Going global, acting local

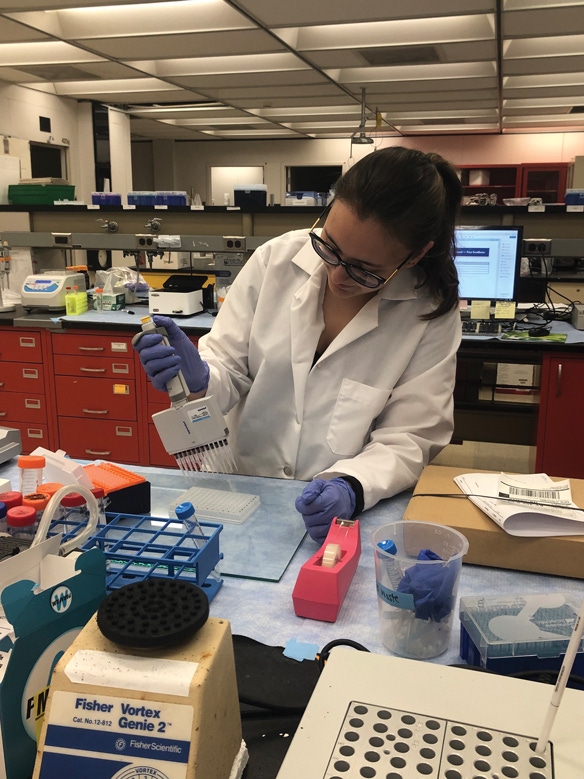

University of Minnesota doctoral student puts on miles with swine feed research.

In just eight short years, Michaela Trudeau has probably accomplished more than many in the swine industry could even fathom tackling in that amount of time.

“If you would’ve told me, when I started my undergrad in 2011, that this is where I would be, I would have laughed,” Trudeau says. “I don’t have any regrets. I love working in the animal science industry, and I love working with pigs.”

Working with pigs isn’t second nature for the doctoral student, who grew up in the suburbs of St. Paul, Minn., but she caught up quickly once she stepped onto the University of Minnesota campus in 2011.

She’s determined the survival kinetics of coronavirus in various feed ingredients, the nutritional and physiological responses of feeding rapeseed to growing pigs, and that antibiotic feeding does modify bile acid metabolism. Her research has taken her miles away from the U-M Golden Gophers lab to Missouri, Norway and Australia, all while maintaining a strong commitment to several student organizations across the Midwest.

“Mickie is a unique and exceptional graduate student in many ways. She grew up in the Twin Cities metro area with no traditional swine background, but is passionate about animals and science,” says Pedro Urriola, research assistant professor at the U-M Department of Veterinary Population Medicine and co-adviser to Trudeau.

“Her inquisitive nature, leadership, international experiences and passion to apply basic science in solving today’s challenges of feeding the world sustainably make her unique among the next generations of swine scientists,” Urriola says.

For these contributions and the many more she will potentially make, Urriola says Trudeau is one of the global pork industry’s rising stars.

Backyard beginnings

Trudeau grew up in Inver Grove Heights, Minn., where her family didn’t have land but did have horses.

In addition to loving animals, Trudeau also had a passion for science and at one point, wanted to be an equine veterinarian. However, one of the things she had always been told about getting into veterinary school is that it is competitive for equine, and getting some livestock production experience would help.

Despite living in town, Trudeau talked her parents into letting her raise chickens for 4-H, and soon her family’s backyard was home to 40 to 50 birds at a time.

“We’re lucky our neighbors were nice, and we gave everyone eggs, but I liked it,” Trudeau says. “I wasn’t raised on a farm, but I tried my very hardest to make that house a farm.”

That experience with chickens paid off. Shortly after starting her undergraduate studies, Trudeau began working in the poultry nutrition laboratory under the direction of Sally Noll, a professor in turkey nutrition at U-M. The young student enjoyed the research and realized a future in equine veterinary medicine was no longer part of her future aspirations.

“As much as I love my horses, I don’t love everybody else’s horses as much; and No. 2, I realized how much I liked working in agriculture, and I just loved being in the poultry nutrition lab,” Trudeau says.

From poultry to PEDV

Trudeau continued to work in the poultry nutrition lab for three more years. It was during one of her final meetings with her undergraduate adviser, Jerry Shurson, also a professor of swine nutrition at U-M, that Trudeau mentioned that she really enjoyed the poultry research but would like to broaden her horizons more.

The timing was impeccable, as U-M had recently received funding from the National Pork Board to study the survival of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus in animal feed.

“It all happened really fast, and I started working in the virology lab on this project on PEDV — and that kind of started my involvement in the swine industry,” Trudeau says. “The industry had all of the things that I loved about the poultry industry, just when you get into the agriculture side of things, and I have been there ever since.”

The objectives of the study were to measure the effect of thermal treatment on inactivation kinetics of the PEDV in nine commonly used feed ingredients — including three types of dried distillers grains with solubles — and to determine the PEDV inactivation kinetics on various equipment and facility surfaces.

Trudeau, working under Sagar Goyal, a professor in the U-M Department of Veterinary Population Medicine, led the study and hypothesized that different chemical characteristics of the feed ingredients would affect PEDV survivability when subjected to different thermal treatments, and PEDV inactivation would differ among material surfaces.

The results of the study showed that PEDV survival among the nine feed ingredients evaluated was not different when exposed to thermal treatments for up to 30 minutes. However, different combinations of temperature and time resulted in achieving a 3- to 4-log reduction of PEDV in all feed ingredients evaluated. Finally, PEDV survival was similar on galvanized steel, stainless steel, aluminum and plastic.

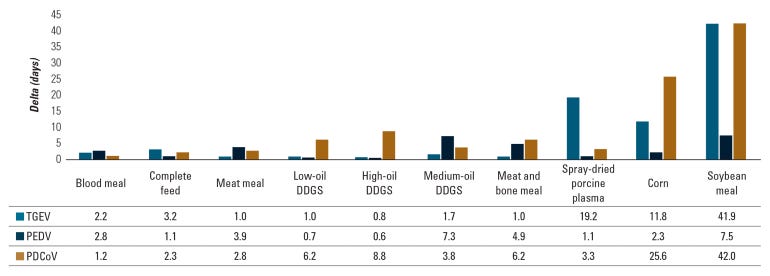

At the same time, Trudeau was involved in another study (Chart 1) funded by NPB that measured the survival time of PEDV, transmissible gastroenteritis virus and porcine delta coronavirus in complete feed and feed ingredients. Survival time of TGEV and PDCoV was greatest in soybean meal, which was consistent with previous research results showing that PEDV has a very high survival in soybean meal (Dee et al., 2015).

“We tried to figure out why the virus survives so well in soybean meal, and we couldn’t come up with any groundbreaking conclusions. We did find a correlation with the moisture content of the ingredients, with ingredients with higher moisture content tending to have better virus survivals, but that was about the best conclusion that we could make,” Trudeau says. “It’s interesting. I just saw one paper also written by Scott Dee on the survival of pathogens during transboundary shipping that shows African swine fever virus seems to survive in soybean meal, so there might be something there to look at into the future.”

The research also included testing a variety of different feed processing conditions, different feed additives and even irradiating the feed.

“In general, we found that most feed processing was able to cause a decrease in survival of PED, but to varying degrees,” Trudeau says. “For feed additives, there are a few products that were able to cause a greater inactivation of the virus compared to others; and generally, regarding treatments, the virus doesn’t survive very well under higher heating conditions, and the irradiation treatments were also very effective.”

Broadening her horizons

While Trudeau was pursuing her master’s degree, another research opportunity opened — but not so close to home.

“Dr. Shurson told me, ‘I have this project in Norway, and I really think you’d be a good fit.’ I didn’t even have a passport. I’ve always been a bit of a homebody, so I’ve never traveled that far,” Trudeau says. “At the time I was thinking ‘Just don’t cry, get out of the office. I can figure it out.’ It was such a good opportunity, though; I couldn’t miss it.”

Three weeks later, with an expedited passport in hand, the 21-year-old was on her way to the Norwegian Life Sciences University to work on a collaborative research program focused on determining the nutritional and physiological responses of feeding rapeseed to growing pigs. During her three months there, Trudeau examined the digestibility of rapeseed, metabolites and redox (oxidation-reduction) balance when rapeseed is fed, and how rapeseed may be impacting the choline intake and metabolism in pigs.

“I’m really glad that I had that opportunity, even though it was scary. It definitely was worth it — and now, it’s like, you get the travel bug: ‘I want to go here and here,’ ” Trudeau says. “I’m really thankful my advisers have always been ones that know when to give me a push and when to lay off, so it was nice. I think I needed that, and it was a really good opportunity.”

That experience in Norway, along with her research on PEDV solidified Trudeau’s strong interest in science. Instead of pursuing studies in veterinary medicine, she decided she wanted to stay in swine nutrition research and pursue a doctorate.

Antibiotics and bile acid

Upon returning to the States, Trudeau wasted no time getting started on her Ph.D. studies. Her first research project involved digging into feces samples from a 2012 study on fecal microbiome in pigs treated with or without antibiotics.

“I was talking to another grad student on the bus to one of the classes we were taking together, and he’s telling me about these samples,” Trudeau says. “We were like, we should also do metabolomics analysis on these samples — and maybe we could correlate the microbiome results that they already had, but with metabolomics results.”

Microbial metabolites are expected to be key mediators between antibiotics-induced microbiome changes and growth-promoting effects. The objective of the study was to extend the identification of tylosin-responsive microbes to the identification of tylosin-responsive metabolites in growing pigs.

The multivariate model of LC-MS (liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry) data showed that time-dependent changes occurred in the fecal metabolome of both control and tylosin-treated pigs. More importantly, the metabolomic profiles were similar between the tylosin treatment and control groups in weeks 10 and 22, but diverged during weeks 13-19.

Subsequent analyses of the fecal metabolites contributing to the separation of two groups of pigs showed that hyodeoxycholic acid was greatly increased during weeks 13-19 (P < 0.05) in the group of pigs fed tylosin. The integration of current metabolomics data and the microbiome data from a previous study revealed the consistency between HDCA and a specific genus of microbes in the Clostridia family.

“We were able to find a correlation between bile acid production in the pigs that were treated with antibiotics versus not antibiotic-treated, and then we were able to correlate that to a specific bacterium, she says.

“It’s interesting, because there’s a lot of papers now that are investigating the mechanism of action for the subtherapeutic levels of antibiotics, and others are also suggesting that it is heavily linked to bile acid production,” Trudeau says. “It was cool. It was old data, and we only had feces, so our conclusions were limited; but we were still able to make that connection.”

That research once again put Trudeau back on a plane — this time halfway around the world. In August 2018, she was invited to present those data at the Symposium for Digestive Physiology in Pigs in Brisbane, Australia.

“It was really good. It’s amazing how we used antibiotics for so many years, and nobody really thought about how they worked. When you go through the literature, there’s literature that shows that these antibiotics caused growth promotion effects, and there’s a lot of benefits on the research side,” Trudeau says.

“Now that we’re looking for alternatives, well, maybe we should go back and dig more into why they were working and how they were working. Having that link to the bile acids, especially with some of the other people doing research in the area, it’s always fun when you do an experiment and get results — and then someone else’s results are similar.”

Microbiome, gene expression

Her current research involves a unique partnership with Land O’Lakes-Purina Animal Nutrition, where Trudeau has spent time studying the mechanisms of growth responses of feed additives in nursery pig diets at the firm’s research farm in Gray Summit, Mo.

“That was a really good experience to see on the commercial side, how they do research; and they have this fantastic research facility that was so fun to be in,” Trudeau says

“We took a ton of different samples, and we’re doing metabolomics analysis to look at some of the metabolites that may be different when we’re feeding either antibiotics or some of their products that they’re testing out. And then also, we’re trying to correlate that to changes in the microbiome.”

Similar to Trudeau’s last study on the different metabolites produced and coinciding with a specific bacterium present, now the research is adding a third piece to the puzzle and looking at gene expression.

“We want to tie this together — metabolites, bugs in the microbiome and the genes that are active at that time — to see if we can kind of make a pathway,” Trudeau says. “It gives us a much bigger picture idea of what’s actually happening in the animal, because we’re looking at all of these different moving pieces.”

Local leadership

When Trudeau is not in the barns or in lab, she’s participating in several student organizations across the Midwest as president of the U-M Animal Science Graduate Club, coordinator of the Minnesota Targeting Excellence Scholarship Program and graduate student representative on the Midwest section of the American Society of Animal Science board of directors.

“It’s a really good opportunity to just spend time with other grad students, because grad school sometimes can be tough. So, it’s nice to have events like this and be involved with clubs where you’re just with other grad students who understand what you’re going through.”

Reflections, aspirations

Trudeau hopes to complete her doctorate in December, and while she doesn’t have a job lined up upon graduation, she says she would like to stay in research — but through the industry rather than academia. She’s also open to more international travel.

“I really like being on-farm, and I really liked talking to producers and being involved there, so I can also see myself in that type of role, in research or technical services; but I love everything,” Trudeau says.

“I could see myself being the person who, 30 years down the road, having like four different jobs in the industry that are all very different. But I love animals, so I’m definitely going stay in the animal science industry,” she says.

Trudeau credits her advisers Shurson and Urriola for helping her reach her potential.

“They’re really good at setting me up for good opportunities, but also not doing it for me,” Trudeau says. “They’ll point you in the right direction and be like, ‘Nope, you can do this. No, go ahead, go get this done.’ It’s amazing to look at how far I’ve come just from them pointing me in the right direction.”

She also says she is grateful for Brenda DeRodas, director of swine research at Purina Animal Nutrition Center, who has been very helpful to Trudeau in exploring potential industry career opportunities that could complement her research.

Of course, Trudeau says it all goes back to her parents and the backyard chickens they let her have.

“My parents have always been such troopers. I mean, I didn’t grow up on a farm, but they’ve always been so supportive on ‘This is the direction you want to go.’ ‘OK, you want to show chickens, we’re going to figure it out, and we’ll get chickens today,’” Trudeau says.

“I kind of drug them into this world that they knew nothing about, and they’ve been really good at supporting me no matter what.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like