Contract Production, Genetic Insight Added to Industry’s Milestones

Last week’s discussion of pork industry milestones elicited a number of e-mails and calls from readers, most of which suggested that I may have missed a few milestones on the journey.

December 3, 2012

Last week’s discussion of pork industry milestones elicited a number of e-mails and calls from readers, most of which suggested that I may have missed a few milestones on the journey. At the risk of milestones becoming kilometerstones (for my fellow non-metric Americans, a kilometer is about 0.6 miles), this week I offer a few additions:

Milestone No. 6 – contract production. This concept had been around for a long while in the poultry business, but was applied to hogs in the 1970s in North Carolina, I believe. Eldon Juhl built the first large contract production network in Iowa and later sold it to Murphy Family Farms to form that North Carolina company’s first foray into the Corn Belt. Contract production was not so much a new way to raise hogs as it was a new way to finance hog production by getting someone else to put up the capital needed for a major portion of the production enterprise – the land and buildings. If these “growers” were chosen carefully and meaningful incentives were established, the “integrator” or “contractor” could also get skilled caregivers for their animals in the deal. Investing $1 million in a complete hog farm might have gotten you 650 sows, farrow-to-finish. But investing $1 million in breeding stock and operating equity could have gotten you five times that many sows in a farrow-to-wean operation coupled with contract finishing. While used for all phases of production, finishing has always been where contracting worked best. A side benefit, or course, was geographical dispersion of the production enterprise, making multi-site production much easier, reducing the risk of a disease-related catastrophe and putting waste nutrients into areas where they were more useful and valuable.

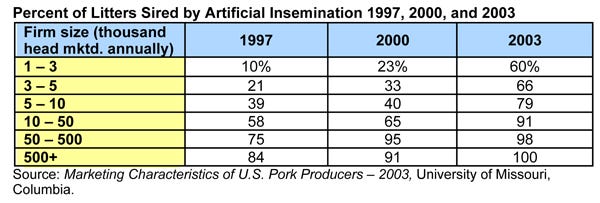

Milestone No. 7 – NPPC’s Genetic Evaluation Project. This was a hugely controversial effort by the National Pork Producers Council (NPPC) to use Pork Checkoff funds for research to identify superior genetic lines. Some characterized it a colossal waste of money because it would take too long, making the results more a history lesson than anything else. Proponents cited the complete lack of third-party comparison of genetic lines, especially those offered by commercial genetic companies. I won’t argue the results or their usefulness, but my proposition is this: The project indelibly changed the U.S. pork industry by demonstrating the ease and usefulness of early weaning (Milestone No. 2 last week’s Weekly Preview) and artificial insemination (AI). Recall that the project signed up cooperating commercial producers across the country and provided semen for them to breed sows on their farms. It then gathered specified numbers of early weaned pigs from those litters and placed them in common grow-finish buildings where production figures were gathered and carcass characteristics evaluated as measures of the genetic impact of the sires. This was the first experience for many commercial producers with AI, and it improved the comfort level of thousands of producers and employees in the process. It also demonstrated the impact of using truly superior boars in a commercial operation. The table below comes from Production and Marketing Characteristics of U.S. Pork Producers – 2003, more commonly known as “The (Pork Industry) Structure Study – 2003” by Chris Boessen and Glenn Grimes of the University of Missouri and John Lawrence of Iowa State University. The overall percentage of pigs produced by AI in 1997 was listed at 47.4%. The authors did not compute a weighted average for 2003, but given the shift to large farms that had occurred by then, it could easily have exceeded 90% of all U.S. pigs.

Milestone No. 8 – computerized records systems. The first computerized recordkeeping system I am aware of is PigChamp, developed at the University of Minnesota. There may have been earlier ones. These systems finally allowed objective analysis of herd performance and provided information for two groups of people who have become critical for industry prosperity – the talented managers and their consulting veterinarians. Before the advent of computerized records, the practical sphere of control for a good manager was the number of animals that he/she could personally see and supervise. Ditto for veterinarians. When you can’t impact more pigs than you can see each day, it is hard to grow the business beyond a certain point. But provide accurate information and parse that information into meaningful metrics and that same talented manager or veterinarian can impact far more pigs even if they are several hundred miles away. That knowledge level does not replace good caretakers, but it does leverage their skills and provide for more breadth of input into management decisions. Computerized records and analysis provided the information that allowed skilled managers and their veterinarians to extend their reach enough to “out-compete” operations that were less well-managed and grow in economic conditions which drove others out.

Milestone No. 9 – lean value pricing. I can’t find it in my files but I believe NPPC published its first Lean Value Buying Guide in 1987 or thereabouts. As I recall, it was a matrix of percentage premiums that would be justified by various backfat thicknesses and carcass weights. It was controversial on two fronts. First, hardly any producers believed they raised bad hogs so anyone who would actually measure their hogs and pay them objectively was viewed with skepticism. Second, packers were reluctant to let producers with good hogs know they had good hogs because the producers would demand higher prices. But consumer preferences for lean products and the ultimate realization that lean hogs were substantially more efficient than fat ones finally pushed both sides to accept that sharing information was best for the business. I’m not aware of anyone accepting the NPPC guide itself, but virtually every packer began a program of paying premiums for lean hogs and discounting fat ones. The addition of electronic measuring systems drove the change even faster and the leanness of U.S. pigs began to improve quickly. It’s hard to imagine the average pig being only 48% lean, isn’t it? But that was the case before lean value pricing came along.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like