The mystery of the CME Lean Hog Index

Scenario underscores importance of USDA oversight on Livestock Mandatory Reporting.

November 14, 2022

How can a number for which the formula is public knowledge still be a mystery? That question seems to apply to the CME Lean Hog Index. There has never been any secret to the way this key economic data point is computed. CME Group, as a regulated exchange, must state clearly the terms of the contracts they offer. Since the index is used to settle all open contracts at expiration, all market participants need to know how the number is computed. There has never been any doubt on the computation yet there is some mystery about how the number changes.

The CME Lean Hog Index is a two-day weighted average of the weighted average of the average value of hogs purchased through Negotiated and Swine/Pork Market Formula (SPMF) reported each day in USDA’s “Prior Day Slaughtered Swine” report. That’s a mouthful, but it means that the index includes the number of hogs, average weight of hogs, and average price of hogs sold through those types of transactions, weighted across two successive days. It’s straightforward. Even an old guy like me can program a spreadsheet to do that every day.

And yet it is sometimes a surprise how the index changes when the spot (negotiated) hog market and cutout value move in certain ways. The reason for these surprises is the relative impacts and changes of the negotiated and swine/pork formula prices. And those changes have nothing do with CME Group and everything to do with USDA’s Livestock Mandatory Reporting (LMR) system.

USDA defines negotiated and swine/pork marketing formula prices as:

Negotiated: A cash or spot market purchase by a packer from a producer under which the base price for the livestock is determined by seller-buyer interaction and agreement on a delivery day where the livestock are scheduled for delivery not more than 14 days after the date on which the livestock are committed to the packer.

Swine/pork market formula: A purchase of swine by packer in which the pricing mechanism is a formula price based on a market for swine, pork, or a pork product, other than a future or option for swine, pork, or a pork product.

It is important to know that USDA’s Agricultural Marketing Service is not highly involved in the classification of prices into these categories – or the other three categories that are possible. USDA has historically told packers to put their data into one of the five categories and to send it in. The packers do the classifying. Those decisions, of course, are subject to periodic audits by AMS and any “pattern of violation” of the Livestock Market Reporting Act of 1999 can result in a fine. The big concern of the audits over the years has been the accuracy of the prices and quantities reported to USDA. I have never heard much discussion about price classification decisions.

The Negotiated category is pretty straightforward.

Swine/pork market formulas are relatively straightforward, too, except for the fact that the Other Purchase Agreement (OPA) category also includes formula-priced hogs. USDA, as a matter of practice, has differentiated those two categories by putting prices in the OPA category that have features that tie them to other markets (corn, for instance) or limit the range of price changes (windows, profit or margin features, etc.) or anything else different from a straight formula. OPA is a “catch-all” category.

The potential trouble is that contracts change over time and some that once were a perfect fit for the SPMF category may have had some “either/or” clause added that make it, say, a percent of cutout if the base price gets above or below a certain level. That kind of feature would normally put it into the OPA category, but there is no guarantee that I know of that such a change would be made. Remember that price classification is up to the packer. It would be very easy to not get a classification changed when a new feature is included in a contract.

I am not suggesting that packers are manipulating prices in a manner that isn’t according to Hoyle. My point is that things change and may not always get moved to the right place in a complex system. Leaving some “switching” or “window” agreement in the SPMF category would make that price shift somewhat different than one would expect when observing the negotiated hog price (which usually serves as the base for hog-based formulas) or the cutout value (which is usually the “pork” part of a swine/pork market formula). What would look logical given a specific change in the underlying values may not turn out to be true.

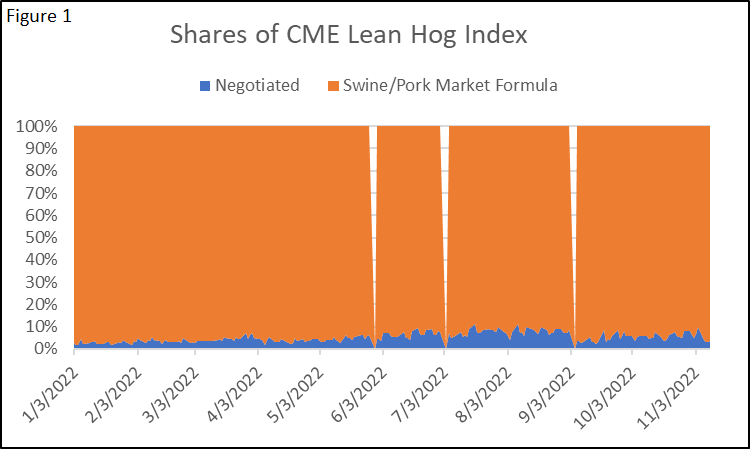

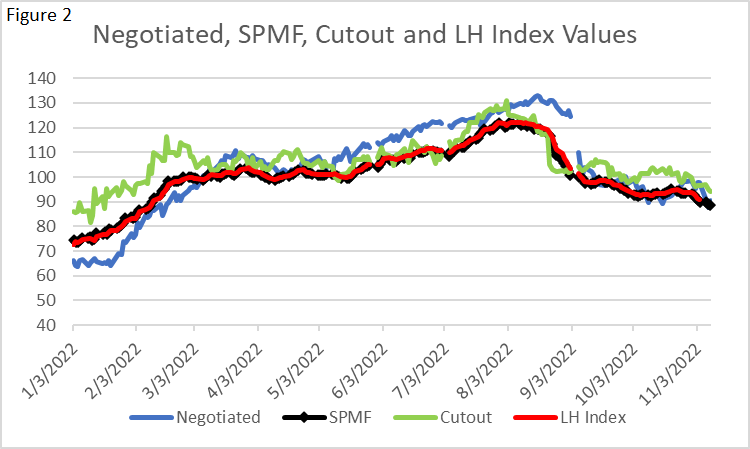

But there is good news. If you want to know where the CME LH Index may end up, you really need only look at the SPMF. It comprises such a huge portion of the index that the index follows it very closely (See Figures 1 and 2). The bad news is that you still must predict the SPMF. You can see from Figure 2, however, that it usually does not change much from day to day.

I don’t believe there is anything nefarious going on, but the scenario I have laid out underscores the importance of USDA oversight on LMR. Making sure that the prices are being classified correctly when reported by packers is important and makes other factors more understandable and, perhaps, predictable. Both would be helpful in a risky world.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like