Understanding PEDV shedding, immune response aids in implementing gilt acclimation

March 28, 2016

Porcine epidemic diarrhea virus is an economically devastating enteric disease introduced in the United States in 2013. Clinical signs in naïve herds are similar to transmissible gastroenteritis virus, including severe diarrhea and vomiting in pigs of all ages and high morality in pre-weaned pigs. PEDV is transmitted via fecal-oral contamination.

While PEDV can be eradicated out of individual breeding herds utilizing herd closure, feedback, improved sanitation and in some cases vaccine, the biggest question is how to deal with the incoming naïve gilts back into the herd. Some producers have deemed the risk of having naïve gilts back into the breeding herds as too great of a risk and have moved to acclimating gilts off site prior to entry back into the breeding herd.

The most common question surrounding this practice is to understand how long gilts are infectious after they have been exposed to PEDV as an acclimation practice. Another question is which tests are best to use in order to determine shedding and immunity. Therefore, the purpose of the study was to (1) describe shedding patterns in growing gilts; and (2) evaluate immune responses in serum and oral fluid samples.

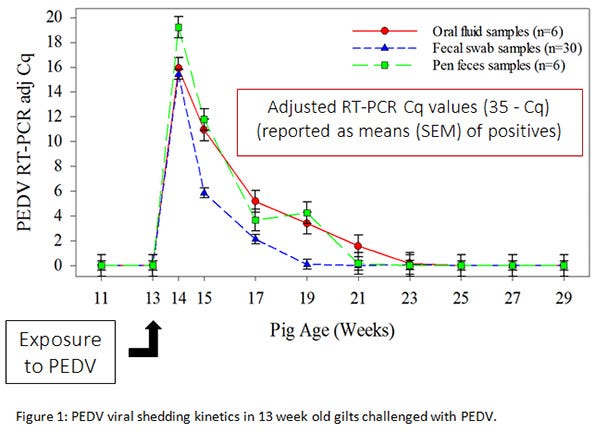

In order to answer these questions, rectal swabs (n=30), oral fluid (n=6) and pen fecal samples (n=6) were collected from two wean-to-finish gilt production sites (Farm 1-PEDV positive; Farm 2-PEDV negative). At approximately 13 weeks of age, Farm 1 pigs were exposed to PEDV using standard field exposure techniques. On Farm 1, PED virus was detected by diagnostic testing (RT-PCR) at six days post exposure in individual fecal swabs, pen fecal samples and pen oral fluids (Figure 1). Rectal swabs appeared to be positive until 42 days post-challenge. Pen fecal samples and oral fluids were intermittently positive until 56 and 70 days exposure, respectively. This study concluded PEDV diagnostic tests (RT-PCR) were effective for all sample types tested (fecal swabs, pen fecal samples, oral fluid), but the highest proportion of positive samples was observed in oral fluid samples, followed by pen feces.

This study concluded PEDV diagnostic tests (RT-PCR) were effective for all sample types tested (fecal swabs, pen fecal samples, oral fluid), but the highest proportion of positive samples was observed in oral fluid samples, followed by pen feces.

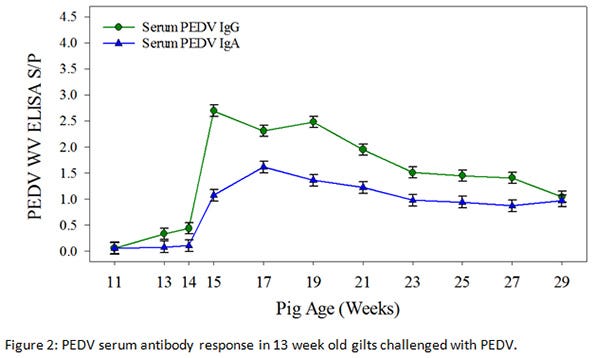

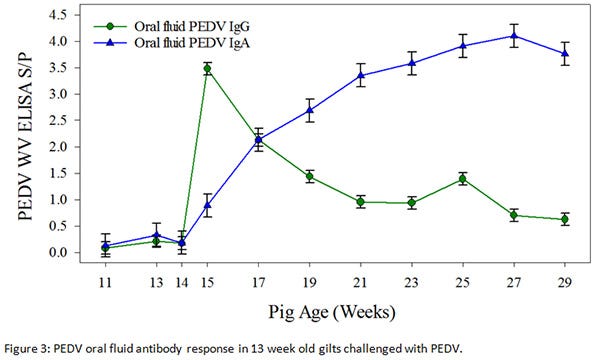

PEDV immune responses (as measured by IgG and IgA antibodies) were detected in the oral fluids and serum samples at 13 days post exposure (Figure 2 and 3). In serum, IgG appears to be the predominant antibody type to use in monitoring for PEDV exposure, whereas IgA becomes the predominant antibody type to screen for using oral fluids. The oral fluid IgA immune response increased through 97 days post exposure, while serum IgA responses peaked at 27 days post exposure.

This oral fluid IgA response is particularly noteworthy because of the level and duration of immune response. Further research would need to be conducted to determine if this oral fluid response correlates to piglet protection.

Oral fluids appear to be a fantastic sample to use to monitor PEDV in populations with either PCR or antibodies. One might consider using PCR technology when trying to decide if diarrhea is in a group of pigs currently. If a producer is trying to determine if a group of pigs or a site have been exposed to PEDV in the past, then using an IgA ELISA antibody test on an oral fluid sample would be an ideal method to answer this question. The Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Lab is currently able to run either of these assays to help producers and veterinarians answer these questions.

We would like to extend many thanks to Katie Woodard, Marisa Rotolo, Chong Wang, Pete Lasley, Jianqiang Zhang, David Baum, and Phillip Gauger for their contributions to this research.

You May Also Like