Variability of piglet birth weights balanced with sow nutrition

Traditional litter characteristics used to evaluate sow reproductive performance may not tell the complete story for modern sows. Evaluating sow feeding strategies able to promote performance of large litters demand attention.

May 16, 2019

By Jorge Y. Perez-Palencia and Crystal L. Levesque, South Dakota State University Department of Animal Science

Genetic selection and advances in reproductive technologies have increased the prolificacy of sows, allowing them to wean more than 30 pigs per year. However, the numbers of lightweight piglets have increased along with the within-litter variation of piglet birth weight. Owing to these changes, new challenges have arisen for the swine industry, within them: small piglets affected by intrauterine growth restriction, increased postnatal piglet mortality and impairment of subsequent growth performance. In this context, producers and researchers have investigated nutritional strategies to allow large litters to succeed and promote adequate performance for sows and piglets.

In this regard, it is important to examine the parameters used to evaluate the sow’s performance and their effectiveness in the current context of modern sows. For example, litter quality at parturition is based on the total number of piglets born, number of piglets born alive, total litter weight, individual piglet birth weight, and the number of stillbirths and mummified. During the lactation period, pre-wean mortality, numbers of pigs weaned, the total and individual pig weaning weight, and average daily gain are most often considered parameters. However, are these parameters sufficient to evaluate the full potential of a nutritional strategy for sows to succeed with large litters?

Uniformity is important in all stages of swine production and, due to the impact on market price, is commonly considered in the evaluation of nutritional strategies during the grow-finish phase. However, Douglas et al. (2013), using two databases (approximately 130,000 pigs) analyzed factors (i.e. birth weight, wean weight, month of birth, sex and breed) associated with poor growth performance of pigs from birth to slaughter and the capacity of piglets born small to compensate for that initial body weight deficit. According to the weight category analysis, the authors concluded that piglets with the lightest birth weight were able to exhibit compensatory growth from birth to slaughter with 74% (Database 1) and 82% (Database 2) of the pigs moving up at least one body weight category. More attention should be paid to piglets in lower weight categories because lightweight piglets are positively correlated with preweaning mortality and negatively correlated with the growth performance during suckling. However, it is likely that any significant effects on the performance of the smaller weight piglets may not be obvious when considering only the average litter weight and not the piglet variation within the litter.

Piglet performance data from three experiments performed at South Dakota State University (131 sows, 1,438 pigs) evaluating the influence of maternal phytogenic oil supplementation on piglet performance during lactation were compiled. Each trial evaluated a different commercially available phytogenic oil supplement; however, in all studies, the product was added on top of the first morning feed according to manufacturer’s recommendations beginning when the sows entered the farrowing room and continuing up to weaning. Daily animal care, lactation diet fed, targeted litter size (i.e. 13 piglets by 48 hours after birth) and wean age (20± two days) were consistent across all trials. Patterns in piglet performance by weight category and litter variation were assessed.

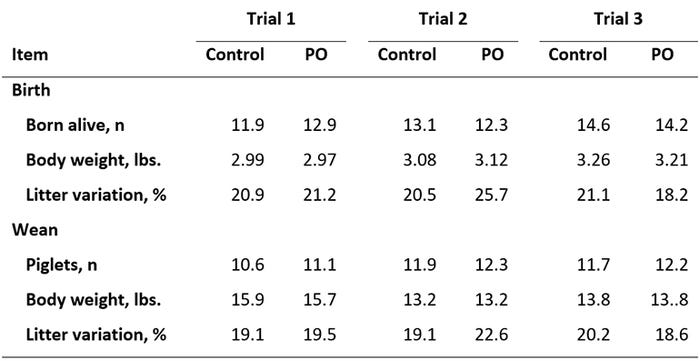

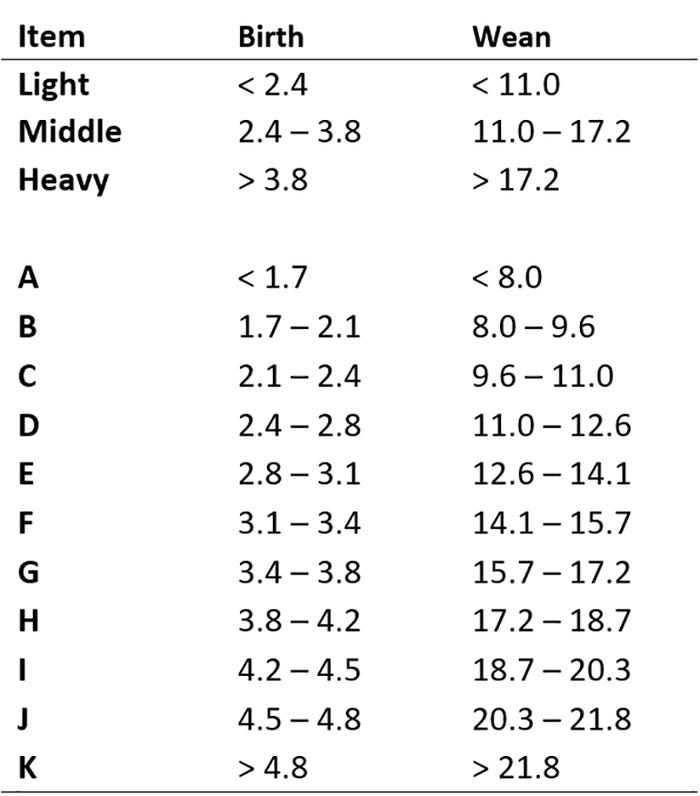

There were minor differences observed in piglets born alive per litter and average piglet birth or wean weight; however, phytogenic oil supplemented sows consistently suckled 0.5 additional piglets to weaning (Table 1). In all treatment groups but one, litter variation was lower at weaning than birth with the largest reduction in litters from supplemented sows (Trial 2). Piglets from each litter were assigned to a litter weight category designation as listed in Table 2.

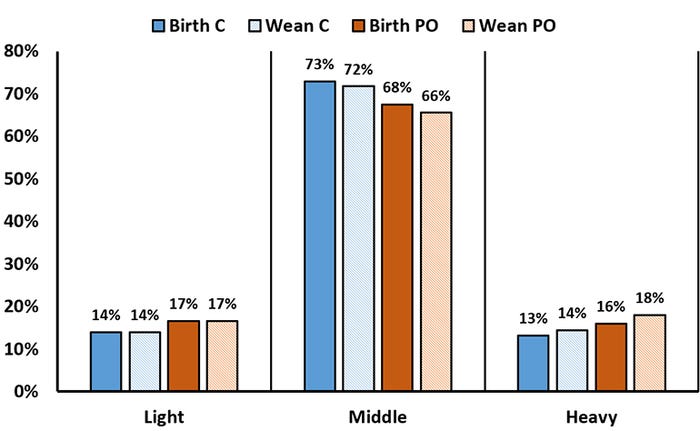

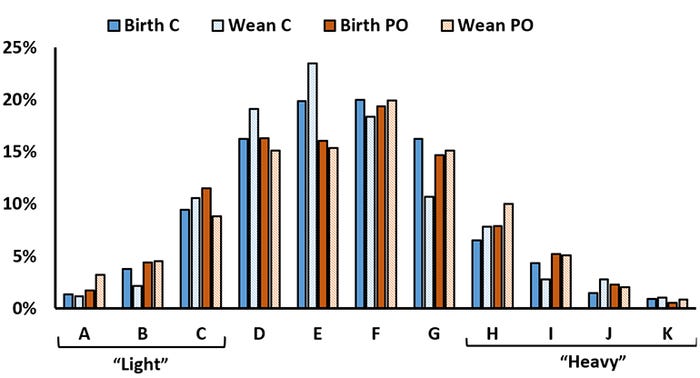

There was little change from birth to wean for either group of sows in the proportion of piglets deemed light (Figure 1). In both groups of sows, there was movement of middle-weight pigs into the heavy-weight category, with slightly more pigs in the heavy category at weaning from phytogenic oil-supplemented sows. To better assess which piglets within the middle category were likely exhibiting compensatory growth, piglets were separated into 11 categories (Table 2) at birth and weaning. Based on Chi-squared analysis (P = 0.035), a greater proportion of piglets in control litters fell back into the lower end of “middle” and upper of end of “light” weight categories. Similar to birth weight, pigs at the lower end of “middle” (i.e. ≤13 pounds) and “light” are more likely to continue to fall back or require additional care after weaning (i.e. veterinary treatment).

The traditional litter characteristics used to evaluate sow reproductive performance may not tell the complete story for modern sows. Therefore, evaluating sow feeding strategies that are able to promote the growth performance of large litters demand special attention. Indeed, a simple average may not be, by itself, an adequate index to assess impact of sow nutrition on piglet performance. New evaluation techniques will be increasingly needed to better explore the potential of nutritional strategies and to track progress in productive characteristics of pigs.

References

Douglas, S. L; S. A. Edwards; E. Sutcliffe; P. W. Knap; I. Kyriazakis. 2013. Identification of risk factors associated with poor lifetime growth performance in pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 2013.91:4123–4132 doi:10.2527/jas2012-5915

Sources: Jorge Y. Perez-Palencia and Crystal L. Levesque, who are solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly own the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset.

You May Also Like