Suckling intensity may impact weaning-to-estrus intervals

There are many things during lactation that can affect weaning-to-estrus intervals including feed intake, loss of body condition and season. However, if these things appear to be managed well in a herd and there still are problems, then it may be worth evaluating how many and when piglets die during lactation.

Lactation is good for both piglets and sows. Piglets are provided with passive immunity and their main source of nourishment by consuming colostrum and milk, respectively, and the reproductive systems of sows are given a chance to recover before being asked to resume their normal reproductive function.

The latter is provided by the sucking activity of the litter. There are nerves that run directly from the nipples to the areas of the brain that control the release of the gonadotropins, LH and FSH. When these nerves are stimulated by piglets nursing signals are transmitted directly to the brain and secretion of LH and FSH are kept at very low levels. During the early stages of lactation this is fine because follicular growth during this period of time is low and doesn’t require much LH or FSH. It also is good for what happens later because the brain needs to synthesize and store increased amounts of LH and FSH in order to support the very rapid period of follicular growth that occurs after weaning.

If this doesn’t happen, then delayed weaning-to-estrus intervals or even anestrus can occur. Consequently, establishment of this suckling-induced inhibition of LH and FSH secretion early in lactation is important for a normal weaning-to-estrus period and probably is one reason why there appears to be a positive correlation between the number of piglets that sows nurse at the beginning of lactation and their subsequent reproductive performance — hence, the common recommendation of “loading sows up with pigs,” especially first parity sows.

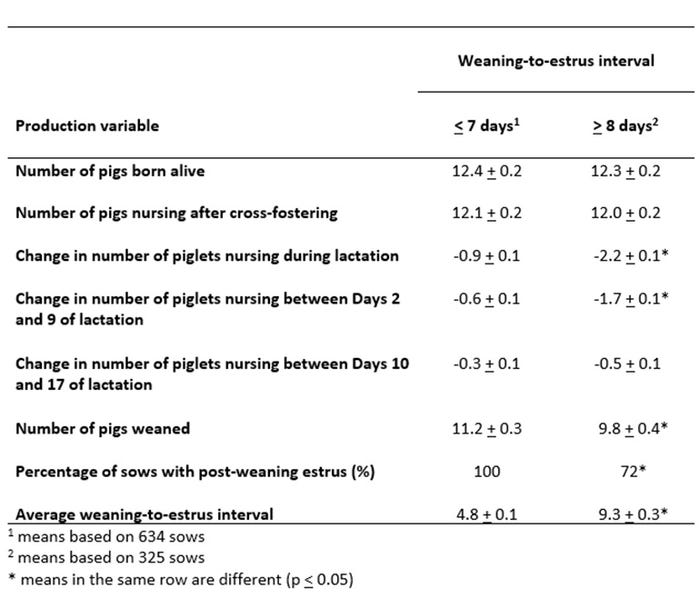

In a recent study, changes in the number of pigs nursing during each week of lactation were examined in relation to subsequent weaning-to-estrus intervals. On the farm from which these data were collected cross-fostering was done exclusively during the first 48 hours after farrowing unless there was a situation in which a sow died or stopped producing milk in which case piglets were fostered onto other sows as needed. As a result, most of the changes in number of pigs nursing were due to pigs dying for various reasons, i.e. — being mashed; low viability, etc. Results from this study are shown in Table 1 and clearly indicate that, on this particular farm, the reduction of piglets during the first week of lactation after cross-fostering had a profound effect on the subsequent estrous activity of sows after weaning. Those that had a normal weaning-to-estrus interval lost about three times fewer piglets during the week after cross-fostering and about 50% fewer piglets overall during lactation compared with their counterparts that had delayed estrous activity or failed to return to estrus after weaning.

Table 1: Relationship between number of pigs nursing during each week of lactation and subsequent reproductive performance of sows.

One way to think about this from a physiological perspective is to compare it with a “leaky faucet.” The suckling-induced inhibition of gonadotropins in the group of sows that had low piglet losses was most likely established quickly and remained intact. This allowed the brain to synthesize and store both LH and FSH very effectively so that there were adequate levels present after weaning to support the rapid period of follicular growth.

Consequently, this group returned to estrus quickly and efficiently after weaning. In contrast, in the group that experienced the high piglet losses, this didn’t happen as effectively or as efficiently since there was a reduction in suckling intensity. In other words, the suckling-induced inhibition was not as strong so it is possible that LH and FSH “leaked out” of the storage areas in the brain and adequate amounts were not present prior to weaning. As a result, it took longer for follicles to reach preovulatory size so both estrus and ovulation were delayed, if they occurred at all.

There are many things during lactation that can affect weaning-to-estrus intervals including feed intake, loss of body condition and season. However, if these things appear to be managed well in a herd and there still are problems, then it may be worth evaluating how many and when piglets die during lactation.

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like