Don’t become fatigued to PEDV

Hog farmers are encouraged to fine-tune the farm’s biosecurity action plan

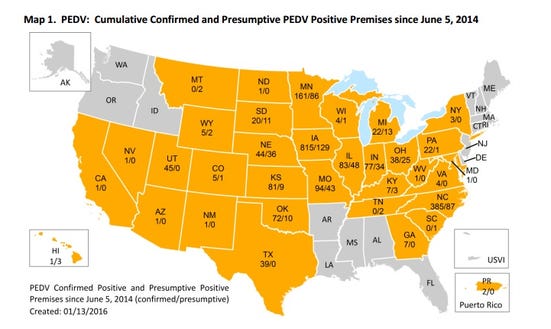

As North Dakota logs its first case of porcine epidemic diarrhea virus this winter, it is a good reminder that hog farmers need to stay on guard against the deadly virus that has killed estimated 9 million pigs since 2013. “We are not over PEDV. It is still out there and there are still farms breaking,” warns Paul Sundberg, DVM, Swine Health Information Center director. “The question that we all face is what we can do about it and how can we affect how many break.”

He adds, “There is risk of people coming fatigued from PEDV. They have heard about it so often. They may have gone through it and the assumption is if you’ve gone through it then ‘ok now I have it, now let’s get on with life’, but that is not the case.”

Fighting PEDV takes an all-embracing approach, especially with multiple ways pigs can become infected. “Unfortunately, there is no one thing people can do and say we have it taken care of. This is a comprehensive approach. It has got to be an issue of paying attention to the biosecurity details and pig management all the time,” Sundberg stresses.

Conventional wisdom tells us that there could be a higher number of susceptible animals this winter than immediately following the 2013 outbreak, Sundberg says. It is something that puts the hog industry at higher risk for PEDV outbreak, moving into 2016. One loud and clear message for all producers and veterinarians is biosecurity is imperative. Hog farmers and the entire industry need to continuously focus on keeping PEDV at a low-level as seen in the spring of 2014 when the infections started to go down.

Typically, the winter months trigger the largest attention for protecting the farm from PEDV outbreak. However, the recent battle with the virus showed that cold temperatures was not the only time the virus can hit, given its highly contagious nature. In many parts of the United States, El Nino has fostered unusual weather patterns and above-normal temperatures in the last month of 2015.

Derald Holtkamp, DVM, Iowa State University, says so far PEDV activity has been relatively low, likely a result of a combination of things: strong focus on biosecurity, herd immunity and vaccination program.

While Holtkamp says it is human nature to get complacent, thus far it does seem a little different with a sustained determination by producers to remain vigilant. Based on outbreak investigations completed by Holtkamp’s team, he says “People have really upped their game, especially the large production systems when it comes to biosecurity. They raised the bar.”

Recognize biosecurity gaps

Still, hog farmers are encouraged to fine-tune the farm’s biosecurity action plan by working with veterinarians and other third-party professionals to identify gaps and tailor it their biosecurity protocols to the farm’s individual situation.

Holtkamp says it is important to understand the farm’s biosecurity gaps. He stresses there is not a one-size-fits-all biosecurity plan. Architecting an effective plan starts with a complete assessment of all events that occur on the farm on a regular basis – such as entry of semen, removal of wean pigs, introduction of gilts and entry of employees. Producers may consider a third-party assessment, like one offered by Holtkamp’s team at ISU, since simple things can provide big risk for introduction of pathogens.

He cautions veterinarians and hog producers to not assume previous problems are resolved. For instances, he says almost every sow farm has showers installed in the barns and a shower-in and shower-out policy. However, how the showers are used can leave a farm exposed. Towels can be passed back and forth and people sometimes pass through without showering. It really is a blind area and something you cannot closely monitor. Holtkamp urges producers to add layers of protection. The shower being present is good but adding a bench in the entryway that requires people to sit down, take their shoes off and prevents them from putting their sock foot back down where they just walked by swinging their leg over the bench into the clean area. Sometimes it is the simple inexpensive things that are often overlooked, Holtkamp notes.

It is essential to acknowledge that PEDV is a community disease, easily spread from one neighbor to another. Holtkamp says what you do affects your neighbor and what your neighbor does affects you. So, it is important producers not only improve their biosecurity but nudge their neighbors to also close gaps. “As long as their neighbors are business-as-usual, that continues to put them and the whole industry at risk,” Holtkamp says.

Holtkamp warns that while the majority of hog farmers have stepped up their game, it is not true for everyone. There are still some producers who do not see the urgency to exercise tight biosecurity, continue to raise pigs as they have always done and they have not changed their opinion on the importance of biosecurity.

PEDV outbreaks do not just happen on sow farms. The virus is found to be infecting grow-to-finishing farms. While a growing pig can become infected by different methods, one thing intense research has shown is PEDV can transfer from the processing plant. “If a finishing floor breaks after pigs are starting to be taken to the packing plant and there is traffic back and forth between the finishing floor and the packing plant, the most probable source is the packing plant. That is a biosecurity issue,” Sundberg says.

As revealed in slaughter plant research funded by the National Pork Board, trucks are an excellent vessel for carrying pathogens. In the middle of June 2013, 17% of trucks arrived positive, and 11% of the trucks that entered the premises negative left positive.

Another key transmitter of the virus is people. Evaluating the flow of people entering and leaving a farm is also crucial to a biosecurity action plan. The slaughter plant study results also showed a truck would be 4.15 times more likely to be PEDV-contaminated if a plant employee enters the truck. Given the highly contagious nature of PEDV, all individuals on the farm must be part of the defense strategy.

While transportation vehicles and people impose a risk, so do the actual feed ingredients. Pipestone Applied Research team led by Scott Dee confirmed in 2014 that PEDV can be transmitted by contaminated feed. The results of the research changed the way feed was handled by the feed mill and hog farmer. To prevent the viral entry the hog farmer is encouraged to work with the feed mill.

The NPB recommends assuming their risk with every contact. A line of separation with clear designated lines between the areas used by transporter and farm personnel needs to be created. Biosecure cleaning protocol also needs to be established for all equipment, facilities and vehicles; starting with identifying the traffic flow. The line of separation and biosecure cleaning protocol needs to be clearly communicated with all parties prior to entering the farm. For more tips visit the NPB PEDV resources materials website.

Building herd immunity

Immunity within U.S. pig herds can vary. Sundberg says, “We know that the immunity that is developed from PEDV infection in sows, for example, is not as long lasting as TGE, which is another coronavirus. According to research funded by the National Pork Board, that immunity will last a period of months rather than a period of years.”

Holtkamp says only time and more research can put an exact time frame on how long herd immunity lasts. He agrees with Sundberg that at this point it appears to be months rather than years. Long-term herd immunity is harder to achieve because of the higher turnover of sows and challenges with acclimating gilts.

Vaccinations and natural exposures are both methods use on hog farms today to help build immunity.

“Vaccination is a tool along with biosecurity and sanitation to help improve performance on the farm,” says Rick Swalla, senior veterinarian Pork Technical Services, Zoetis. “Vaccination works in both exposed and naïve herds to help build immunity and shorten the duration of these outbreaks. It is a great way to prolong immunity and maximize the contamination of a live virus at the same time.”

Holtkamp says based on his experience, producers are using vaccines in herds that have had some type of live virus exposure. For the most part, vaccines are given pre-farrow to boost immunity.

Some herds are using natural exposure with gilts by feeding saved feedback material from initial outbreaks. Still, Sundberg says it really comes down to farm-specific procedures and consulting a veterinarian. Using natural exposure can pose a risk and so it is important to fully evaluate considering all the risks before implementing any management practices.

Holtkamp agrees there is a risk to this method. Some hog producers are reluctant to use live virus and they are choosing not to acclimate gilts. So as the herd turns over it becomes increasingly naïve to the virus and a larger target.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like