Coping with shortage of vitamins A and E in swine diets

Current recommendations for vitamins A and E are outdated, but nutritionists, veterinarians and meat scientists should take an integrated approach to determine steps in the pork production system to help cope with the current short supply of these vitamins.

January 18, 2018

By Jae Cheol Jang, Lee J. Johnston, Gerald C. Shurson and Pedro E. Urriola, University of Minnesota Department of Animal Science

Prices of vitamins A and E have risen recently and in some cases supply is restricted. In this column, we present a system-wide approach to cope with limited access to these vitamins.

Essential use and requirements

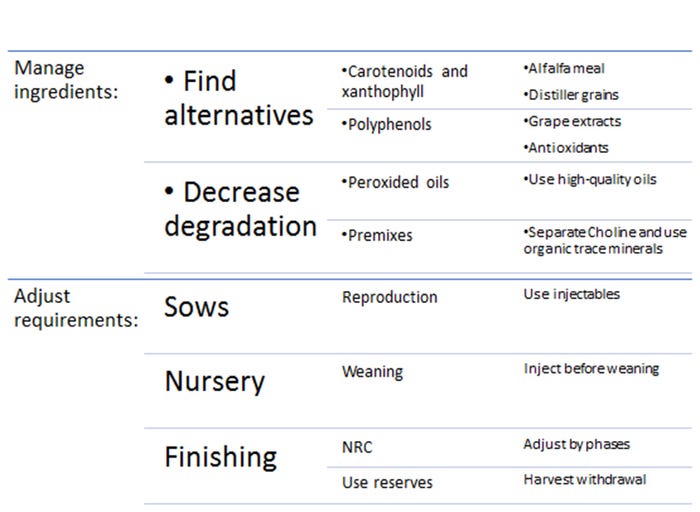

Vitamins are essential for numerous metabolic functions in pigs and must be supplemented. The majority of nutritionists add four times more vitamin A and E than recommended by the National Research Council1,2. These high safety margins are a result of uncertainty and variability of vitamin requirements as well as being a relatively small component (<1%) of total diet cost3. However, there are strategies that can be used to minimize the risk of vitamin A and E deficiencies during this period of short supply (Figure1).

Figure 1: System-wide approach to shortage of vitamins A and E

Premix and diet formulation

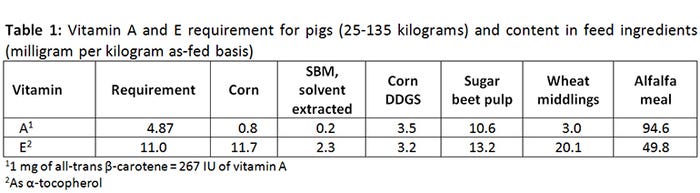

The first approach is to minimize safety margins when formulating premixes. Assuming that diets have been well fortified with vitamin A and E in diets previously fed, rely on stored body reserves of these vitamins to make up any potential deficiencies that may occur when feeding diets at the requirement levels. Another approach is to formulate diets with feed ingredients that contain high concentration of vitamins A and E (Table 1). For example, a corn-soybean meal based diet contains 0.6 milligrams per kilogram vitamin A which covers 12.3% of the requirement, while a corn-SBM-corn DDGS based diet contains 1.41 milligrams per kilogram vitamin A which covers 29% of the requirement.

Studies4-11 suggest that removing vitamin and trace mineral premix 35 to 42 days before slaughter may not affect growth performance of finishing pigs. Consequently, removing vitamins A and E from “least risk” population appears to be viable way to spare vitamin A and E for use in diets for “greater risk” population (i.e., younger pigs and sows).

Minimize degradation throughout the supply chain

Vitamins lose biological activity when exposed to high temperatures, humidity, oxygen, pro-oxidants (i.e. copper, iron, zinc, choline chloride) and light during storage. Consequently, minimizing storage time of premixes and exposure to these pro-oxidant conditions before mixing in complete feeds will minimize the need for high safety margins12. Likewise, choline and inorganic trace minerals accelerate the rate of loss of vitamin potency during storage. Formulating and storing vitamins, trace mineral and choline chloride premixes separately, or using organic trace minerals13 will minimize the rate of vitamin potency losses.

Minimize oxidative stress

Feeding diets with peroxidized fats and oils can decrease (50%) serum and liver concentrations of vitamin E14. Likewise, avoiding low-quality oils or feed ingredients that decrease lipid absorption (e.g. alginate, pectins) decreases metabolic requirements of vitamin E. Feeding ingredients (e.g. DDGS) that contain sufficient antioxidant compounds (e.g. ferulic acid and xanthophylls) may mitigate the impact of lipid peroxidation15.

Alternatives to vitamin A and E

Polyphenols have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties making them alternatives to vitamin E16. Carotenoids are converted to retinol(al) and may cover a portion of the requirements for vitamin A, but conversion efficiency (average 40:1) varies depending on multiple factors17. There are commercial carotenoid or polyphenol products (e.g., AOX from Provimi) that have variable capacity to replace vitamins A and E.

Strategically use injectable forms

Weaned pigs are likely to be most vulnerable to inadequate vitamin A and E status, and using injectable products at the time of weaning may be warranted when feeding starter diets without excess concentrations of these vitamins.

What should you watch for?

The major disorders of vitamin A deficiency are neurological and reproductive, while vitamin E deficiency is associated to diseases like Mulberry Heart Disease. Veterinary diagnostic laboratories may assist with diagnostic evaluations.

Finally, inclusion of vitamin E in finishing pig diets at levels greater than NRC requirements may increase shelf stability of pork. Therefore, it is necessary to monitor products destined to export18.

In conclusion, current recommendations for vitamins A and E are outdated, but nutritionists, veterinarians and meat scientists alike should take an integrated approach to determine steps in the pork production system to help cope with the current short supply of these vitamins.

References

1 National Research Council. 2012. Nutrient Requirements of Swine. 11th Rev. Ed. National Academy Press, Washington, D.C.

2 Dritz, S. S., J. R. Flohr, J. M. Derouchey, J. C. Woodworth, M. D. Tokach, and R. D. Goodband. 2016. A survey of current feeding regimens for vitamins and trace minerals in the US swine industry. J. Swine Heal. Prod. 24:290-303.

3 Kim, B. G., and M. D. Lindemann. 2007. An Overview of Mineral and Vitamin Requirements of Swine in the National Research Council (1944 to 1998) Publications. Prof. Anim. Sci. 23:584-596.

4 Patience, J. F., and D. Gillis. 1996. Impact of preslaughter withdrawal of vitamin and trace mineral supplements on pig performance and meat quality. Pages 29-32 in Monograph No. 96-01. Prairie Swine Centre Inc., Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, Canada.

5 Mavromichalis, I., J. D. Hancock, I. H. Kim, B. W. Senne, D. H. Kropf, G. A. Kennedy, R. H. Hines, and K. C. Behnke. 1999. Effects of omitting vitamin and trace mineral premixes and (or) reducing inorganic phosphorus additions on growth performance, carcass characteristics, and muscle quality in finishing pigs. J. Anim.Sci. 77:2700-2708.

6 McGlone, J. J. 2000. Deletion of supplemental minerals and vitamins during the late finishing period does not affect pig weight gain and feed intake. J. Anim. Sci. 78:2797-2800.

7 Edmonds, M. S., and B. E. Arentson. 2001. Effect of supplemental vitamins and trace minerals on performance and carcass quality in finishing pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 79:141-147.

8 Shaw, D. T., D. W. Rozeboom, G. M. Hill, A. M. Booren, and J. E. Link. 2002. Impact of vitamin and mineral supplement withdrawal and wheat middling inclusion on finishing pig growth performance, fecal mineral concentration, carcass characteristics, and the nutrient content and oxidative stability of pork. J. Anim. Sci. 80:2920-2930.

9 Ayuso, M., A. Fernández, B. Isabel, A. Rey, R. Benítez, A. Daza, C. J. López-Bote, and C. Óvilo. 2015a. Long term vitamin A restriction improves meat quality parameters and modifies gene expression in Iberian pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 93:2730-2744.

10 Ayuso, M., C. Óvilo, A. Rodríguez-Bertos, A. I. Rey, A. Daza, A. Fernández, A. González-Bulnes, C. J. López-Bote, and B. Isabel. 2015b. Dietary vitamin A restriction affects adipocyte differentiation and fatty acid composition of intramuscular fat in Iberian pigs. Meat Sci. 108:9-16.

11 Henriquez-Rodriguez, E., R. N. Pena, A. R. Seradj, L. Fraile, P. Christou, M. Tor, and J. Estany. 2017. Carotenoid intake and SCD genotype exert complementary effects over fat content and fatty acid composition in Duroc pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 95:2547-2557.

12 DSM. 2018. Vitamin Stability.

13 Shurson, Gerald C., Troy M. Salzer, Dean D. Koehler, and Mark H. Whitney. 2011. Effect of metal specific amino acid complexes and inorganic trace minerals on vitamin stability in premixes. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 163: 200-206.

14 Hung, Y. T., A. R. Hanson, G. C. Shurson, and P. E. Urriola. 2017. Peroxidized lipids reduce growth performance of poultry and swine : A meta-analysis. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 231:47-58.

15 Song, R., and G. C. Shurson. 2013. Evaluation of lipid peroxidation level in corn dried distillers grains with solubles. J. Anim. Sci. 91:4383-4388.

16 Brenes, A., A. Viveros, S. Chamorro, and I. Arija. 2016. Use of polyphenol-rich grape by-products in monogastric nutrition. A review.” Anim. Feed Sci. and Technol. 211:1-17.

17 Green, A. S., and A. J. Fascetti. 2016. Meeting the Vitamin A Requirement: The Efficacy and Importance of β -Carotene in Animal Species. Sci. World J. doi:10.1155/2016/7393620.

18 Boler, Dustin Dee, S. R. Gabriel, H. Yang, R. Balsbaugh, D. C. Mahan, M. S. Brewer, F. K. McKeith, and J. Killefer. “Effect of different dietary levels of natural-source vitamin E in grow-finish pigs on pork quality and shelf life.” Meat science 83, no. 4 (2009): 723-730.

You May Also Like