Industry volatility demands readiness to capitalize on price swings in commodity inputs and markets. Risk management is a moving target in these volatile times

January 18, 2011

Risk management is a moving target in these volatile times, says 25-year veteran strategist Joe

Kerns of International Agribusiness Group, based in Ames, IA.

“An analogy I provided to participants at Kansas State Swine Day this November was, ‘In these times, making the proper marketing decisions is like having an ax swinging over your head — as long as you duck at the proper times, you will be okay.’

“The problem is if you are going to try to do this without a helmet of some sort; eventually it is going to become fatal. I truly am afraid that is what is going to happen,” he warns.

The commodity markets for grains and livestock run on averages, but there are also numerous peaks and dips along the way. When the market aberrations turn in their favor, that’s when producers need to learn to take action, says Kerns, who for 14 years was in charge of feed acquisition for Iowa Select Farms at Iowa Falls.

Pricing Opportunities

Options and futures markets are good tools, but many times the best opportunities are in the cash market, he says.

In a recent example, Kerns was able to help a client in southwest Minnesota purchase new crop corn at $4.15/bu. at the elevator (Dec. 11 futures market). “By doing so, this producer has locked in a relatively wide basis between existing futures and cash prices at a value that provides good risk management. Basis is simply defined as the difference between cash and futures prices,” he explains.

Market aberrations are also seen on the hog revenue side. October hogs were trading at $80/cwt., carcass. “We have virtually never traded October hogs at $80; for about two days, they were there on the futures market,” he recalls.

Producer Paradox

Pork producers face somewhat of a commodity paradox. Intrinsically, they are always “short” of supply on grains and “long” on supply of hogs. The law of economics suggests that most times, producers don’t get the opportunity to take advantage of the best of both worlds — buy $2.50/bu. corn and sell $90/cwt. hogs, for example.

“But the law of economics does allow these types of things to occur for very short periods of time. So you’ve got to stay vigilant because there are disruptions in the market that you must be ready to act on,” Kerns emphasizes.

As another example, October 2011 soybean meal is trading at a $30/ton discount. “From January to at least July and into August, soybean meal was trading for around $330/ton, and the October contract drops down to $300/ton,” he says. This turn of events provides a potential opportunity considering the 2011 soybean crop isn’t even close to being in the ground, the variability of the growing season in recent years, and the fact that it is unlikely that soybean demand will drop next year. Those are all factors that seem to point to higher soybean prices.

“So, if my producer in southwest Minnesota buys new crop corn at this attractive price and combines it with this discount on soybean meal, then going into February 2012 marketings, he is actually going to show a profit on hogs,” Kerns notes.

On the input side, producers must work to reduce their risk by reducing their cost of production.

Producers can occasionally buy risk protection against price swings in the futures market for pennies on the dollar, he adds.

Status Quo Won’t Work

Pork producers often say they have no position in the commodity markets, but Kerns says their inaction is a position in itself. Not taking advantage of sudden market swings can essentially increase the cost of inputs or reduce potential revenues.

“If you do nothing, you have chosen a position that is short corn and intrinsically long hogs,” he reinforces.

Working with reluctant producers, the first objective Kerns has is to get them to at least recognize that doing nothing is a risk position. Once they recognize that, then they can be advised on the models and tools available to change their fortunes.

Kerns says producers need to use the publicly available government reports and specialized tools (industry influencers, stakeholders, bankers, fund managers, other producers, etc.) to develop a strategy, and then properly execute it when the right pricing opportunities present themselves.

Currently, if producers haven’t formulated a risk management plan, they are probably losing money in the hog business, which means they face the difficult prospect of convincing their banker to lend them more operating capital in 2011.

A good place to start is managing cost of production from the standpoint of production practices, supplier contracts, procurement programs and dietary regimens.

If you raise hogs and crops, always view and balance both sides of the commodity equation. “You should look at your production enterprise, not as a consumer of corn and producer of hogs, but as a very dynamic, interrelated, opportunistic situation,” Kerns says. Realize that corn prices have been escalating over the last several years, and along with that uptick in the trend line, there has been a corresponding change in breakeven prices for hogs (Figure 1).

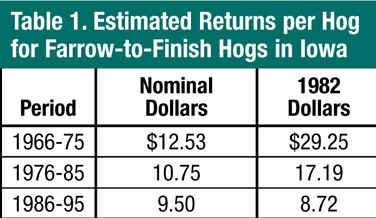

These events arose from decades of cheap grain that spurred an influx of Wall Street money to build corporate-type hog farms as financial analysts saw an industry that was too profitable, too long to be ignored (Table 1). However, many of the large systems were built on hogs, ignoring the need for a grain base to support the hog enterprise, Kerns says.

Adding insult to injury, there has not been an immediate correlation between the grain and the hog market revenue side. Kerns points out that when corn prices rise, say to $7/bu., look for hog prices to eventually rise, possibly reaching $90/cwt., carcass weight. “These things are going to move in lockstep with one another in the future,” he assures.

Future Looks Bright

A number of economic pundits don’t paint a very rosy future for hog producers in 2011-2012, what with rising costs on the input side. But Kerns feels if producers correctly pick their battles, many will survive.

“The input side is where everything has got to start. Those who are still viable in this industry have gotten there because they are pretty doggone good producers. The sad part is that the difference between producing 22 and 28 pigs/sow/year (p/s/y) isn’t going to be the defining factor between the winners and the losers in the future. If you’ve done nothing to protect yourself when there are positive returns on the board, then all that means is if you’re producing 28 p/s/y, then you’re losing more money than the guy at 22 p/s/y when times get tough,” he says.

The danger, of course, is that not enough producers will take advantage of these market aberrations, sending the pork industry spiraling into further shrinkage.

Producers in the best position to survive are those with adequate grain supplies to coexist with their hog operations, and who retain the option of choosing to sell part of their grain or feed it to their hogs.

Choosing to run the grain business at a breakeven margin in order to feed the livestock operation is so much more competitive than other alternatives, thus ensuring those producers’ survival, provided financing can be acquired, Kerns states.

Acquiring financial capital means assembling a plan that articulates your ability to put together cash flows and hedging strategies that protect not only your interests but your lender’s interests as well, he stresses.

To contact Kerns, call (800) 334-8881, extension 224. In Iowa, call (515) 689-0522.

You May Also Like