To have an effective vaccination program, it is essential for employees to understand how important their role is to the program and why vaccination is critical.

Healthy pigs equal happy pigs, excellent productivity and strong profits. As hog farmers, investing time, money and effort on management practices and strategies to keep the herd healthy by controlling harmful pathogens from spreading in pig populations yields many benefits.

Protecting the herd from harmful pathogens involves multi-layering practices to enhance immunity and prevent the infection of swine herds.

And one essential part of a swine herd health management plan is routine vaccinations. Research has shown that it is far more costly to treat an infectious disease outbreak than preventing it with a vaccine.

Before a product can be used in barns, USDA-licensed vaccines must pass rigid testing for efficacy, safety, potency and purity with the USDA’s Center for Veterinary Biologics. The long, complex process from vaccine discovery to a product used in everyday hog production ensures the vaccine will perform according to the claim for which it was labeled and its intended purpose.

Vaccines are an investment, and as hog farmers, you want them to work effectively. But there are times when hog producers and veterinarians sense a vaccine is not working. For those times, it is fair to ask the question, “Did the vaccine fail or did I fail the vaccine?”

Calling in the V-Team

Veterinarians from leading animal health companies offer some answers and practical guidance. They are:

■ John Waddell, senior professional services veterinarian at Boehringer Ingelheim

■ Reid Philips, senior technical manager at Boehringer Ingelheim

■ Thomas Painter, senior veterinarian on the Zoetis pork technical services team

What exactly defines a vaccine success or failure? As written by Kent Schwartz, DVM, Iowa State University Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory, in a previous National Hog Farmer article: “A vaccine failure implies the actual vaccine itself is somehow deficient and unable to stimulate protective immunity.”

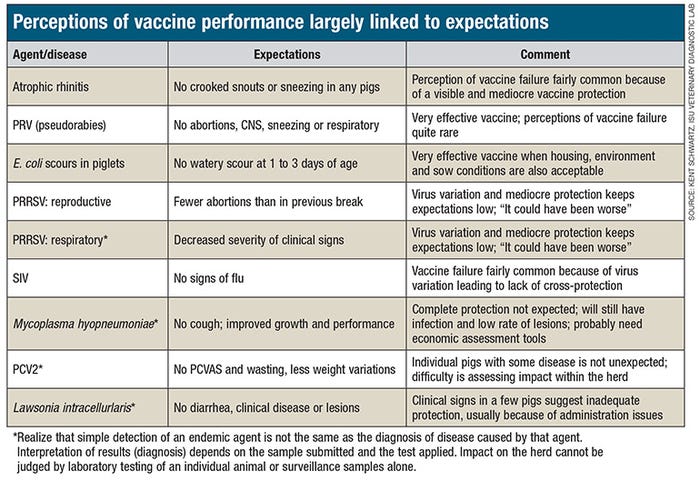

As Schwartz explains, the perception of vaccine performance is largely linked to expectations. In the table on the next page, he presents a good reference of expectations of vaccine performance by disease that Waddell and Philips find useful to assist hog producers in managing expectations.

At the barn level, a perceived failure lies with the hog producer’s expectations of the vaccine. Waddell and Philips stress that not all vaccines are perfect, but are designed to help protect pigs from the consequences of exposure to a pathogen and mitigate the impact of the challenge from the infectious agents.

“Managing expectations for a vaccine is important,” Philips says. “Vaccines may not prevent infection, but when appropriately administered, they will significantly mitigate or reduce the consequences of infection from a specific pathogen — significantly reducing the clinical signs and biologic impact of disease, and consequently improving health and performance.”

Painter notes, “I think the expectation of producers is that a vaccine will provide 100% protection, whereas the expectation of the veterinarian takes into account the limitations of a vaccine.”

Therefore, it is important to form realistic expectations. Vaccinations are not envisioned to eliminate infections from the herd but are expected to decrease the severity of clinical disease and mitigate associated performance losses. And Waddell, Painter and Philips note vaccine performance varies by disease, as do expectations. Vaccines are a single tool and should be employed as part of wider herd health protocol.

It is Waddell, Philips and Painter’s job along with other veterinarians to help educate hog farmers on what is an accurate expectation for vaccine performance for a certain disease and stage of production.

So, when an unexpected outcome happens, it is essential to take a 360-degree view in an attempt to understand the issue. A good starting point is discussing the observation with your herd veterinarian and then reporting it to the vaccine manufacturers. “If there is something wrong, we want to be the first to know,” Waddell says.

At that point, it kicks in a team to examine the “why” a vaccine failed. And if the exploration is done right, it starts to resemble a crime scene investigation.

Animal health companies take unexpected outcomes seriously. It is a priority for technical veterinarians like Waddell, Philips and Painter. If the producer is reporting a potential problem, then an investigation and reporting process is initiated. Animal health companies remain an imperative part of the CSI team.

“The goal is to understand the source of the failure initially by looking at any number of potential causes, including compliance or production issues,” Painter says.

“We start an investigation by collecting history and documenting what was done and observed,” he says. “We assist customers in these investigations, and take any production-related issue seriously at Zoetis to determine why a vaccine is not meeting expectations.”

Waddell notes that by regulation, animal health companies that produce licensed vaccines are required to report any unexpected outcome involving its products.

He says, “For example, if there is an injection reaction or a perceived lack of efficacy, this would be an unexpected outcome of vaccination and should be reported to the company, who will, in turn, report it to the USDA.”

Still, the level of care doesn’t stop at doing what is required by regulation. Each technical veterinarian stresses they want to help the producer to look at the big picture and figure out the reason for an unexpected vaccine performance.

On the animal health level, the lot and serial number are key. The companies can test the leftover product against the lot in the lab because a subset of that lot is preserved.

Painter says, “It’s good for producers or farm personnel to get in the habit of recording serial numbers when documenting vaccination procedures.”

If a vaccine or vaccination protocol is not meeting expectations, then communication with the veterinarian and vaccine company is important to develop an investigation to identify the root of the problem.

Check on procedure

While the company is investigating the vaccine, it is vital to probe into the vaccination procedure itself. According to the veterinarians, often the problem lies in vaccination compliance.

For most hog farms, it takes many hands to raise pigs. Sometimes an animal health technical veterinarian can audit those procedures, but it is recommended that a herd veterinarian always assist hog farmers with that part of the investigation.

The bottom line: A probe into the farm’s vaccination practices can unroot problems that eventually could be costly to an animal’s health and the farm’s profits.

Painter says many factors can contribute to diminished efficacy, and in some cases, it is due to administration or poor planning. Vaccination days must be carefully planned in advance, so the right vaccine in the correct amount is on hand when the day comes. It is also crucial the staff is properly trained.

What not to do

Here are some common errors:

■ not starting with healthy animals, which are sick or potentially immune-compromised

■ missing a pig or group of pigs

■ poor timing of vaccination (For a vaccine to work at an optimal level, it must be administered at least two to three weeks before the animal or group of animals are exposed to the pathogen.)

■ not following label instructions

■ not fully understanding the handling of a live attenuated vaccine vs. killed vaccine, especially regarding syringe care

■ leaving disinfection residue on a syringe (Disinfection can kill a live attenuated vaccine. And the antimicrobial residue in the syringe could interfere with any vaccine.)

■ not using the right needle or right angle of needle during administration (It is important that the vaccine be administered by proper route for the development of optimal immunity.)

■ over- or underdosing

■ not vaccinating the entire group

■ not administrating the second dose if required by label

■ using outdated vaccines

■ not properly preparing a vaccine before administering

■ trying to use leftover vaccines, such as modified live, that have been rehydrated and needs to be used immediately

■ improperly mixing vaccines or other medications like antimicrobials

■ improperly refrigerating vaccines in storage or not maintaining proper temperature during shipping

Philips and Waddell also advise not to overlook other factors that may cause stressful events, such as nutritional issues, environmental factors or coinfections. “Something as simple as drafts can cause enough stress to inhibit or compromise a protective immune response,” Waddell says.

Like humans, all pigs are not created equal. As a hog producer, it is expected if you give the vaccine to 4,000 pigs, you expect an identical response for each pig. However, it is not that simple, Waddell and Philips note.

They say, “The overall goal [or] objective is to appropriately vaccinate groups of pigs to generate a uniform level of immunity across the group or population. In this context, it is important to understand that biologic variation is inherent, and that not all pigs or groups of pigs respond exactly the same. The factors discussed here can affect or cause increased variation in the immune response within a group of pigs. It is important to manage these compromising factors to minimize variation and optimize population immunity.”

Avoiding vaccination failures

For the farm, an immunization program should not be merely purchasing a vaccine and administering it. As one of your management tools, it is imperative to devote time and effort in developing a vaccination strategy that includes comprehensive training for any individual handling or administering vaccines, and full assessment of all potential reasons a vaccination program may fail.

Employee training is key. Painter, Philips and Waddell say training employees starts with explaining “why” the farm vaccinates. On the whole, compliance is an issue, and education helps overcome that. Understanding why you vaccinate pigs, how to properly do it and knowing what outcomes to look for is improved with education and training. Zoetis and Boehringer Ingelheim offer education opportunities for their customers.

Seeing a gap in the understanding at the caregiver level, Zoetis created the Vaccinologist Program. Painter explains the program is administered by local, experienced Zoetis field personnel and consists of three stages.

The goal is to provide caregiver training on the importance and proper administration of vaccines, and is supported with training tools formatted to fit the needs of the farm and caregivers.

The education portion is conducted in a classroom setting, where participants learn basic pig immunology, how vaccines work, and compliance and technique issues, some of which is reinforced through visual and interactive learning.

After the classroom session, caregivers are given hands-on experience to review and organize the vaccine storage and vaccine administration. At the end of the program, caregivers are acknowledged for completing this specialized training.

Whether the farm participates in a formal educational program hosted by an animal health company or its own, the educational process must start with explaining to employees how important their role is to promoting pig health and why vaccination is critical, Painter says.

“What we have found is that caregivers take more pride in their work when they understand the importance of the work they are doing,” he says. “The Vaccinologist Program from Zoetis explains the importance of their role, the reasoning behind vaccinating pigs and what outcomes to look for. We discuss how to handle and administer vaccines effectively and how important this is to the overall health of the pig.

“Knowledge is paramount to getting buy-in from the caregivers. For producers, a trained and engaged workforce supports a profitable, sustainable business,” Painter says.

Infection Chain approach

Boehringer Ingelheim veterinarians use the “Infection Chain” approach as part of a five-step process to aid producers and veterinarians in coordinating and optimizing the use of multiple management tools to effectively meet the challenges of pathogen control in a production system.

Philips outlines this five-step whole-herd approach:

1. It begins with defining the farm’s desired goal and objective to control each pathogen.

2. From there, it is quintessential to understand the Infection Chain, or the current status of pathogens through diagnostic testing. Basically, it is an investigation to understand if a pathogen is present and its pattern of active circulation and transmission by phase of production.

A whole-herd approach to identifying and understanding the current status of a pathogen and its clinical impact is a fundamental part of developing an effective vaccination and management protocol.

3. The next step is to identify the farm’s constraints or the things that impede you from achieving your goals, Philips says. Examples of these constraints could be available labor, lack of biosecurity measures or pig-flow management strategies that may foster chronic or endemic circulation and transmission of pathogens. Once identified, strategies to prioritize and manage these constraints can be implemented.

4. Utilize the data gathered in steps one, two and three to devise and develop a control plan.

5. Implementing the plan and measuring and monitoring its effectiveness is the final step. Monitoring is instrumental in measuring the progress of your protocol and allowing you to adjust the plan as needed, Philips says.

Painter, Waddell and Philips advise not to overlook communicating and educating any vaccination plan to employees. Compliance is deep-rooted in their understanding.

Under relentless review

A comprehensive vaccination program for each farm has many benefits. “As consumers are becoming more concerned about antibiotic usage, one of the effective ways to reduce the need for antibiotics in the swine industry is to use an effective vaccination program,” Painter says.

Robust vaccination programs should be reviewed routinely to remain effective. Painter, Philips and Waddell urge an annual discussion with a veterinarian. The pathogen or disease status can change.

A habit of conducting diagnostic testing to monitor the status of pathogens and view herd health status, along with a routine discussion with the herd’s veterinarian, can reap the biggest return for the producer.

It is a best management practice to dedicate time each year to review your farm’s vaccination program and not wait to make decisions when faced with an animal health crisis, Painter says.

While the farm may be experiencing a couple of years of excellent herd health status and performance, now is not the time to let the guard down or cut back. Emerging animal diseases lurk around every corner, and keeping animals at their peak health is a solid defense move.

At times of high herd health, it may be tempting to stop vaccinating. Before producers take that step, it is recommended they have a discussion with the herd’s veterinarian and review the farm’s animal health plan.

Don’t let down your guard

Typically, it is never a good idea to stop vaccinating for a disease just because the farm is experiencing an exceptional animal health year.

“If we look at the health of the herd, it’s much more economical to prevent disease than it is to treat it. So, if you have a disease that’s preventable and a vaccine to use to prevent it, that is your best option,” Painter says.

In the past, swine producers did try this for porcine circovirus. Painter recalls a time when the vaccine performance for circovirus was phenomenal, and there was a temptation to stop vaccinating for the disease. He says many did stop vaccinating for it, and it failed miserably.

“That also sticks in my mind whether you continue to vaccinate or not,” he says.

In summary, a solid vaccination program is wise for the health of pigs and the farm’s economic bottom line.

At a minimum, a concrete program incorporates these practices:

■ understanding the current herd health status

■ noting the timing of vaccines

■ offering full employee education and a training program

■ implementing a written plan for employees to follow and schedule

■ monitoring and adjusting the plan as needed

“It provides a solid foundation for reducing the need for antibiotics by preventing or minimizing diseases and illnesses in pigs. As consumers continue to scrutinize antibiotic use in pigs, producers need to ensure they maintain disease prevention efforts,” Painter says.

“Of course, the healthier pigs create increased profitability for producers, so the economic impact of not vaccinating should also be a key consideration,” he adds.

More tools to use

Still, Waddell and Philips note an optimum vaccination strategy is just one tool in the animal health management toolbox. They advise not to overlook the complementary components, such as good biosecurity measures, a balanced nutritional program, a healthy environment and good pig flow management.

“Besides the direct benefit of a vaccine program — reduced clinical signs, improved average daily gain, improved health performance and reduced treatment — for some diseases, the indirect benefits of a population-based vaccination program and vaccine-derived immunity can be a reduction in the level and transmission of pathogens within and between vaccinated populations,” Waddell says.

“You tamp down the disease cloud coming out by having a uniform, standardized immunity across that herd.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like