COVID-19 causing hog slaughter to plummet

Declining hog slaughter causes a shortage of pork which should push up retail pork prices. We began 2020 expecting a record supply of red meat and poultry.

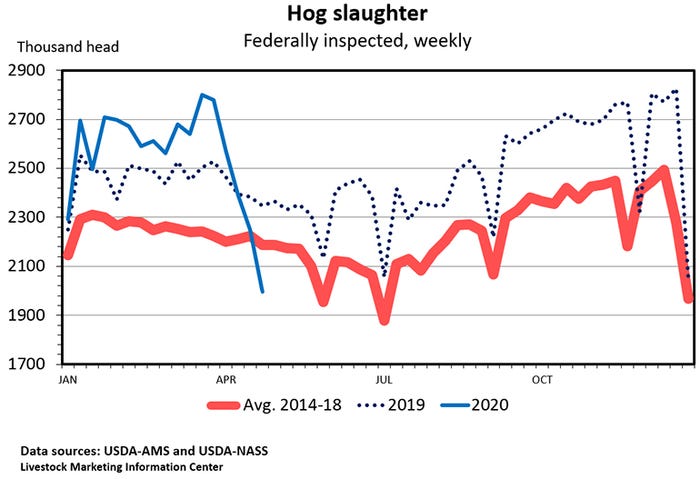

The coronavirus epidemic is the driving force for many things these days, including hog and pork markets. COVID-19 has forced several hog slaughter plants to temporarily close — Tyson: Columbus Junction, Waterloo, Logansport; Smithfield: Sioux Falls, Monmouth; JBS: Worthington; Indiana Packers: Delphi. Other plants have had to slow their operations because of worker illness. As a result, daily hog slaughter has dropped dramatically in the last 30 days.

Hog slaughter exceeded 500,000 on four different days in March. This past week, the biggest daily kill was just 365,000 head. Last week's hog slaughter totaled 1.995 million head. That was down 11.3% from the week before, down 15.0% from the same week last year, and the lowest slaughter for a non-holiday week since August 2014.

This drop in slaughter is not due to a shortage of market hogs. USDA's March Hogs and Pigs report indicated hog slaughter during the last three weeks would be up 3.9% compared to last year, but it was actually down a whopping 6.8%.

Slaughter the week ending April 11 was 93,100 below expected;

slaughter the week ending April 18 was 228,100 below expected;

slaughter the week ending April 25 was 442,600 below expected.

It's not that packers don't want to slaughter more hogs. Because of COVID-19, they couldn't.

Slaughter capacity, if all were ideal, is roughly 2.8 million hogs per week. Based on the March market hog inventory, expected slaughter during the last three weeks was roughly 2.47 million per week. That would have been 330,000 head per week below ideal-condition capacity. If these numbers are right, it may require nearly three weeks with slaughter at capacity to cover the shortfall of the last three weeks.

If, as expected, coronavirus continues to spread among packing plant workers and hog slaughter remains severely depressed, it may be months before slaughter catches up with desired marketings. In the meantime, packers will face more hogs than they can handle, and producers will struggle to find a home for their hogs.

Hog slaughter weights started 2020 above the year-ago level and have been declining slowly. This indicates that hog marketings were likely current in early April at the start of the COVID-19 driven decline in hog slaughter.

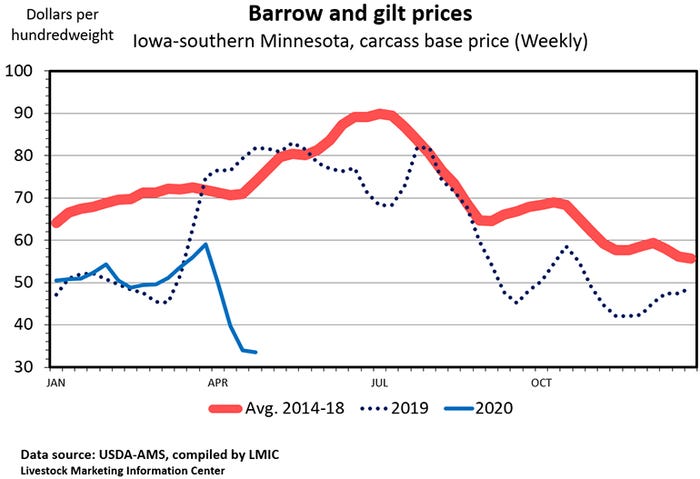

April hog prices were too low for producers to survive for long. Despite the big drop in slaughter, current hog prices are higher than I might expect. The COVID-19 driven shortfall in slaughter is causing hogs to back up on farms and is driving down hog prices. The last time slaughter capacity was seriously below desired marketings for a prolonged period was in November-December 1998.

At that time, cash hog prices dropped as low as $10 per hundredweight. What will keep hog prices above $10 per hundredweight in the coming days? Hopefully, packers will be able to restore plant operations soon. Producers' ability to maintain an increasing number of hogs on farms and thereby avoid a marketing panic. Perhaps, packers' reluctance to see producers go out of business? Once processing plant workers are again free of the coronavirus, packers will need a lot of hogs to feed their plants.

Most producers price hogs on a formula, often tied to the cutout value or the futures market. Only a small percent of hog packer purchases is negotiated. When desired marketings exceed slaughter capacity, the negotiated hog price can approach zero. Processing is an essential part of the marketing chain. Few housewives will except a live hog as substitute for sliced bacon.

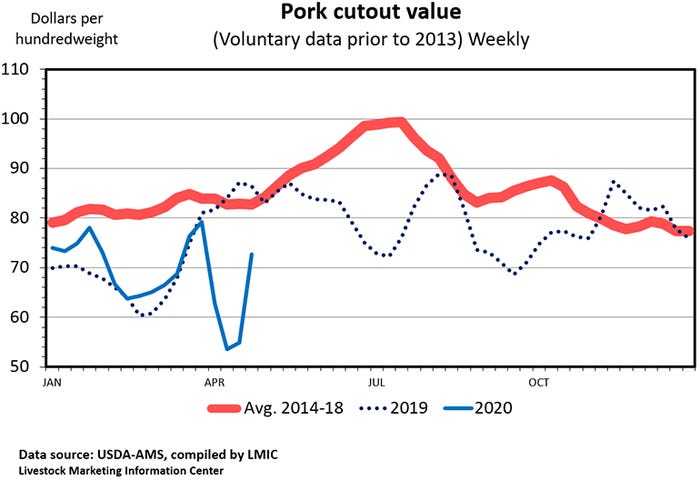

When hog slaughter goes down, pork production goes down and cutout value usually increases. Last week's pork production was 428.6 million pounds, down 15.0% from a year ago. Last week's pork cutout value averaged $72.69 per hundredweight, up 32.6% from the week before, but down 15.8% from the same week last year.

Pork cutout value has been erratic lately. Despite increased pork production, the cutout value started the year a bit above last year thanks to strong exports. The cutout value dropped dramatically in late-March before rebounding in recent days. If COVID-19 keeps packing plant workers at home and thus keeps hog slaughter and pork production low, then wholesale pork prices should rise. However, if further processing (trimming, curing, packaging) is constrained by worker illness, then the rise in wholesale value will be constrained.

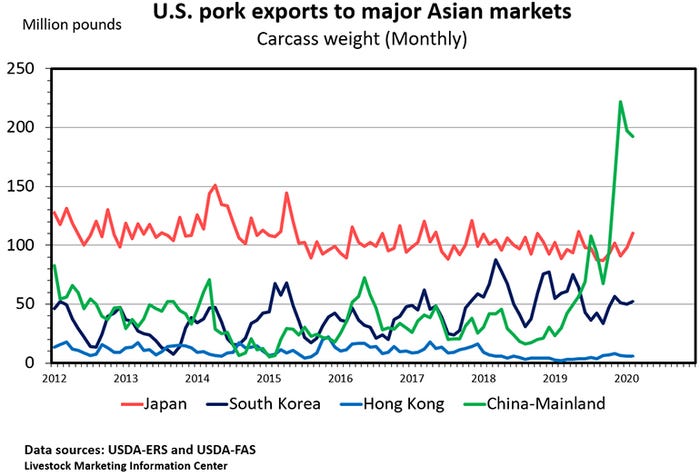

International trade has been kind to the pork market in recent months. Pork imports have been below the year-ago level for each of the last 22 months. Pork exports have been above the year-ago level for the last nine months and up by double digit percentages in the last four months.

Another disease, African swine fever, has boosted U.S. exports to China, the world's largest pork consumer. Since November, China has been the biggest foreign buyer of U.S. pork. Shipments to China in February totaled 192.46 million pounds, more than six times what was shipped a year ago and 39% more than shipments to Mexico, our No. 2 foreign buyer. In February, 28.5% of U.S. pork production was exported with 8.3% of production going to China.

Declining hog slaughter causes a shortage of pork which should push up retail pork prices. We began 2020 expecting a record supply of red meat and poultry. This year's slaughter of hogs, cattle and poultry each is expected to be above last year. Thus, one would expect consumers would find lots of meat in stores. But, if too many processing plants are idled because of COVID-19, meat counters may be only partially filled and retail prices high.

Source: Ron Plain, who is solely responsible for the information provided, and wholly owns the information. Informa Business Media and all its subsidiaries are not responsible for any of the content contained in this information asset. The opinions of this writer are not necessarily those of Farm Progress/Informa.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like