Influencing the gut motility of gestating sows

Sows fed soluble fiber from sugar beet pulp have increased fecal water holding, binding capacity compared to sows fed insoluble fiber from corn DDGS.

March 30, 2023

It has been widely shown in the United States that including fibrous co-products in gestation diets can impact animal welfare, weight management and satiety. However, in the European Union, where there is a minimum fiber level in all gestating sow diets, they have recognized improvements in gastrointestinal physiology, longevity and farrowing efficiency. These improvements are noticed in the presence of predominately soluble fiber sources, such as co-products from the EU's small grain and root vegetable industries.

Dietary fiber has been categorized as soluble or insoluble due to analytical methodology. It is commonly inferred that soluble fiber is more fermentable; however, solubility does not always mean fermentability. For example, pea hulls are an insoluble fiber source that is highly fermentable. This is because solubility is a chemical characteristic related to its interplay in water rather than a physical property of the feedstuff.

Looking past solubility and classifying fibrous co-products based on their composition of non-starch polysaccharides can give us more insight into their physicochemical and physiological properties with the gut. For example, the NSP content of hulled oats and barley has a large concentration of glucans. In contrast, corn DDGS and wheat middlings are largely arabinoxylan-based, and sugar beet pulp is predominately composed of cellulose and pectin. It has been demonstrated that water plays a pivotal role in the physiological properties of dietary fiber in the GI tract. Each NSP has a unique interaction with water and subsequent influence on gut physiology.

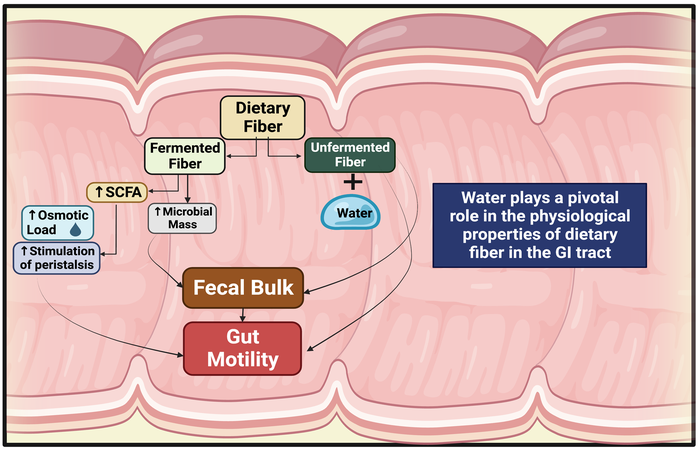

The synergistic relationship between the fermentability of dietary fiber and water in the gastrointestinal tract is crucial in understanding how dietary fiber will influence gut motility and, thus, satiety and constipation within the sow (Figure 1). Fermentable and unfermentable fiber work in different ways, contributing to fecal bulk and gut motility. More fermentable fiber, like SBP, has a chemical attraction to water through cation-anion exchange and hydrogen bonding, holding onto that water as it passes through the GI. Fiber fermentation increases microbial mass, contributing to fecal bulk and short-chain fatty acid production, which alters osmotic load and stimulation of peristalsis, contributing to gut motility. In contrast, corn DDGS has a physical attraction to the water where it sits in the pores of the fiber contributing to fecal bulk through bulk density and gut motility by an increased passage rate. The impact of gut motility on constipation is crucial, especially in the late transition period before farrowing.

The role of dietary fiber and its contribution to fecal bulk and gut motility

Our experimental objective was to investigate the effects of both insoluble and soluble fiber on water balance, fecal physicochemical properties, electrolyte balance and markers of gut motility in mid and late-gestating sows. This study focused on including two different dietary fiber sources contributing to other physicochemical properties. We used 36 PIC Camborough sows at parity 3 ± 0.73 assigned to treatment at d 28 of gestation to a diet with 20% corn DDGS or 20% SBP formulated to meet or exceed PIC recommendations. The sows underwent two metabolism collections at mid (d 50-59) and late (d 99-108) gestation. Plasma and fresh fecal samples were collected on d 0, and a complete water balance study took place from d 4-8, where intake, wastage and output were recorded.

We found that sows fed SBP had increased water binding capacity (WBC) by 76.6% compared to sows fed corn DDGS, respectively (Figure 2). Additionally, sows fed SBP had increased water holding capacity (WHC) compared to sows fed corn DDGS by 36.9%, respectively. This can be explained by the NSP composition of SBP and its interplay with water as a fermentable fiber outlined previously. Similar results were recognized in late gestation due to decreased transit time and the crowding of reproductive organs on the GI. We also observe a repartitioning-like effect of the water from urine to feces in sows fed SBP, believed to be attributed to the fecal physicochemical properties above (Figure 3).

Markers of gut motility were influenced by the difference in dietary fiber sources as well. There was a tendency for plasma CCK to be 28% greater in sows fed SBP in alignment with human nutrition studies of soluble fiber creating viscous gels. While there was no effect of dietary fiber on PYY, a period effect was observed where it was decreased by 17.5% in late gestation, likely due to delayed gastric emptying.

This study demonstrated that feeding sows soluble fiber repartitions water to feces, reducing urine output and altering fecal hydration characteristics. Also, markers of gut motility are specific to dietary fiber type in relation to the point in gestation due to the physiological changes in the gastrointestinal tract.

In conclusion, water should not be the "forgotten nutrient" due to its dynamic interplay with fiber in the GI, influencing the physicochemical properties of digesta. This relationship between water and the physicochemical properties of soluble fiber may help explain the alleviation of constipation in sows fed with high levels of dietary fiber. The inclusion of soluble fiber in late gestating sow diets shows the potential to stimulate gut motility, ultimately reducing constipation which could influence farrowing performance metrics positively.

You May Also Like