Why do we keep getting it wrong when it comes to biosecurity?

People, facilities and pathogens need to be considered on a broader scale.

"Biosecurity is expensive. If I spend everything on biosecurity, I will lose my business. If I spend nothing on biosecurity, I will lose my business."

That pork producer’s concerns are words that have stuck with Dr. Paul Yeske and the Swine Vet Center team. And after nine years practicing swine veterinary medicine, team member Jordan Graham says the industry needs to find some middle ground.

“It seems when we talk about biosecurity, we often talk about the same items over and over again,” Graham says. “And we don't always look at the bigger picture and say, ‘what are things we are doing as production teams, as veterinarians, that are impacting execution of biosecurity?’”

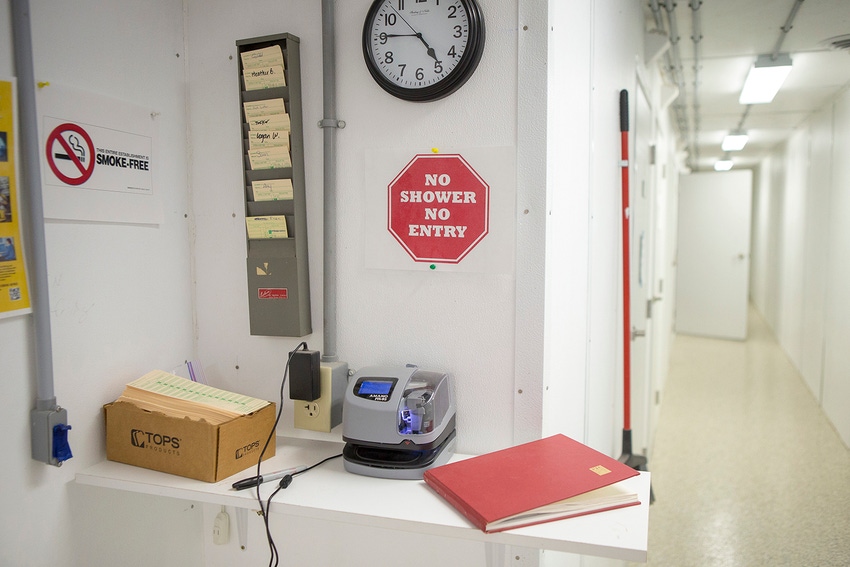

Headquartered out of St. Peter, Minnesota, Swine Vet Center is in the heart of hog-dense country and the veterinarians deal with biosecurity issues regularly. While clean/dirty lines, transport sanitation, shower in/out, downtime, pest control and mortality removal protocols are regularly communicated to production teams, Graham says these standard operating procedures are often done incorrectly. From unclear clean/dirty lines and manure covered tools entering the UV chamber to the rendering box being placed next to the barn and office pets tracking through facilities, Graham says as an industry we often get it wrong when it comes to biocontainment. His focus now is figuring out what is making it so hard for producers and staff to execute their SOPs.

“What I've found is one of the biggest challenges revolves around timing,” Graham says.

For example, vaccinations, loading in and out, site closeout/washing and mass treatment are all timely and also all have one thing in common — people. However, the demographics have changed in contract finishing.

Twenty years ago, there may have been the site owner/caretaker or second-generation contract holder conducting chores on the sites they owned. They handled all the load outs and power washings, the vaccinations and mass treatments, and problems were often “just a call away.” Contract finishing facilities have now become more of an asset on the balance sheet to a farming operation, in terms of manure and equity, rather than a revenue stream, Graham notes.

The veterinarian also sees a lack of interest from the next generation.

“My generation, the millennials, are more interested in GPS systems, equipment, and agronomic technology versus taking care of hogs every day,” Graham says. “So, that translates into what it looks like today. The majority of labor is contracted or hired.”

That staff typically chores multiple sites and sometimes over multiple systems. Many pork production systems have separate crews for loading in/out, power washing, vaccinating and mass treating. Also, there is often a language barrier between managers and staff.

What can veterinarians and producers do better? Graham says the big thing is “know your labor.”

“Understand where they're going day to day, what their responsibilities are and what their ability is to get the job done,” Graham says.

He also strongly advises making site specific equipment a priority. “Buying equipment for each site is expensive, but you will pay for it in health breaks through disease transmission.”

Also, the veterinarian says downtime needs to be defined. What does one night down mean for the production team?

“For many contract labor crews, there is no nighttime. It's loading out at 2:00 in the morning, receiving wean pigs at 6:00 in the morning, and it's the same people completing each job,” Graham says. “So, if that is the case, we really need to be communicating with that site caretaker to make sure that we're adhering to biosecurity expectations.”

When it comes to keeping disease within a herd, pigs, people, and facilities all influence biocontainment. While showering in and out, site-specific clothing/equipment and downtime are critical, Graham says the facility itself may have a broader impact than previously considered.

The expansion of the swine industry in the 1990s and early 2000s saw many new sow farms built in pig-dense areas. These farms had access to corn, land for manure application, and minimal transport to finishing/processing. However, this was the same time porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome virus was spreading throughout North America, Graham notes.

“The big thing that these facilities lack is isolation and onsite gilt development. Now, many facilities have added both isolation and onsite gilt development,” Graham says. “None of them were built filtered. We've retrofitted filtration in many, but there are still many sow farms in dense areas that are not filtered that also lack setback from other swine facilities.”

So, what should producers and veterinarians do to help manage biosecurity on these close-knit sites? Graham advocates for onsite gilt development, which often brings rebuttal from clients, noting that purchasing mature gilts is more cost effective than raising them on site.

“Managing those gilts on site requires a new labor set. Additionally, acquiring the capital needed to add to these facilities is difficult for lenders considering we don't wean more pigs,” Graham says. “The throughput doesn't change on paper, however, in the bigger picture, it's something we can help to bring this message across … these disease outbreaks are happening more frequently on farms where previously we were able to get 18 months between breaks, 9 to 10 months between breaks is very common.”

Many farms have moved towards exposing gilts to resident pathogens to maintain health stability. In Graham’s practice area, on farms where filtration or elevated biosecurity measures are not possible, it’s common to maintain stability versus eliminate disease. The disruption of herd parity and throughput outweighs the benefits of disease elimination when time between health events is a year or less.

However, not having onsite gilt development and ongoing pathogen exposure has resulted in extended time to low prevalence, with resident pathogens never being eliminated and area disease prevalence increasing in nursery grow-finish sites.

Graham says the industry has an “evolving understanding of PRRSv.” Multiple viruses within an animal or herd, as they're replicating, can undergo genetic recombination between each other, creating a novel virus to the herd.

“As a veterinary profession, we must continue to push towards farms that are able to eliminate pathogens and maintain production. And we have to be able to convey the benefits of setting systems up to do so without the expectation of a short term increase in weaned pig output,” Graham says. “Because in reality, if we don't come to a position where we can eliminate diseases within an area, we could create a spiral of virus recombination.”

Bioexclusion and biocontainment also need to be considered on a broader scale, Graham says.

“Think of the people, how are we setting our people up to execute biosecurity correctly versus saying, ‘well, they’re not doing the job right.’ Do they have all the tools to do it right?” Graham says. “How are our facilities set up that it makes it hard for people to get biosecurity done right? And we have to remember, particularly PRRSV, and how our decisions to maintain stability by continuing to expose might be creating more problems for us down the road.”

About the Author(s)

You May Also Like