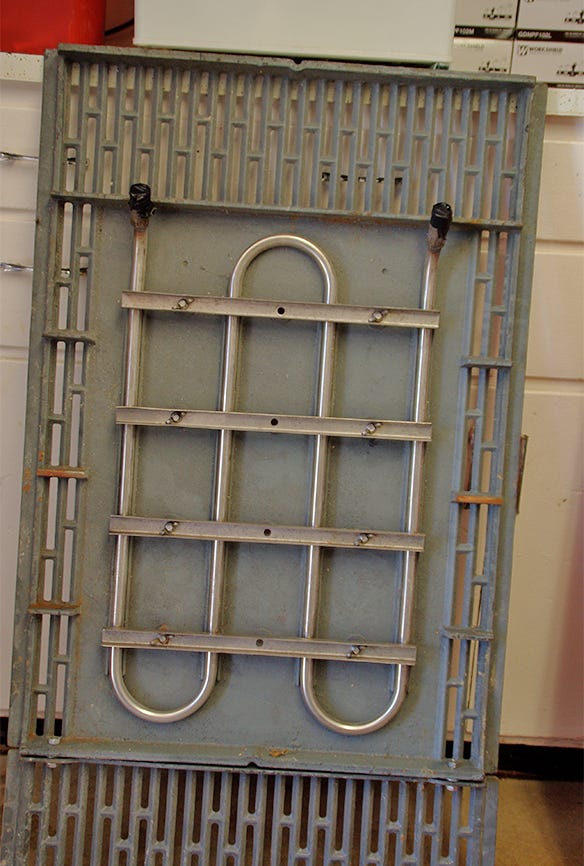

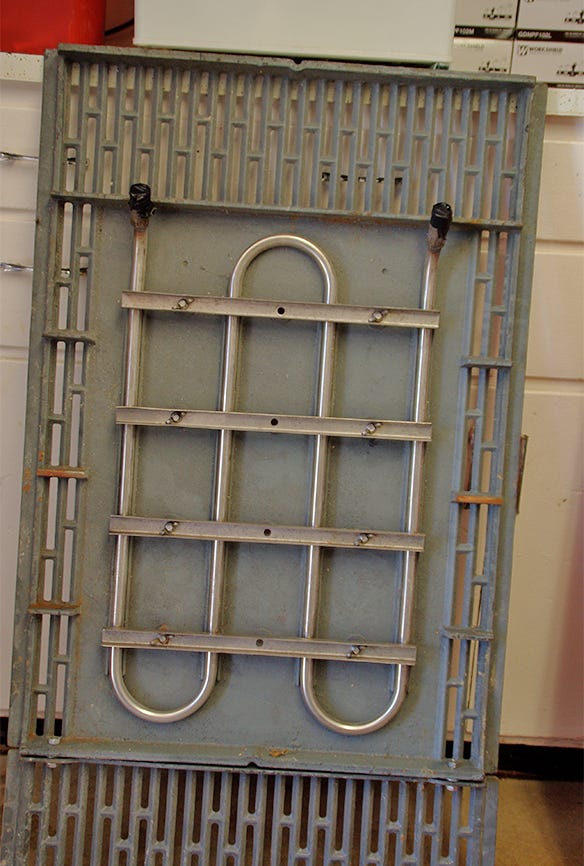

HEAT TO COOL: A solar photovoltaic array powers a heat pump system that circulates chilled water through the floor mats at the WCROC in Morris . The same system will be used to heat creep mats for baby pigs. (Lee Johnston, University of Minnesota)

Keeping pigs comfortable in summer

These days, pigs are more sensitive to heat than they used to be, said Mike Brumm of Brumm Swine Consultancy Inc., in North Mankato, another conference speaker. That’s because pigs nowadays deposit more lean muscle than a decade ago, and therefore produce more body heat. A 280-pound pig, for example, generates close to 1,200 British thermal units of heat per hour, Brumm said. Lactation generates extra heat, too.

Drip cooling is often used to help farrowing sows cope with summer heat, Johnston said, but it's messy, and the constant wetness encourages disease.

“We expect that water-cooled flooring will keep sows dry and comfortable,” Johnston said.

WCROC also plans to use its solar-powered heat pump system to chill lactating sows’ drinking water to about 55 degrees F. This helps to cool the pigs from the inside, just like a glass of ice water refreshes you on a hot day. Korean researchers found that heat-stressed sows increased water intake by more than 20% and feed intake by 40% when their drinking water was cooled from 72 degrees F to 59 degrees F, Johnston said.

The same solar-powered heat pump system will also be used to warm up water-heated creep mats for piglets. The warm mats keep the baby pigs’ comfort zone at a steady 108 degrees F without energy-gobbling heat lamps.

Heat pump systems are an efficient way to regulate the temperature of pigs’ environments, Johnston said, allowing a cool environment for the sow and a warmer environment for her piglets in the adjoining stall. However, one drawback of circulating water to cool and warm pigs is all the plumbing required, he noted.

The research was slated to begin this summer.

Nighttime temperature setbacks

WCROC is also investigating ways to cut energy costs in swine barns during the winter. The average cost of heating Minnesota swine barns ranges from $1.37 to $1.92 per pig, according to data from the Adult Farm Business Management program.

Lowering the barn temperature at night is an easy way to cut fuel consumption, Johnston said. Reduced nocturnal temperatures (RNT) is an older idea that has now become practical, with improved barn designs, and automatic furnace and ventilation fan controllers, he said.

Pigs actually prefer to be cooler at night, Johnston said. In an experiment where pigs were taught to turn on a heat lamp, they chose lower nocturnal temperatures.

In two experiments to see how RNT affected pig performance and fuel consumption, Johnston’s research team lowered the target room temperature in the nursery barn between 7 p.m. and 7 a.m. Over the course of the evening, the barn temperature gradually dropped.

In the first study, researchers lowered the desired temp by 10 degrees F at night, compared to the daytime setting. RNT had no effect on pig morbidity or mortality, average daily gain, feed intake or feed-to-gain ratios, compared to the control groups, Johnston said. Meanwhile, heating fuel use in the RNT groups dropped 18%, and electricity use fell 9%, he said.

In a second study, researchers lowered the desired nighttime temperature by 15 degrees F — with the same results. Overall pig performance was unchanged, while fuel consumption fell by almost 30% and electricity by 19%. That saved about $1.73 per pig.

And in terms of greenhouse gas emissions, the savings amounted to 15.5 pounds of CO2 per pig, Johnston said — a savings that could be a marketing advantage.

Morrison is a freelancer based in Morris.

You May Also Like