Each farm needs right vaccination program for pigs and profits

Individual management styles and system-specific disease profiles and pig flows will influence how producers manage their farm’s vaccination program.

February 6, 2018

Time is money, and vaccinations can be a necessary but costly tool in a producer’s toolbox. It is imperative that producers get the most value from the vaccines they choose to use, and from their employees’ time spent administering them.

The Pork Quality Assurance Plus Education Handbook, something producers should be familiar with, devotes a “Good Production Practice” section on the proper use of animal health products, including vaccines.

Paul Ruen, a veterinarian at the Fairmont Veterinary Clinic LLP in Fairmont, Minn., says, “PQA does a good job of laying out the how-to of proper techniques and safety concerns relating to the use of injectable and oral delivery products, but it doesn’t speak to the decision process and strategies for managing health across a wide range of production situations.”

Individual management styles and system-specific disease profiles and pig flows will influence how producers manage their farm’s vaccination program.

“Trying to balance the cost-benefit of vaccine and other inputs is difficult. Commercial farms are not designed for research, so sometimes it’s hard to draw conclusions from their use. In the most basic sense, vaccines are simply disease and economic risk management tools,” Ruen says. “So clinical impressions, production data and financial information should all be used to assess success. Although most farms aren’t in the business of vaccine research, you are trying to get the best results for your herd.”

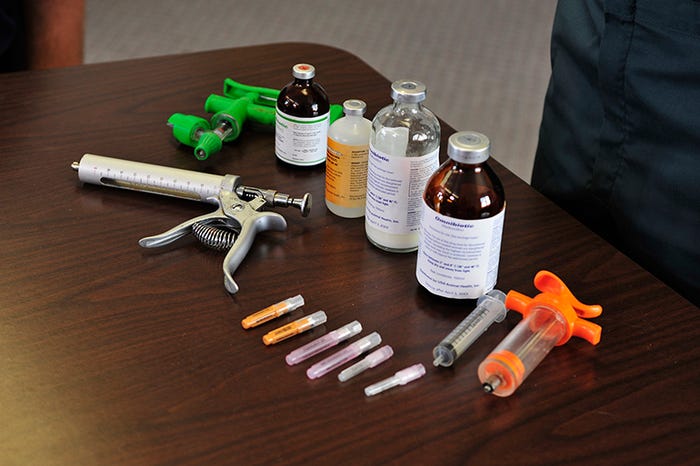

Maintenance and storage

Proper cleaning, maintenance and storage of all equipment used for administering injections will ensure the correct dose is given to each pig and that contamination of a product is prevented. Some keys steps for proper syringe management include:

• Properly discard disposable syringes immediately after use.

• Rinse out reusable syringes with hot water. Do not use soap or other disinfects on the inside of any syringe.

• Wipe down the exterior of syringes with water and mild soap to remove any dirt or debris.

• Store syringes in a clean area or box, and allow them to dry between uses.

• Periodically lubricate and replace parts as needed.

• Periodically check the calibration of reusable syringes for accurate dosing of medications and vaccinations.

• Clean the vial’s rubber stoppers before inserting a needle.

• Use only clean needles to withdraw contents from multi-dose vials.

Source: PQA Plus Education Handbook

Ruen says the industry’s evolution has driven a change in the philosophy of how to manage farms and their vaccination programs. “Over a long period of time, we’ve seen the industry go from farrow-to-finish to multisite production to two-site production. And so it’s wise to take a step back and ask should we be making the same decisions as we did before.”

In the breeding herd, for instance, farms today purchase gilts much younger — at 3 to 10 weeks of age.

“The extra acclimation time can benefit herd health stability, guarantee a steady flow of replacements into the farm, and put the care of these animals in the hands of the same people who will be managing them throughout their productive breeding life,” Ruen says. “Having more time to raise them in the herd conditions — facilities, feed and health environment — is having a positive long-term impact on productivity and performance of their offspring.

“Communication must be very good between phases of production so that the handoff of the isowean pig to the wean-finish phase is smooth,” he says.

Ruen sees some producers wishing to get the most injectable vaccine into the piglets while still on the sow, but that needs to be balanced with adequate protection all the way to market. Sometimes challenges downstream demand that pigs are vaccinated older.

Companies that manufacture vaccines and biologics cannot possibly test their products in a challenge model under all the unique profiles on pig age, vaccine timing and herd disease that exist in the industry. But often they will work with the producer and veterinarian to investigate best practices for a farm or flow of pigs.

“We always appreciate their insights and technical support for investigations and trials,” Ruen says.

Broken-needle SOPs

From the Pork Checkoff’s needle management campaign — One Is Too Many — here are standard operating procedures to consider in preventing broken needles.

1. Use the right needle

Consider:

• needle strength

• detectability

• needle length and gauge

• animal’s size

• injection site

• medication’s characteristics

2. Use the needle right

• Ensure proper animal restraint.

• Identify the proper site for injection.

• Change the needle:

° if it is bent or damaged (Never straighten a bent needle.)

° to maintain its cleanliness and sharpness

° between pens or animals, as recommended by your veterinarian for that type of needle, animal or medication

• Monitor needle usage and account for all needles after use:

° Consider a needle inventory management system.

° Retrieve dropped needles.

° If a needle breaks in an animal, identify the animal immediately and attempt to recover the needle.

° Store new needles and dispose of used needles in the appropriate manner.

Realizing there is no one-size-fits-all regimen for all operations, Ruen says producers need to look at the flow of the pigs under their care. “Understand the historical challenges the farm has faced, and anticipate based on the neighborhood, genetics, feed and other management factors. Partnering with a high-quality diagnostic laboratory helps monitor health of pig flows in my practice. Some of the diseases we discuss and may plan for include PRRS, SIV, Lawsonia, salmonella, mycoplasma, PCV2 and erysipelas. Some others that can be factors are E. coli, H. parasuis, A. suis and strep.”

Ruen adds, “Some combination of vaccine [injectable, oral, intranasal] or strategic medication may be part of the plan. Routine diagnostics help us assess where our plan is working and, also, when it needs adjustment. Vaccine plans work best when tailored to the unique needs of the farm’s management and pig flow. Disease profiles will change over time, and so too must our strategies. Bottom line: The pig will tell you much of what you need to know.”

Ruen says work from the 1980s and ’90s showed that when you stimulate the immune system, it takes energy from the pig to respond, “and it appears that immune stimulation can pull away energy that could have been used in other ways by the pig, such as for growth, and that it doesn’t matter if it’s response to disease or a response to vaccine. So you need to have a good reason for using that vaccine, or else your risk management may be costing you productivity.”

Timing is everything, and Ruen says that attention needs to be paid to the impact of active disease, maternal immunity and animal stress. We expect that sick pigs don’t respond as well to vaccination as healthy pigs.

Whether it’s because the immune system is tied up with more pressing problems than what you just injected, or that sick animals don’t go to the water trough to drink that oral dose of vaccine, we aren’t giving the pig the best opportunity to achieve protection, Ruen says. In the case of the breeding gilt, we know that maternal antibody to parvovirus can interfere with active immunization if gilts are vaccinated too young. Other procedures or environmental stressors can impact the quality of the immune response as well.

And from a practical standpoint, “you want the animals to like you, to be comfortable around the farm staff, so any negative stressor around the time of breeding can be detrimental to productivity,” Ruen says. “We want to be done with all vaccinations, tattooing, etc. … for at least several weeks before we intend to breed. Husbandry has a big impact.”

Producers have options to limit the stress of injectable vaccines, such as using combination vaccines or single-dose products. Oral vaccines given via the water system save labor and eliminate vaccination stress entirely. Those live avirulent oral vaccines require regimented handling and avoidance of antibiotics during the window, as well as before, during and after administration.

Ruen says adding dye to the vaccination in the water system is a quality control measure that gives the caretaker the ability to know it’s being administered correctly throughout the barn and to all the pigs.

As many vaccines that are available, and the number of different farm management techniques, there are also a great number of vaccination strategies that producers need to weigh what works best: multi-dose products, two doses prewean, one dose prewean, one dose post-wean, two-dose post-wean. Ruen says it is important to adhere to label directions for the vaccines used — not only when applying, but also in monitoring the necessary withdrawal period.

“The changes thrust upon food animal production due to the veterinary feed directive in 2017 did generate some important discussion and review of health management plans on farms,” Ruen says.

Over the past five to 10 years, more focus has been placed on herd health upgrades with depop and repop, disease elimination, and strategic vaccinations to maintain and improve pig performance and economics.

A vaccination program is an essential part of any producer’s toolbox to maintain herd health, but it’s a tool to use wisely. “It’s got to be safe and easy to accomplish for people, it’s got to be effective in the pig, and it’s got to be the right cost-benefit for the producer,” he says. “So it’s a team decision.”

Being that every team is different, here are Ruen’s take-aways that will fit every system: “Just keep your eyes open. Daily observe the pigs and the people,” he says. “It’s got to be financially data-driven. It’s got to be less stressful for the animal. It’s got to be safe and easy to do. … Ultimately, keep an eye on the pigs. The pig is in charge. They will tell you what they need.”

Types of injections

Intramuscular: in the muscle

Subcutaneous: under the skin

Intraperitoneal: in the abdominal cavity

Intravenous: in the vein

Intranasal: in the nasal passages

Injection either by intraperitoneal or intravenous should be used only upon veterinary instruction and guidance, as serious injury, including death of the pig, can occur.

Source: PQA Plus Education Handbook

You May Also Like